“This device isn’t a spaceship. It’s a time machine. It goes backwards and forwards. It takes us to a place where we ache to go again. It’s not called ‘The Wheel.’ It’s called ‘The Carousel.’ It lets us travel the way a child travels: around and around and back home again, to a place we know we are loved.”

—Don Draper, talking about the nostalgia of a slide projector carousel, “Mad Men”

Tracking Shots

This is a story whose chronology begins with Larry Hagman‘s wounded chest, and ends with David Caruso‘s naked behind. But the best place to start is in the middle, with a late-night car ride down to the docks.

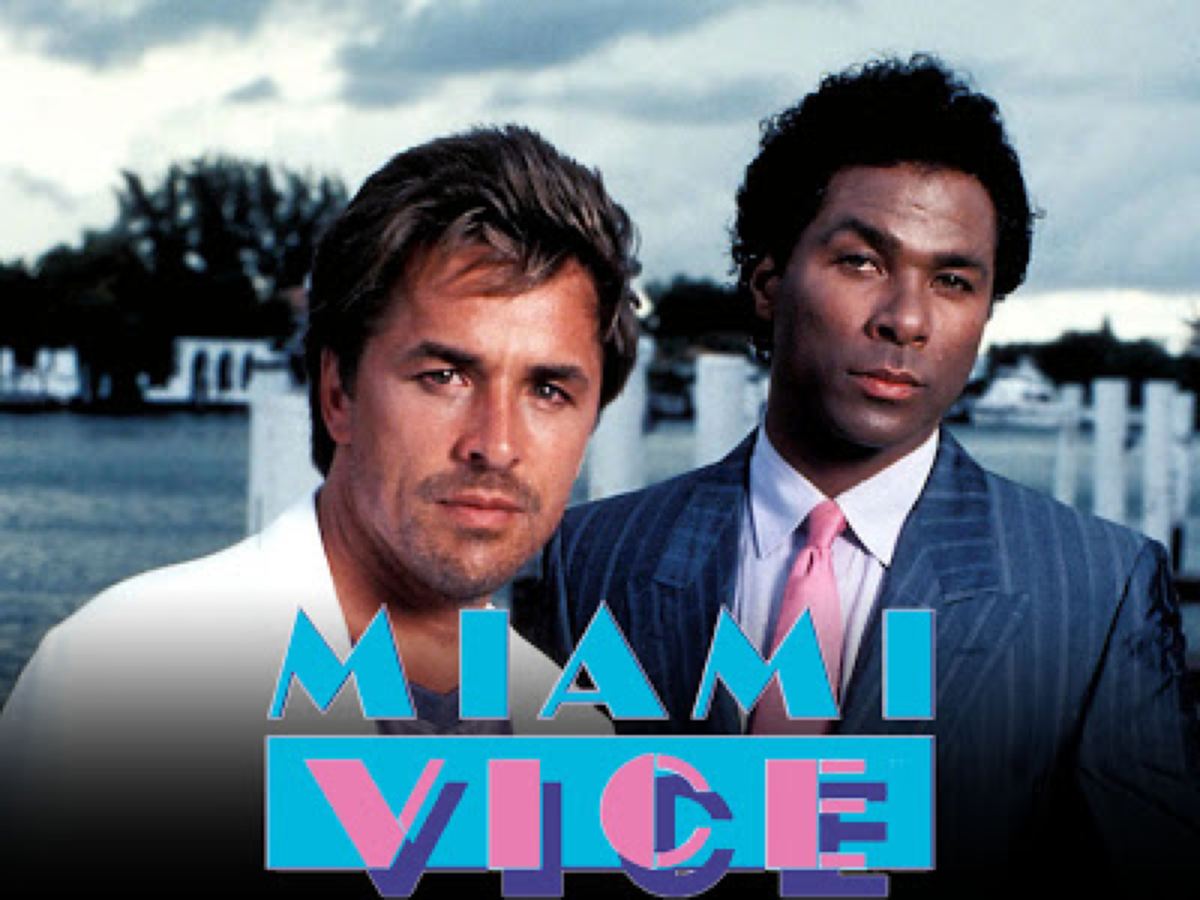

The scene starts with a close-up on the reflective black front of Sonny Crockett’s Ferrari Daytona Spyder as it zooms down the Miami streets; the wide-angle lens causes the headlight, bumper and hub to jut forward and slightly right, creating an almost 3-D effect that emphasizes the vehicle’s shark-like, predatory shape. We have time to notice the bright orange headlights, the ornate hubcaps, the white dots spinning off the hood as it passes beneath streetlights, because this shot—set to Phil Collins’ “In The Air Tonight”—is fifteen seconds long. That’s an eternity in television even now, but especially so when this scene aired as the centerpiece of the “Miami Vice” pilot in 1984.

It’s followed by another fifteen-second shot, a medium framing of Crockett and his partner Tubbs in the front seats; neither speak as the wind blows their hair, their only communication a pensive glance from Tubbs to Sonny (who looks straight ahead, not acknowledging it). There’s another cut to the Spyder’s rear tire, seen spinning in profile for eleven seconds, before another cut returns to the men in the front, as the sound of Tubbs loading his gun blends with the steady rhythms of Collins’ synthesizers. A reverse shot places Tubbs in the foreground as Crockett finally speaks: “How much time we got?,” he asks.

He’s referring to the coming showdown with their drug-lord antagonist, but he might be commenting on the scene’s construction, as writer Anthony Yerkovich, director Thomas Carter, and showrunner Michael Mann induce a temporal vertigo: even though Crockett and Tubbs are racing to a meeting, our senses are slowed by all this visual lingering, and the way the long takes interact with the metronomic rhythms of Collins’ song.

The legend of “Miami Vice” states that NBC production chief Brandon Tartikoff wrote “MTV Cops” on a napkin, and the show would come to be known as much for its use of pop songs, music video editing, and sensuous colors as its characters or plots. But this scene feels emblematic of “Vice”‘s five-year run precisely because it’s less MTV than Antonioni with a drum machine: slow, opaque, with the viewer dropped in medias res to a moment where spatial exploration feels as important as story.

Close-Ups

Two recent books on contemporary television, Alan Sepinwall’s “The Revolution Was Televised” and Brett Martin’s “Difficult Men,” posit that the last fifteen years represent television’s “Third Golden Age.” Martin compares it to the flowering of the Victorian serialized novel (“a vast canvas, intertwining story lines, twists and turns and backtracks in character’s progress…equipped not only to fulfill commercial demands, but also to address the big issues of a decadent empire: violence, sexuality, addiction, family, class.”), while Sepinwall sees it taking a role once played by the movies (“If you wanted thoughtful drama for adults, you didn’t go to the multiplex; you went to your living room couch”). Martin focuses on six recent cable dramas about male antiheroes (“The Wire,” “The Sopranos,” “Mad Men,” “Breaking Bad,” “Deadwood,” and “The Shield”); Sepinwall includes broadcast programs like “Buffy The Vampire Slayer,” “24” and “Friday Night Lights,” and a broader variety of genres.

Both ignore sitcoms in favor of dramas. And they agree on many of the reasons for this shift: the expansion of cable in the 80s and 90s and the loosening of FCC guidelines on network ownership, which created a need for programming and splintered the audience into demographics rather than a “big tent” of viewers; the opportunities this created for two generations of frustrated creators to attempt new ideas, leading to “the ascendency of the all-powerful writer-showrunner”; and new technologies and distribution mechanisms (widescreen televisions, DVRs, Netflix, streaming), which encouraged a more “cinematic” look for shows, and denser mythologies primed for perpetual re-viewing by devoted fans.

“Difficult Men” is primarily structured around production histories of the six programs it discusses; “Revolution” also draws on in-depth interviews, but Sepinwall is looking at the period as a TV critic, offering opinions, insights, and wonderful personal anecdotes (the best parts of “Revolution” are those which feel like a coded autobiography crying out for expansion). Both books are intelligent and addictive, and I’m grateful for what they taught me. At the same time, they are jammed with as many contradictory impulses as the shows they cover: it’s perhaps not a coincidence that so many of the programs under discussion are about generating new identities out of (or in deep contrast to) old ones, or how communities and their mythologies are crafted and protected.

“You have to kill the father,” Martin quotes one writer as saying of “Deadwood” creator David Milch, and just as the Milch/Chase generation was working in TV in an Oedipal relationship with cinema, so too do “Difficult Men” and “Revolution,” for all their knowledge and rigor, sometimes feel like they are in an Oedipal struggle with what Martin marks as “The Second Golden Age of TV” of the 1980s. They note the importance of that earlier period, but seem eager to mark off 1997-2012 as Something Different. As an alternative history, let’s take Don Draper’s metaphor of the Time Machine and apply it to television, riding “The Carousel” backwards and forwards between the Third Age and the Second (marked here as lasting between 1978 and 1993). Dropped in medias res into a slowed-down, sensual history, what details might emerge?

Wide Angles

“How much time we got?” For viewers in 1980, the answer was probably “too much,” as the cliffhanger structure of evening soap operas, a holdout by star Larry Hagman, and a Screen Actors’ Guild strike which began in July conspired to keep the answer to “Who Shot J.R.?” from being answered until “Dallas” finally returned in November. There were no DVDs, relatively few VCRs, and no Internet on which to parse the position of J.R.’s bullet wounds, but the long delay created a fan frenzy that spread across magazines, television news, and Las Vegas betting boards.

Jeffrey S. Miller, in his study of British television of the 1960s and ’70s, “Something Different,” posits “Dallas” as the final stage in a decade-long American assimilation of British television shows like “Till Death Do Us Part” (which became “All In the Family”) and the novelistic “Upstairs Downstairs” (which inspired American miniseries like “Roots” and “Rich Man, Poor Man”). But while “Dallas” began in 1978 as a five-episode miniseries (combining “Romeo and Juliet” with the oil-drenched decadence of “Giant”) its final shape as a continuing series, Miller notes, meant “that the closure of a final episode, central to the [miniseries] form, was gone.”

It’s easy to dismiss Southfork 35 years later, but looking back at it during its “Who Shot J.R.?” height, it is “Dallas,” as much as the more-cited “Hill Street Blues,” which feels like the dawn of the Second Golden Age of Television. It is a sprawling narrative that centers on one diverse community, and especially the complex emotional ties and hatreds of two families; it is Dickensian in its rich cast of characters, and its constant ability to call back across many seasons for plot points and satisfying twists; its willingness to incorporate current events into its narratives marks it as a pulpy time capsule of economic and political retrenchment; and most of all, its gleeful celebration of the selfish, contradictory, endlessly insecure anti-hero J.R. is a model for everyone from Tony Soprano to Walter White. As if predicting both the disliked finales of many Third Age programs and the necessity of an open and unresolved story, “Dallas” faltered only when it brought a final moral judgment down on J.R. in its last episode; it would have been far better to continue that tension between love and hate for him that powered its best years, and allowed fans to debate for months who shot the bastard.

Long Shots

I began the exploration of the Second Age with “Miami Vice” and “Dallas,” in part because their respective strengths of visual detail and narrative density highlight the two poles of both the Second and Third Golden Ages, but also because they are almost alone among my examples in being long-term successes: one marker of the Second Age’s most interesting programs is that most lasted only a handful of years before creative differences, ballooning budgets, cultural apathy or network neglect led to their cancellation.

By the mid-80s, writers, producers and directors were pushing envelopes of style and cultural reference in a manner unthinkable a decade earlier, but the longer seasons, standards & practices rules, and the demands of “big tent” ratings made it difficult to sustain these experiments. In essence, these were “cable”-style shows on broadcast networks still uncertain of how to address a changing landscape. None of those commercial failures was shorter, or more depressing, than “Frank’s Place.”

Because so many of the histories of television “landmarks” center on dramas, the role of sitcoms is sometimes overlooked (’70s breakthroughs like “M*A*S*H” or “All In The Family,” or impossible-to-ignore hits like “Cosby,” “Seinfeld,” or “The Simpsons” excepted). So, when the history of MTM productions is mentioned, Steven Bochco’s place is secure. But what about Hugh Wilson’s?

One of the more alarming passages in Martin’s book is his description of “the melancholic credit sequences of the 1970s and 1980s…that promised more depth than their shows ever delivered,” and his inclusion in that bunch of Wilson’s “WKRP In Cincinnati.” It’s an offhand dismissal of a show that, in its own way, was as much a precursor to Third Age workplace comedies like “The Office” as any other sitcom MTM produced. Running between 1978 and 1982, its sometimes awkward blend of the two dominant sitcom modes of its period—”Very Special” social problem narratives and outright slapstick—was just the window dressing for character studies that deepened beautifully over its run.

Wilson’s gift was exploring the surprising humanity underneath the stock types that had populated much of the form’s history, and generating a keen sense of place. The result was a set of melancholy short stories in the guise of a mainstream comedy.

These skills would serve Wilson well when he and “WKRP” star Tim Reid created “Frank’s Place” for CBS five years later. Set in New Orleans, the show centered on Frank Parrish, a Boston professor who inherits his father’s restaurant in New Orleans, and must navigate cultural differences of race, class, and regionality while getting his bearings in a world (and with the legacy of a distant father) with which he has a love/hate relationship.

It was the little details that resonated: in one of the pilot’s best scenes, Frank pops his head into the restaurant’s kitchen on his first day in town, thanking the cook Big Arthur for lunch: “I guess that’s what they call a real fine Cajun meal!,” the well-intending Frank exclaims. When Arthur gives him a dirty look, throws down his spoon and storms out, another employee explains, “That was Creole, Frank! You have to learn these things!”

Shot in single-camera style (a rarity in 1987) and with no laugh track, the show was a challenging blend of comedy and drama, and a broader range of African-American characters (and details of intra-racial difference) than any other show on American television of the period. The restaurant was based on New Orleans’ Chez Helene, and its longtime chef Austin Leslie was interviewed by People magazine when the program aired, where he suggested its mission statement: “When you find family inside a restaurant, that’s when it’s the best.” Despite critical success and numerous awards, “Frank’s Place” could not find an audience in 1987, lasting only one season. As the Museum of Broadcast Communications notes of the program, “Viewers who expected the usual situation comedy formula were puzzled by the show’s style. Frequent changes in scheduling made it difficult for viewers to find the show. CBS, struggling to improve its standing in the ratings, was not willing to give the show more time in a regular time slot to build an audience.”

Twenty-five years after its cancellation, “Frank’s Place” has still never received a DVD release, or any kind of streaming through Hulu or other services (episodes and clips will occasionally show up in bootlegged form on YouTube, but are quickly pulled down). And yet it’s easy to see the program’s quiet, multi-layered, well-researched exploration of community, class, and race having a huge impact on David Simon: Simon’s “Treme” acknowledged as much when it cast Reid in a cameo during the show’s first season, and when HBO later hosted a benefit for the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts that centered on Wilson’s lost masterpiece.

Point-of-View Shots

“Frank’s Place” offers a key Second Age example of the necessity and danger of institutional memory. Within the narrative, there is a broad set of long-held, passed-down traditions and rituals to which Frank must adapt; in the real world, it was the show’s challenge to tradition that made it a hard-sell in a three-network era (today, it would be in its fourth season on HBO or AMC, and debated on Twitter).

Institutional memory matters for the ongoing Third Golden Age, too. The issue here isn’t one of narrative detail—both Martin’s and Sepinwall’s books are rich with it—but the repetitive frameworks into which those details are forced. If you’ve read Peter Biskind’s “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls” (to which Martin’s structure owes much, and to which he tips his hat towards the end of “Difficult Men”), the shape of this history will feel familiar: economic uncertainty in a long-standing medium, coupled with a creative stagnation bred by years of bureaucratic repetition; creative breakthroughs from unlikely places, which generate new paradigms; and rise-and-fall stories of the creators and companies that benefited from that success, as the changes get assimilated or diluted through hubris or repetition.

Breaking those frameworks—generating new and useful stories—is incredibly difficult. While “Frank’s Place” struggled on CBS, two programs airing back-to-back on ABC had greater success commercially, and in doing so further developed the narrative and stylistic paradigms “Miami Vice” and “Dallas” had suggested.

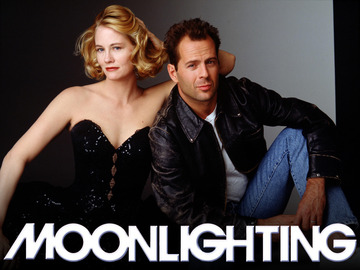

After working at Second City, and writing for “Taxi” and “Remington Steele,” Glenn Gordon Caron was approached by ABC Entertainment chief Lewis Erlicht, who asked him to create a show for the network. In an interview with The New York Times in 1986, Caron recalled the conversation with Erlicht: “I very much wanted to write men and women. ‘What about a romance?’ He said, ‘I don’t care what it is as long as it’s a detective show.’ ”

The program that came out of that conversation, “Moonlighting,” would debut on ABC to mediocre ratings in the spring of 1985. It straddled the romance/detective divide quite competently: its pilot is full of Bruce Willis’ energy, Cybill Shepherd’s dry and very able “straight man” responses, and a mystery plot that’s loose enough for pratfalls and one-liners. It’s sleek and character-driven, but it was when it went to series that it really became something new. In an interview with Rolling Stone a year later, Caron would pinpoint why: “I think it has something to do with the fact that while we may be the fifty-thousandth TV detective show, we know we’re the fifty-thousandth TV detective show. That’s at the heart of it. The show knows a little bit that it’s on TV.”

“Moonlighting” wasn’t the first TV show to break the fourth wall and comment on its own production: sketch comedy had always held that potential, and there was always The Monkees (perhaps not coincidentally, that band would experience a renaissance in 1986, just as “Moonlighting” was making their old methodology new again). But “Moonlighting”‘s ability to provide the emotional investments of a more traditional drama, while still breaking character and offering as dense an intertextuality as any show on TV had to that point, gave it a special frisson that jumped out in the mid-80s. By the fourth episode of the second season, they were staging a black-and-white film noir pastiche (“The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice”) introduced by Orson Welles; by the third season’s “Atomic Shakespeare,” they were making their historical debts explicit by staging “The Taming of The Shrew.” In the dawning home video age, “Moonlighting’ was appointment television because you didn’t know what would happen—or when the fourth-wall breaks, the jokes, the dazzling references that turned back into touching character moments would occur. It was heavily stylized, extremely controlled filmmaking that gave off the “anything goes” pop of live performance.

In that same Times interview from ’86, Caron’s working methods—rewriting scripts until literally the last second, throwing out pages on set, asking for technical detail that caused huge budget overruns—were laid out. They not only suggested the difficulties his own show would soon face, but the complicated working methods of David Milch and Matthew Weiner, as laid out in Martin and Sepinwall’s books. It was, for a brief moment, however, worth it: the show’s creative blossoming was simultaneous with its rise in the ratings, giving hope that taking risks could have massive commercial payoffs.

Certainly, Edward Zwick and Marshall Herskovitz were the beneficiaries of “Moonlighting”‘s success: it’s hard to imagine “thirtysomething” without it. They met in the M.F.A. program at the American Film Institute, and would eventually form the Bedford Falls Company to produce their TV shows. That reference to “It’s A Wonderful Life” suggests both their interest in an earnest humanism besieged by doubt and darkness.

On the commentary tracks and extras of the “thirtysomething” DVDs, Zwick and Herskovitz speak of their desire to bring a cinematic sensibility to television. But where Michael Mann would, in “Miami Vice” and “Crime Story,” create a hypnotic, hallucinogenic unreality with his mise-en-scene, “thirtysomething” was a blend of the experimental and the everyday, the sketch comedy and the suburban drama. “Small moments examined closely” was the show’s mandate, which could mean a hyper-self-consciousness (as central protagonist Michael Steadman imagines himself trapped in a “Dick Van Dyke Show”-style black-and-white comedy), or moments of exquisite, almost banal quiet. “thirtysomething” was often mocked for its self-examination, but the layered visuals and experimental sequences twisted the straightforward dialogue into something more ironic and ambiguous: the characters might be painfully self-involved, but the show watched them with a distant-yet-sympathetic eye.

Those characters would become Third Age templates: Michael, whose angst over a career in advertising would slowly be shed when he came into contact with the Mephistophelean Miles Drentell (“Mad Men”‘s Don Draper is, in many ways, the blending of these two characters); Elliot, the man-child who is so often Michael’s id; Hope, the frustrated housewife who clings to her anger and self-righteousness as a bulwark against being sucked into Michael’s self-absorption; Ellyn, the career woman who looks at Hope with both pity and jealousy; Gary, the professorial Peter Pan; and Nancy, whose suppressed rage, quiet pride, and wry humor is tested by infidelity and illness. Reviews at the time suggested these were “Big Chill” rip-offs, but the advantage of television was time: instead of two hours, the characters could grow and regress (and grow again) over four years, each episode one more short story in the bigger collection.

The impact of “Moonlighting” and “thirtysomething” is everywhere. Their fourth-wall breaking and meta-humor can still be seen in contemporary comedies like “Community” and “Archer.” But it’s Third Age drama where the biggest influence is felt: “Mad Men”‘s unresolved explorations of family and gender; the dream sequences of “The Sopranos”; the unwillingness to settle on a single style or tone that defines so much of contemporary cable; and the way both shows end without really ending (“Moonlighting” pulls back to reveal the set of the show, breaking the fourth wall for the last time without resolving its subplots or even the mystery in its final episode; “thirtysomething” ends on notes of death, strained friendships, and uncertain marital futures, practically begging for a “sixtysomething,” just to tell us what happened).

They also offered strong, interesting female characters, which both Martin and Sepinwall admit is sometimes lacking in today’s more “revolutionary,” male anti-hero narratives. Another ABC show of the period, “China Beach,” would also offer a complex female protagonist as its center, and would also be short-lived: the Vietnam drama lasted only three years, and like so many shows of the Second Golden Age, took decades to reach home video (it’s a Third Age cable show through and through—dark, violent, open-ended, full of intertextual reference and formal play, with complex political narratives performed by a strong ensemble. Showtime would’ve eaten it up).

Constructing a history necessitates choices, and while I have a deep respect for all that Sepinwall and Martin accomplish, one side effect of their narrowing the definition of “revolutionary” programming is how much television it winnows out in the name of progress—and how often what it winnows out ends up being the less startling (but really no less resonant) broadcast and basic cable programming on Lifetime, the CW, A&E or USA. What would a history of this period look like that included “Gilmore Girls,” “Suits,” “Gossip Girl,” “The Vampire Diaries,” “The OC,” or “Army Wives”? Or just to choose a show Sepinwall covers really well—what would his book look like if it began in chronological order with “Buffy The Vampire Slayer,” instead of opening with four guy-driven HBO dramas?

Extreme Close-Up

The epilogue of “Difficult Men” opens with an epigraph from “Breaking Bad” creator Vince Gilligan: “Endings are the hardest part.”

This story started with a pair of cops in a fast-moving car, framed as if almost moving in slow motion. It ends with a pair of cops in a slow-moving courtroom, framed as if it’s the most kinetic space in the world.

Mike Post’s synth chord drops like a swooping airplane on the soundtrack, and a black screen gives way to a hand-held framing of a helicopter flying past a bridge. This, in turn, gives way to another hand-held shot of the same bridge, seen straight on; a left-moving pan merges with a cut to the expressway, then another cut to a different part of the expressway (the camera refocuses on a tugboat in the river). Three shots follow, all reframing the bridge and its commuter traffic, ending with a shot of a biker going from right to left across the same bridge. A swish pan left, back across the expressway, is covered in two separate shots, until another swish pan left takes us to a quick, blurry, half-framed courthouse, quickly reframed by a swish pan moving right, then back left again to finally settle on a the Criminal Courts Building.

The camera hasn’t actually covered a lot of space—it’s basically moved in a circle around the courthouse area—but it’s done so in about fourteen shots, all of which has taken only 28 seconds of screen time. Compared to the slow, stately cuts of “Miami Vice,” this is kinetic to the point of nausea: it’s impossible to get one’s bearings, but the imagery is vivid and alive, and the city is a real character—the first (and arguably most important) that we meet. This is the universe of “NYPD Blue.”

Inside the courtroom, the hand-held camera is still panning, its constant movement (and the voices of actors Dennis Franz and Sharon Lawrence) masking the fact that it introduces four of its five characters in one impressive, 16-second long take. A cut centers the camera on ADA Sylvia Costas (Lawrence), who is asking questions of Detective Andy Sipowicz (Franz), but director Gregory Hoblit’s framing is so deceptively casual that we might not notice a blurry background image of David Caruso, the program’s star, just over Costas’s left shoulder.

A quick cut shows us Sipowicz straight on, zooming in before cutting to a centered shot of Caruso’s Detective John Kelly, the camera slightly zooming again to get a better look at him. Two seconds later, it cuts to mob thug Alfonse Giardella and his lawyer James Sinclair. Another cut gives us a better view of Sipowicz, and again the camera slightly zooms to get us closer (it’s a shot that bonds Kelly and Sipowicz). A cut to a judge facing the opposite direction creates a slight confusion, which is built on in the next shot, where the hand-held sways left to right, as if caught unaware.

A repetition of the earlier shot of Costas follows, then Sinclair occupies the frame, his body rising with his voice. A cut to Sipowicz is ironic: it’s the steadiest framing on him yet, even as the prosecution’s case begins to fall apart. He can’t look at the camera (standing in here for Sinclair’s POV), and pushes his tongue against his lower lip. A set of three shot-reverse shots creates further stability, followed by a cut to Giardella sitting at the defense table; the camera pans left to Kelly, laughing as he hears tales of his partner’s slashing the tires of Giardella’s car and circumventing probable cause, then left again to Costas’ worried face in response, finally centering once again on Sinclair, dominating the center of the frame as much as he’s dominating the case.

Writer David Milch is playing with language here, but if you turn the sound down, there’s also a story unfolding on the purely visual level, about the relationship between movement and stasis. As long as the camera is roaming, there’s the chance of revelation, of a hustle; it’s the more traditional, more static framing that signifies failure. Hoblit is reversing visual expectation in this teaser as a pre-emptive strike for what the rest of the episode will do to the police genre.

The teaser continues as the characters leave the courtroom in an extreme long-shot, framed against the stairway and the massive marble wall that suggests how small they are in the face of a bureaucracy. Two long takes carry them downstairs and outside, framed in long shot against the steps. Throughout the teaser, Sipowicz’s verbal rhythms have been both earthy and ornate, the attempts of an out-of-control man to appear civilized. On the steps, his anger will reach a crescendo. “Hey, Miss District Attorney, you really prosecuted the crap outta that one!,” he yells.

They argue about who’s responsible for the loss. “I’d say res ipsa loquitur is I thought you knew what it meant,” Costas fires back. As she moves to the foreground Sipowicz is in the middle of the shot, Kelly in the back, all three figures in focus, like a law enforcement pieta. Sipowicz grabs his crotch off-screen (the camera cuts to Costas’ horrified reaction shot) and yells, “Ipsa this, you pissy little bitch!” As he leaves the frame, she turns to look back at Kelly, whose shrug suggests he’s been in this position before. The rush of an elevated train and Post’s drums leads into the opening credits.

Steven Bochco conceived of “NYPD Blue” as a response to rise of cable, and what he feared would be its encroachment on the strengths of broadcast drama: with the freedom of language, violence and nudity that cable offered, it seemed inevitable that the networks would lose audiences. Could there be a way to blend the more adult imagery of cable with the kinds of character-driven work (“Hill Street Blues” “L.A. Law”) on which Bochco had made his reputation?

As “NYPD Blue”‘s pilot unfolds, Sipowicz will further humiliate Giardella in public, which will lead to his suspension from the force, and a further spiraling down into his alcoholism; he will solicit sex from his regular weekly prostitute, which will turn out to be a set-up for his near-murder at the hands of an enraged Giardella. Meanwhile, John Kelly will grudgingly deal with his ongoing separation from his wife, and become involved with fellow cop Janice (who, it turns out, is mobbed up), which will lead to several famous shots of David Caruso’s bare butt. The language will be far more profane than in earlier cop shows, the sexuality more explicit, the violence slower and more graphic. Religious groups will frighten dozens of affiliates from carrying those early episodes of “NYPD Blue,” but it’s still a hit, and its surface shocks fulfill Bochco’s promise to push the envelope. But that’s not its legacy.

The reason the Second Golden Age closes with “NYPD Blue” has everything and nothing to do with Caruso’s backside. While the show definitely anticipates the sex of HBO, it’s the metaphorical nakedness—that desire to lay bare everything—that resonates across that first season. So much of the Second Age is about the balance between visual and verbal communication, each working with the other to deepen or flatten the narrative. On “NYPD Blue,” Hoblit’s ever-moving camera dovetailed beautifully with Milch’s layered prose—in both cases, there’s a gross expenditure of energy within a limited space, an interest in the way sentences and camera angles can pile up to create an almost Impressionist density.

If “thirtysomething” was intent on applying a mantra of “small moments examined closely” to suburban life, “NYPD Blue” was interested in minute, endless roaming around the human edges of large-scale criminality. Even more so than in their earlier shows, Bochco and Milch proved here how elastic a familiar genre could be, as cinematography, music, performance style and language blended to create a narrative that was fresco as much as novel.

But endings are the hardest part, and this balance couldn’t last—Hoblit left in the middle of the show’s second season to direct “Primal Fear,” and directors Mark Tinker and Paris Barclay brought a slower, more painterly framing and lighting into the mix, which transformed the show into something more baroque and theatrical, rather than televisual. Milch’s love of ornate reversed clauses would become an affectation that sucked out the individuality of each character, and when he left after the show’s seventh year, he took any knowledge of their motivations with him. Cast members would leave at an increasing rate each year, until only Franz remained from the original cast.

A show with six great years in it would run twice as long, a victim of its own success and an increasingly desperate network. When its seventh season was delayed in the fall of 1999 (just months after “The Sopranos” debuted on HBO) to make room for Zwick and Herskovitz’s “Once and Again” (produced through ABC’s parent company, Disney), Bochco complained to the press that his program was being “disrespected.” The show would run 22 consecutive episodes starting the following January, but this moment of network synergy was the book-end to Second Golden Age.

“You know what I love about this country?,” Miles Drentell asks Michael near the end of “thirtysomething”‘s final year. Its amazingly short memory. We’re a nation of amnesiacs. We forget everything. Where we came from. What we did to get here. History is last week’s People magazine, Michael.”

If “The Revolution” that Sepinwall and Martin celebrate could not find its full flowering because of various economic and cultural restraints networks faced in that earlier moment, it doesn’t undercut the achievements of those fifteen years, and their continuing impact on the “new new things” (to borrow Michael Lewis’s phrase) of this Third Age.

The problem with terms like “revolution” is the suggestion of a break with the past, the willful amnesia Miles cynically celebrates, rather than the time machine model that seems so much richer as it gathers writers, directors and stylistic pieces from many different eras. Surely, Sepinwall’s wonderful final passage on television’s cyclicality (“As [Ron D.] Moore was fond of writing on his classic series, all of this has happened before—and if we’re lucky, all of it will keep happening again, and again, and again”) is better served by a framework that allows its viewers to go around and around the medium’s history, and back again to its many homes.

Oh, and speaking of “all of it will keep happening again,” there’s a pretty decent new version of “Dallas” unfolding on TNT these days…