Going to the movies has always been one of the simplest,

most democratic of life’s pleasures. Almost from the moment they were invented,

anyone with some loose change in his or her pocket could walk up to the box

office, purchase a ticket, and sit and watch a movie. With such easy access,

it’s no wonder a love of movies has survived for going on over a century now.

But the near back-to-back development of two news stories in

the movie business have stuck in my craw. They seem to crystalize a recent trend

in movie culture where a love of photochemicals has been conflated with a love

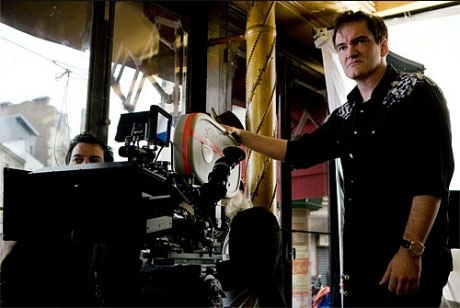

of movies. Quentin Tarantino’s taking over programming duties at the New

Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles and Christopher Nolan’s “Interstellar” being

offered to theaters equipped with film projectors two days before its initial

release illuminate a form of exclusivity going on in movie culture that, I

think, is unhealthy.

Now, this editorial is not a sky-is-falling warning about

the “death of film.” (I leave that to Godfrey

Cheshire.) Nor am I wanting to make a case for digital being superior to

celluloid. This is more about an attitude, a way of thinking that creates

divisions where there really shouldn’t be.

Tarantino’s programming duties at the New Beverly are being

hailed as some kind of rallying cry by movie lovers who are upset by the

phasing out of 35mm prints in favor of DCPs for revival screenings. At a press conference at this year’s

Cannes Film Festival, Tarantino decried the “death of cinema” (as he knew it)

and bemoaned that digital projection is basically “television in public.” He

did acknowledge that digital cameras have made it easier for anyone with enough

ingenuity and determination to go out and make a movie, but that doesn’t really

interest him. Shooting on celluloid, which is both expensive and

time-consuming, represents something pure to Tarantino and other like-minded

filmmakers and movie buffs. When the people at the Cannes Film Festival decided

to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Sergio Leone’s “A Fistful of Dollars” by

having it as the closing-night movie, they asked Tarantino to introduce it. He

excitedly did, but was depressed throughout the screening when he discovered

they were showing a 4K digital restoration. He missed the flicker effect.

What does all

this mean? Well, if I wanted to be snarky it sounds as if Tarantino and others

like him have fallen in love with sprockets. The unveiling of the October

schedule for the New Beverly was greeted with hushed reverence as the Internet

drooled over the “coolness” of some of the double features. All of the movies

shown at the New Beverly will be either 35mm or 16mm prints. Some will be new

or archive prints, while others will be taken from Tarantino’s personal

library. For example: Howard Hawks’ incomparable “His Girl Friday” is a newly

struck print, while “Junior Bonner” is a personal print. Tarantino is proud of

his “Junior Bonner” print because it is “washed-out” and “beaten up.” It has

character.

And it is

the putting a premium on “beaten up” celluloid that has stuck in my craw. You

may have noticed that I am being very careful to use the word “celluloid” when

discussing this issue. This is because a fondness of “celluloid” or “film” has

nothing to do with storytelling. The communal experience of going to the movies

has very little to do whether a given movie is going to be shown in 35mm. Or

does it? Tarantino, Nolan, and other proponents of celluloid would have you

believe otherwise, and I feel this is creating an exclusionary,

what-the-cool-kids-are-into mentality that is quite toxic to the movie-going

experience. You’re made to feel if you go to a revival screening, and it isn’t

being shown in 35mm, you’re somehow missing out. You’re not getting the full

experience.

Tarantino’s

“television in public” battle cry misses the whole point of what marks the

difference between the two mediums. He seems to think it’s a matter of film vs.

digital, when anyone knows television has been shot on both tape and film

almost from its inception. The “flicker effect” of movies is only one small

component of going to the movies. Going to the movies involves a group of

strangers getting together and sharing the experience of looking up at the

movies. Watching television is more solitary and has the viewer looking down or

straight ahead. Movies are designed to overwhelm us with emotions. Most

television is more cerebral, with a shelf life of seven days. And no matter how

big a TV monitor you have you still can’t replicate the movie-going experience.

Not because you’re watching a DVD, but because you’re not sharing the

experience of looking up at the screen.

The “Interstellar”

release is a stickier situation. Ever since “The Dark Knight” (2008), Nolan has

used the IMAX format to highlight key action sequences in his movies. The

results have been impressive, especially in “The Dark Knight Rises” (2012),

where the climax played like Eisenstein writ large. “Interstellar” is being

whispered as Nolan’s “2001.”

It was shot in both 35mm and 65mm. But

unlike previous IMAX releases of Nolan movies (which were simultaneous with

regular digital exhibitions), or the early IMAX release of “Mission:

Impossible–Ghost Protocol” (which was done primarily as a promotional stunt for

the wide release), this two-day exclusive engagement for any theater with a film

projector smacks of “Members Only” grandstanding. After years of resisting

change, theaters finally relented to studio pressure and changed over from film

to digital projection. According to an article in The Hollywood Reporter, 240

screens in 77 markets will be getting “Interstellar.” That’s a little more than

five per cent of all the screens in the country. (It breaks down like this: 189

with 35mm; 10 with 70mm; 41 with IMAX.) In the same article, theater owners are

quoted as being upset that they’re missing out on this opportunity. It is too

costly to retrieve a projector from a warehouse just for a two-day engagement.

Plus, many of the small theater chains no longer employ a person who knows how

to work a film projector. So, while the studios and a group of directors

face-off in a game of artistic chicken, theater owners and the majority of the

movie-going public are made to feel as if they’re missing out.

Back in

1977, when the original “Star Wars” came out, different versions of the movie

were offered to the public. You had both 35mm and 70mm engagements. Along

with those two versions came different audio mixes (mono, stereo, six-track

stereo). Lucas and 20th Century Fox did what was necessary to

accommodate the varying types of theaters around the county. What was most

important about the release was that everyone got to see “Star Wars.” My, how

things have changed. This emphasis on film stock is shutting out movie lovers

who don’t live within a major media market (which means a vast majority of the

movie-going public). I worry about the movie lover who is being made to feel

like they’re missing out on something because they don’t live near New York or

Los Angeles or Chicago or Seattle or Austin or any hip movie scene. (When “2001”

first came out it was a badge of honor to boast about how far you drove to see

it in a Cinerama theater.) Directors and movie geeks who go on about “shot on

film” or how a revival screening was “shown on 35” are revealing more about

themselves than about the movies. It’s all part of the fascistic fanboy culture

in which “celluloid” is being used to represent something besides a means of telling a story.

I

admit there is something to be said about seeing a movie projected on film. Two

years ago, I made a trip to Austin to see Paul Thomas Anderson’s 70mm character

study “The Master.” It was cool, but I realized afterwards, despite the clarity

of seeing Philip Seymour Hoffman’s pores, the trip didn’t add anything to the

story. The movie was still an at times riveting, at times remote experience. I

happen to live in a market (San Antonio) where we have an authentic IMAX

screen, so that means I’ll be seeing “Interstellar” two days before everyone

else. What I feel is needed is a little bit of caution and consideration when

it comes to sending out a distress signal.

Interestingly, Anderson addressed this issue in his even-handed way over the weekend at the New York Film Festival. His latest movie, the Thomas Pynchon adaptation “Inherent

Vice,” was the only movie being screened at the festival in 35mm. Anderson was

asked about this at that post-premiere press conference. Not wanting to make a

big deal about it, he quietly said, “Just trying to keep it alive a little bit

longer…Not to phase anything out; there’s room for both things.”

Spoken like

a true lover of movies.