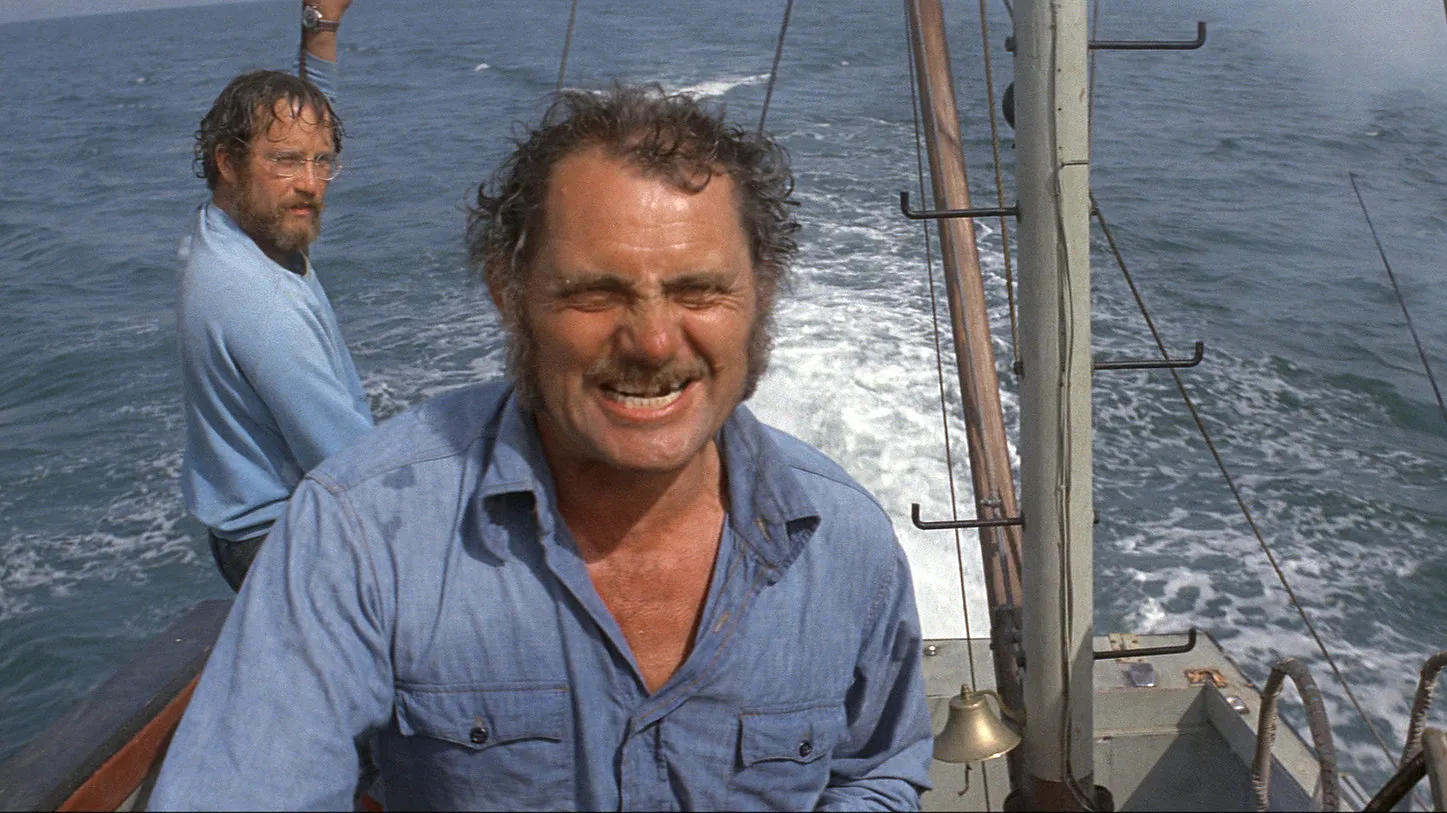

As many times as I’ve seen “Jaws” since I first experienced it as a mesmerized, terrified, and thrilled 15-year-old in the summer of 1975, each revisit yields something new, something that didn’t fully register with me the first time I saw it. I’m long past the point where I’ll be shocked by that first tug on late-night skinny-dipper Chrissie Watkins, or the jump-scare appearance of Ben Gardner’s severed head, or the moment when the shark appears behind Chief Brody and we see it just before he does. Now, though, it’s all about catching something that would only resonate upon repeated viewings—and about appreciating the layers of brilliance in the performances by Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, Richard Dreyfuss, et al.

It was maybe the third or fourth time around for me when I noticed some blocking in an early scene that had escaped my attention. After Scheider’s Amity Police Chief Martin Brody takes a call from the Medical Inspector and types “SHARK ATTACK” under “Probable Cause of Death” for Chrissie, Brody walks briskly through the village square, almost seeming to keep time with the band that can be heard in the distance as it rehearses for the town’s 50th annual regatta. Along the way, cinematographer Bill Butler’s camera briefly captures some telling background business. First, we see a man in a gray suit who turns out to be the Medical Inspector (played by Robert Nevin, a real-life doctor); next, we catch a glimpse of the editor of the Amity Gazette, one Harry Meadows, played by “Jaws” co-screenwriter Carl Gottlieb. Both men are emerging from their places of work to meet up with Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton).

Flash forward a few moments: Brody is on the ferry when a 1974 Cadillac Coupe de Ville in Terracotta Firemist with a “VAUGHN’S REALTY” sign on the door pulls up. To be sure, Vaughn leads the effort to dissuade Brody from closing the beaches—but he’s backed up by Meadows, who downplays the possibility of a shark attack (“…we’ve never had that kind of trouble in these waters”) and by the Medical Inspector, who agrees with Vaughn’s theory Chrissie could have been sliced up by a boat propeller, saying, “Well, I think possibly, yes, a boating accident.” When Brody says, “That’s not what you told me over the phone,” the M.I. replies, “I was wrong. We’ll have to amend our reports.”

Much has been made of the parallels (intentional or not) between Watergate and “Jaws,” which was filmed in 1974 and was released less than a year after Richard Nixon resigned, and how themes of paranoia and distrust of the government run through the film—but whereas the journalists Woodward and Bernstein were heroes who in a couple of years would be portrayed by Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman in “All the President’s Men,” the so-called reporter in “Jaws” as well as the Medical Inspector are also complicit in the cover-up and the denial of the facts. When the late Alex Kintner’s mom (Lee Fierro) offers a $3,000 reward for the capture of the shark that killed her son, Meadows tells the mayor, “It’s a small story. I’m gonna bury it as deep as I can.” Later, Vaughn says to a television interviewer, “I’m pleased and happy to repeat the news that we have in fact caught and killed a large predator that supposedly injured some bathers…”

The unconscionable corruption leaves you breathless. (That Vaughn was STILL the mayor in “Jaws 2” has inspired countless memes.) Larry Vaughn ranks among the most hiss-worthy villains in movie history, and rightfully so. He did not, however, act alone. Much of the town, most notably the upper-class business operators, refused to acknowledge a predator lurking in waters off the beach until Chrissie Watkins, Alex Kintner, Ben Gardner, and the Estuary Man had been gobbled up in rapid succession. Only then did the shell-shocked Vaughn sign off on Shaw’s Quint going after the great white shark. Even Brody, a decent family man and good cop, capitulates to Vaughn et al., agreeing to keep the beaches open far too long. When Mrs. Kintner cracks Brody across the face, he has it coming.

Speaking of victims, we’d also be remiss not to mention Pippit the dog! To Spielberg’s great credit, he ramped up the stakes when the shark killed a dog and a child. From that moment on, we felt that no one was safe in the water.

Given the level of intensity and the amount of blood spilled, it might come as something of a surprise “Jaws” was given a PG rating—but it was either that or an “R,” as the PG-13 designation wasn’t implemented until the summer of 1984. The well-chronicled problems with the mechanical shark no doubt inspired Spielberg to amp up his game, from the tracking shots shown from the P.O.V. of the shark, to the legendary dolly zoom on Chief Brody’s face as he witnesses an attack from the shore, to the creative use of water-level shots. “Jaws” is also a masterclass in pacing and sound, with John Williams’ iconic score (arguably the most imitated and parodied in the history of movies), Verna Fields’ editing and the sound team of John Carter, Roger Heman, Robert L. Hoyt and Earl Madery winning Academy Awards. (Sidebar: it’s insane that Spielberg wasn’t nominated for Best Director, Scheider wasn’t nominated for Best Actor, and neither Shaw nor Dreyfuss received Supporting Actor nods. All great respect to James Whitmore in “Give ‘em Hell, Harry!” and Burgess Meredith in “The Day of the Locust,” but when was the last time you heard anyone talking about those films and those performances? “Jaws” had a total of four Oscar nominations. It should have had at least eight or nine.)

Another element I’ve come to appreciate over repeated viewings is how Spielberg and screenwriters Peter Benchley (who cameos as the TV journalist who interviews Vaughn) and Gottlieb, with a great assist from casting director Shari Rhodes, created such an authentic slice of summer life. There are times, especially in the early going, when it’s almost as if we’re watching an Americana comedy from Preston Sturges or Frank Capra, as when local Martha’s Vineyard resident Peggy Scott does a scene-stealing turn as Polly the secretary, who tells the chief, “Now we got a bunch of calls about that karate school. It seems that the nine-year-olds from the school have been karate-ing the picket fences,” punctuating that last part by making little karate chops. (Also unforgettable: Alfred Wilde as the old coot “Bad Hat Harry,” and local fisherman Hershel West as Quint’s mate, Salvatore.) There’s something darkly funny about the moment when Brody and Hooper (Dreyfuss gives such a wonderfully high-octane performance) visit the Medical Inspector’s lab to examine Chrissie’s remains—and instead of a body on slab, all that’s left of Chrissie is in a tub that could fit into a dishwasher.

Even after the body count increases, “Jaws” finds room for sly humor, as when Hooper shows up uninvited at the Brody house with two bottles of wine. Brody uncorks the red and pours it right into his nearly finished glass of what appears to be whiskey, ignoring Hooper’s pleas for him to “let that breathe…” Gottlieb’s background included writing for smart comedies such as “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” “The Bob Newhart Show,” and “All in the Family,” and those chops are evident in the dialogue here.

It’s nigh impossible to run out of things to talk about when we dissect “Jaws.” How Quint’s reference to his friend “Herbie Robinson, from Cleveland,” being “bitten in half, below the waist” by a shark after the U.S.S. Indianapolis sank foreshadows Quint’s own demise. The scene where the waves of tourists descend upon Amityville on the 4th of July, metaphorically swallowing up the island. How movies ranging from “Alien” to “Signs” to “A Quiet Place” to “Nope” are cinematic descendants of “Jaws.” The wise choice by the filmmakers NOT to keep the book’s subplot about a brief affair between Hooper and Brody’s wife, which would have turned the entire movie upside down. How we’re still not sure if that grim-faced man who accompanies Mrs. Kintner to the dock is her father or her brother—or maybe an attorney or a funeral director.

Maybe I’ll find a clue in my next rewatch.