Michel Gondry‘s been persistently bedeviled by the adjective “quirky,” a word whose connotations suggest an untroubled whimsicality belied by the occasional darkness and social complexity onscreen. A 2009 profile titled “Michel Gondry — Eternal Sunshine of the Childlike Mind” is representative of the stereotyping of Gondry, with journalist Stephen Applebaum gushing over the director’s “child-like enthusiasm for making things” and his “wildly creative work that seems like the product of a child’s unfettered imagination.” This may be meant in a nice way, but such descriptions can cut both ways: “Other than being called childlike, the criticism that I most often receive is that I can’t really tell a story,” Gondry told Lynn Hirschberg in 2006.

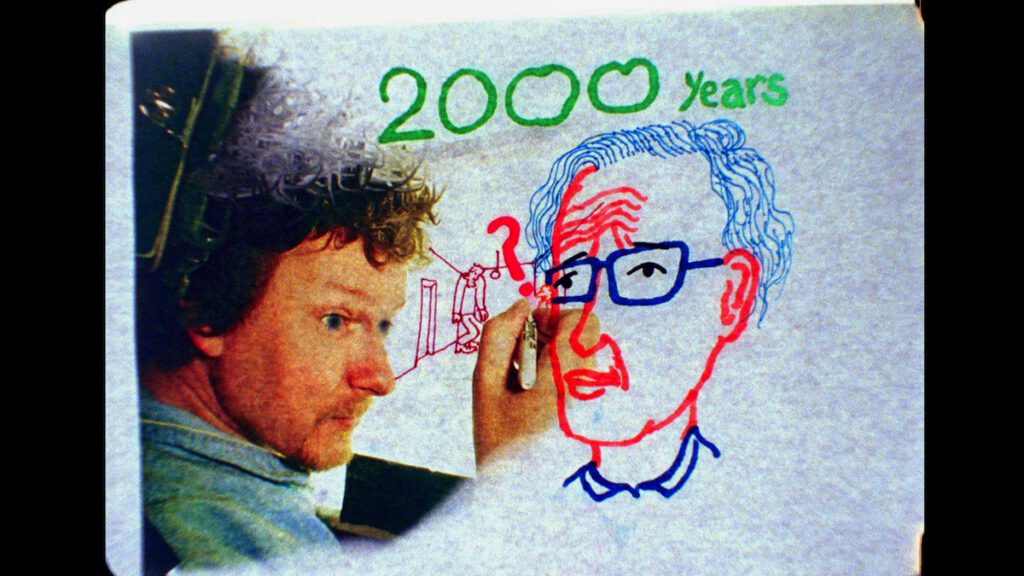

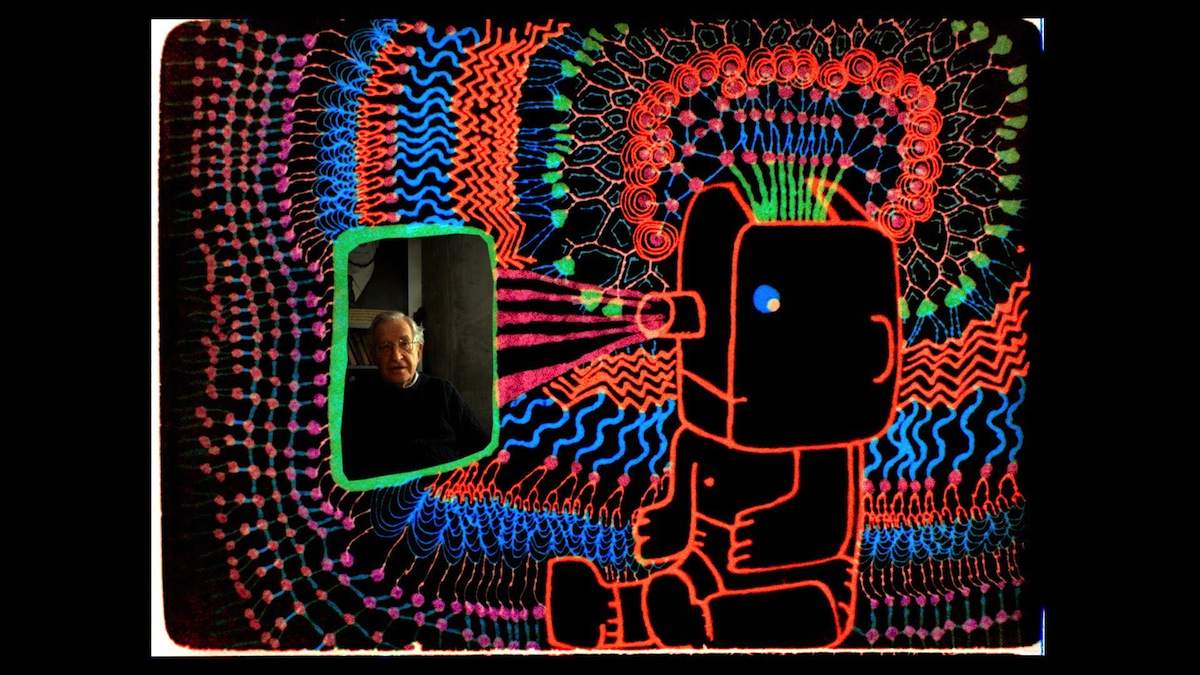

Gondry’s third documentary, “Is The Man Who Is Tall Happy?”, wants you to listen to Noam Chomsky discuss love, linguistics and perception; very undergrad, perhaps, but a long way from untethered froth. Mostly hand-drawn animation and a few real physical objects are looped into stop-motion back-and-forth, riffing on and against Chomsky’s words rather than simply illustrating them. An early image—a man whose head is a Bolex 8mm camera like the director’s own, projecting out images of Chomsky—presumably represents Gondry himself, meaning this is a conversation taking place in (or being beamed out of his) his head.

In Gondry’s flamboyantly impressive “Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind”, a depressed/depressive male weeps in agony in the opening scene, the kickoff to a first act that’s largely a sequential series of hard-to-sit-through end-of-relationship arguments; much of the film literally takes place in Jim Carrey’s mind. In Gondry’s next narrative feature “The Science Of Sleep,” Gael Garcia Bernal weeps on a bed with a Smiths poster on the wall behind him and has to have Charlotte Gainsbourg explain how girls (specifically, her) don’t like it when he spontaneously breaks down weeping. These two films feature the most continuous dream imagery and attendantly necessary technical trickery of Gondry’s cinematic career to date, but their generative centers are depressive, barely functioning men, socially isolated sources of imagery.

Between “Sunshine” and “Science,” Gondry released “Dave Chappelle's Block Party,” a concert movie that’s a celebration of black community on both a neighborhood level (in Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill) and in the music industry. De-centering the narrative focus from Chappelle to a more expansive group of not-equally-famous voices seems to have rewired Gondry’s interests a bit.

“When I did ‘Block Party,’ it was a lot about community and celebration, and I didn’t understand what they were celebrating, but I think I got at the end a sense of the idea that they were celebrating togetherness and celebration itself,” he said in a recent interview. “And I’m coming from a very average background, like white suburb, [in] which you don’t have a sense of community […] in day-to-day life, you didn’t really feel the need for community, and then when I met Dave Chappelle and I met all these musicians, I realized how community was something important. And so that was my point of view, I wanted to understand why it was important.”

In Gondry’s subsequent, he often allows others to speak about some rarely represented matters important to them, with minimal intervention: Mos Def commending Fred Hampton Jr. as “a good friend of mine […] an excellent gentleman” in “Block Party,” community organization in the face of neighborhood-dismantling gentrification in “Be Kind,” the sometimes excruciatingly unmediated and unapologetic cruelties of average teens in “The We And The I.” These aren’t the concerns of someone with an unmixedly “childlike” sensibility, and the films’ emphasis on telling stories of and about mixed-race, predominantly non-white American communities is a non-polemical, unforced constant corrective to minority under-representation on-screen.

Does Gondry deliberately hang back visually to make space for others in self-consciously drabber films? Absolutely, he says: in “The We And The I,” “I didn’t want to give my point of view, necessarily. I think my point of view comes in the way to listen, and then to shade the overall film, but I try to be as neutral as possible.” The narrative follows an often grim bus-ride home with honest, foul-mouthed, sometimes bullying, often objectionable teens —trailed at the outset by a miniature remote-controlled bus/boombox blasting old-school hip-hop. Young MC is decidedly from Gondry’s own collection rather than the kids’, as are stabs of Boards Of Canada’s vaguely sinister electronica.

2009’s “The Thorn In My Heart” is a tough-minded portrait of French provincial life in the home of his Aunt Suzanne and her gay son Jean-Yves, focused on the mother’s inability to accept her son’s sexuality. It’s mostly unostentatiously shot, but Gondry’s occasional punctuation—linking shots with miniature trains, kids given blue-screen “invisibility cloaks” to run around while Charlotte Gainsbourg sings—is unmistakable. Along with Gondry’s admittedly disastrous stab at big-studio filmmaking, 2011’s “The Green Hornet,” “Thorn “and “We” are probably the director’s least seen, most automatically written-off films. They’re his most consistently low-fi works, and the commitment here and elsewhere to allowing space for potentially tiresome voices to drone on (even/especially if they’re objectionable or confusing) is closer to Richard Linklater than, say, Gondry’s erstwhile music video colleague Spike Jonze. Both films have undeniable longueurs, but their tough-mindedness, social specificity and evasion of comforting cliches make them the kind of rewarding minor works that get undeservedly lost in sprawling directorial filmographies.

Gondry watches a lot of documentaries, probably more than fictional features in his estimation. He doesn’t mind if they’re formally indifferent as long as they have good information: “I watched several films of Doug Block, he did ’51 Birch Street,’ very personal about his family, they are beautiful but they could be shot on videos with smaller definition, I don’t mind at all.” The director had never encountered Chomsky until sometime in 2007 or 2008, when he rented a double-feature of 1992’s “Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky And The Media” and 2003’s “Noam Chomsky: Without A Pause.” The latter went direct-to-DVD in the States, but the former was a comparatively huge deal in the ’90s, the highest-grossing Canadian documentary up to that time and almost certainly a catalyst for Chomsky’s increased availability as a documentary/TV talking head on American TV. In bookstores (especially those near groups of collegiate youth), you may still find a shelf simply labeled “Chomsky,” an indication of the high esteem he earned decades ago and has maintained with embryonic liberals, and “Manufacturing Consent” can probably claim some credit for that. Gondry missed all this: his random rental led to him responding (in this order) “to his critique of the media and then his political views and then his scientific work. I always was impressed by the great scientists and how they bring… they have contributions to the evolution of knowledge, and I felt he was on the same level of the greatest, and he was still alive. And then I could meet with him, that was amazing.”

Time-capsule-ishly flavorful as a slideshow tour of student and community radio stations, lectures interrupted by angry frat boys and snippets of national TV broadcasts, “Manufacturing Consent”‘s 167 minutes are nearly entirely composed of Chomsky in direct public address mode. He’s repeatedly described as “the most important intellectual of our time,” a quote from the very same New York Times Chomsky makes one of his great Satans for its role in (he claims) intentionally suppressing reporting about American involvement in genocide in East Timor in the late ’70s. Depending upon probably one of the more grandiose descriptions possible from Chomsky’s sworn enemy of truth is probably the kind of awkward contradiction that led the linguist to have misgivings about the final film. One of his complaints was about receiving letters that asked “How can I join your movement?”, indicating that the writer failed to register the explicitly stated point that collective action was what Chomsky was calling for rather than a herd of admirers.

If the linguist (ostensibly) wants to avoid a cult of personality, Gondry’s goals for his film work against that. Chomsky’s allowed to speak for a bit about some activist causes near and dear to his heart—e.g. his agitation on behalf of Kurds in Turkey—and Gondry animates that, but then he steers him back to talking about the brain. That’s a way of respecting Chomsky’s overall concerns but then directing him back to the director’s turf sooner rather than later. Chomsky’s political side is “what’s shown of him mostly to the general public, and I thought […] I would do a more important job to get people to appreciate him as a human being, then they would listen maybe more to his political views and his environmental views. So that’s why I brought him to more personal subjects, and it’s not shown enough, I think he’s an interesting person and people perceive him only as an intellectual, but he has a very human aspect, I think, that I wanted to underline.”

Respect for POVs decidedly not the director’s own is a Gondry constant, and it’s far more germane than looking at his films as sporadic showcases for his visual imagination. “I think I want to show what listening is in my films, because I think it’s important,” Gondry explained. “People are generally more eager to give their point of view than to listen, like in a conversation it’s probably more exciting to express your own views than to listen to people’s ideas. So I want to show that when I do documentaries, and even in fiction film I try to be a good listener.” In this particular case, that means Chomsky gets an unusually large amount of time to express himself without interruption, a luxury he’s frequently complained of not having in the conventional media (which doesn’t stop him from being up for the occasional TV appearance).

Despite the hands-off space, a purely “Gondry-esque” intrusion is inevitable. In this case, when Chomsky doesn’t want to go into detail about life without his late wife Carol, Gondry plunges into an animated fantasy about a couple striding happily hand-in-hand through the clouds, wordless except for a Mia Doi Todd song. Gondry’s most self-consciously drab films make sure to include something that’s vaguely “Gondry-esque,” an imprecisely defined but easily recognized matrix of possibilities: retro technology, analogue visual trickery, casual technical ostentation. That’s a constraint as much as a promise: these moments can feel forced, as if Gondry were fulfilling an implicit obligation to momentarily dazzle before getting back to his Studs Terkel pose. This period as a sort of imaginative interviewer mostly indifferent to showing off is probably just a byway, but it’s crucial to the spirit of Gondry’s work. Chomsky is a lone man with a dream, but his activism emphasizes collective action, synthesizing the two sides of Gondry’s feature work thus far.