Sometimes I wish that the whole story of “The Other Side Of

The Wind” were some elaborate fiction, because then I wouldn’t have to deal

with the nagging frustration of not having been able to see the damn thing. The

frustration is different than the sadness I feel over the fact that “The

Magnificent Ambersons” is highly unlikely to be restored to its original form

in my or anyone else’s lifetime.

Readers who are already acquainted with the situations

concerning the two films I’m talking about—that is, readers who know a bit

about the life and career of Orson Welles, and if you consider yourself a film

lover, why wouldn’t you have this

knowledge?—know that the first mentioned film is a scintillating unfinished

one. And that the second is a terribly compromised masterpiece warped out of

its original form by a skittish and possibly malicious studio. Both movies are emblematic, in a way, of

Welles’ career, which maybe too many observers like to look at through the

scorpion-and-the-frog parable Welles himself relates in his 1955 pulp classic

“Mr. Arkadin.” A film that itself exists in at least three discrete

manifestations.

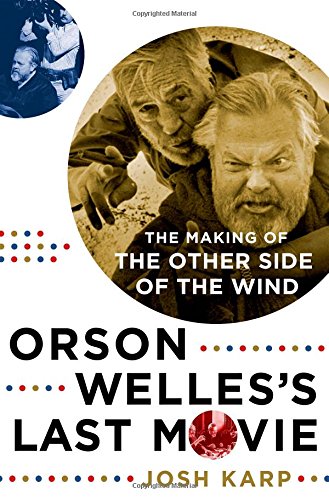

In any event, “The Other Side Of The Wind” is a real film,

and the story behind it is true, and crazy, and labyrinthine, and it gets told

cogently and mostly engagingly in Josh Karp’s book “Orson Welles’s Last Movie: The Making Of ‘The Other Side Of The Wind’.” Unlike many of the writers of

Welles-based books of the past two decades—most recent biographer Simon Callow

is an actor-director himself, Joseph McBride both a critic and one-time Welles

confidant, Jonathan Rosenbaum a longtime Welles scholar, to name three such

personages—Karp comes to his subject as a relative layman. This suits his

approach, because, unlike the recent volumes by McBride and Rosenbaum, “Last

Movie” is intended for the general reader. The theory seems to be you don’t

have to be a Welles lover to appreciate perhaps the greatest moviemaking

shaggy-dog story of all time.

And indeed is this a yarn. It begins with Welles himself,

considered washed-up as a filmmaking force even though as the story proper opens,

in 1970, he’s only 55 years old. Now best known as an overweight, plumy-voiced

fixture on celebrity roasts and talk shows, he’s still a cinematic rebel and

radical, and his idea for “Other Side,” a story of a washed-up filmmaker that

he insists is in no way autobiographical (and given the details of the scenario

likely wasn’t, at least not in the traditional sense) involves a way of

shooting that has more in common with the French New Wave than the studio

system in which Welles made not just his bones and his early masterpieces

(here’s where we mention “Citizen Kane”) but also plenty of enemies. The a clef

nature of his scenario will enable him to revenge himself here on many of those

enemies. And the process of making “Wind” goes on so long that Welles incorporates

new enemies into the movie as new real-life enemies appear, e.g., the critic

Pauline Kael, whose essay on the making of “Citizen Kane” Welles considered

highly deleterious to his future career, as well as slanderous to his past one.

Into the stew of his conception all sorts of characters

fall. From acolytes like Peter Bogdanovich and Gary Graver and old

co-conspirators such as John Huston and Mercedes MacCambridge. The cast is a

dizzying and eccentric crew, and Karp mines their observations and words to

create a portrait of mercurial and ever-whirring genius, that genius being

Welles as he, yes, immerses his collaborators in an intoxicating ritual of

never-ending creation. But this is only one Welles. Another Welles here is

unhappy, near-paranoid, tired of playing a magisterial role, capricious in

business dealings, self-sabotaging perhaps on purpose as the shoot stretches on

for years, the editing seems to stretch on for decades, and the movie is lost

in a morass of financial and political machinations. Yes, the movie’s

connection with the deposed Shah of Iran is laid out clearly. To Karp’s credit,

he is unsparing in detail about all the deal and contracts that tangled the web

of this movie’s fate. They can be tedious, sure, but I think even a lay reader

ought to be acquainted with some of the more stygian depths of movie financing,

so as never to fall for the ignorant adage about personal-style filmmakers

making “one for themselves, and one for the studio.”

Karp’s book isn’t perfect. Early on, he commits the grave

error of trying to impersonate Welles’ writing voice, and fails so

flat-footedly that it almost doesn’t matter. Twice in the book he uses “infer”

when he means “imply” (and the man teaches journalism!). His explanations of

Welles’ greatness are respectful (unlike a lot of other folks approaching

Welles anew, he doesn’t hold any truck with the idea that Welles’ post-“Citizen

Kane” filmography is one big long “nothing to see here”) but are likely to try

the patience of those who already hold the maestro in great esteem. The book

ends before the most recent developments in the story, which included a feint

at a “Wind” screening for Welles’ 100th birthday, at Cannes this

year. Which didn’t happen. And now an Indiegogo campaign to finance the film’s

completion is happening. It ends soon. I contributed, and part of me wishes you would too. Another

part of me keeps remembering Charlie Brown, Lucy, and the football.