O.J. Simpson, who saw his 1970s and 80s genial public image as an attractive athlete and sometime performer eclipsed by his acquittal for the murder of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman, has died of cancer at age 76, according to his family. In his early years, he was a record-setting college and NFL football star, commercial spokesman, and television and movie performer. In his later years, he was utterly disgraced, any connection to him as an individual all but obliterated by his symbolism as an attractive, talented, wealthy Black man who was, depending on your point of view, unfairly acquitted of murder or brought down by daring to be successful. He is better known today for the award-winning documentary about his life (“OJ: Made in America”) and the narrative series about his trial (“American Crime Story: The People vs. O.J. Simpson”) than for winning the Heisman trophy or appearing in movies and commercials.

His death follows closely those of Black male actors Jim Brown, Richard Roundtree, Carl Weathers, and Louis Gossett Jr. To varying degrees, these men shifted the character arc of Black men in Hollywood, from the dignified but harmless roles of Sidney Poitier to figures of action, rebellion, and overt sexual appeal. On the heels of more outspoken Black male sports personalities such as Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown and Bill Russell, O.J. Simpson was embraced as a clean cut, marketable alternative. His jovial off-field image and Southern California fame invited opportunities. Before Sugar Ray Leonard or Michael Jordan, Simpson was the most bankable Black athlete. While limited in his cinematic or television performance range, his renown lent appeal to his films and roles. He represented Black virility in an unthreatening mode.

In the nearly six decades in which he has occupied the national spotlight, Simpson has been associated with heroism, humor, and hubris. On the small and large screen, his appearances might be characterized as “stunt casting.” No one would call him an actor perhaps in part due to his struggles with literacy, which, behind the scenes, affected his ability to read screenplays and cue cards, and a pronounced “lazy tongue,” which sometimes caused him, especially during live sportscasting, to stumble over words. His success in the years following the end of his career in sports was entirely due to a public impression of him as a “good” minority; a CEO could brag about having played a round of golf with him. The murders, the circus of a trial, the divisive verdict, and his cagey denials made even casual fans unsettled and uncomfortable. It is telling that the criminal conviction that finally sent him to prison came from his effort to retrieve memorabilia of his better days.

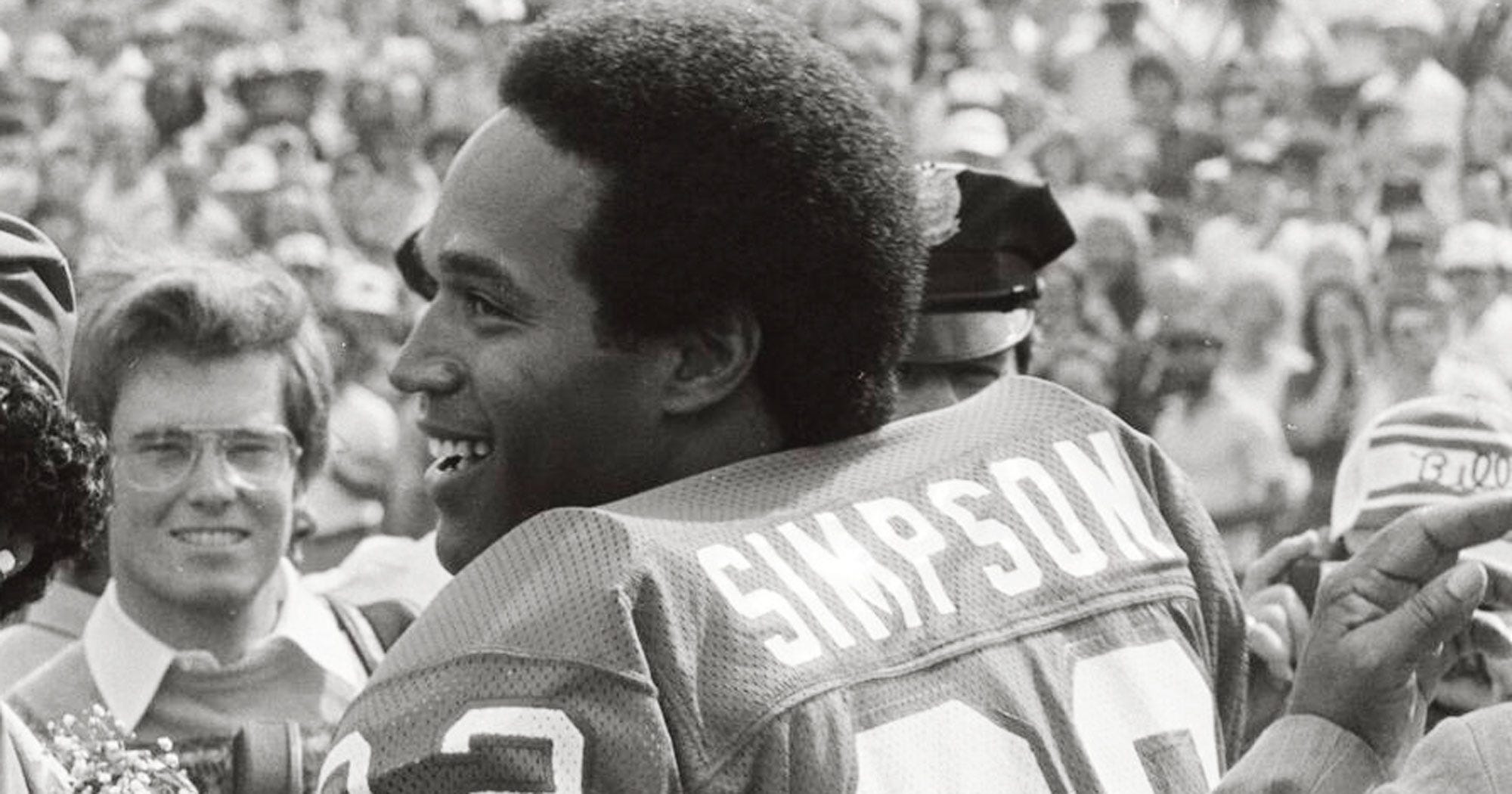

O.J. Simpson was born in San Francisco in 1947, to Eunice and Jimmy Lee Simpson. As a youth, his brushes with the law earned a court appearance by baseball superstar Willie Mays, who told a juvenile affairs judge that 14-year-old Orenthal James Simpson had athletic potential if he were pardoned this once. Simpson parlayed his high school track and football stardom into enrollment at San Francisco City College, where he captured the attention of athletic recruiters from the University of Southern California. In 1967, O.J., newlywed to high school sweetheart Marguerite, enrolled at USC. He was not long on the campus before he participated in a world record (which still stands) 440 relay team. Varsity football beckoned. On the gridiron, in the three-network TV era, Simpson, nicknamed “Orange Juice” by media, became an overnight celebrity. His nationally televised exploits thrilled fans, and, in 1967, he faced UCLA’s own Heisman Trophy candidate, quarterback Gary Beban, in a nationally broadcast rivalry game billed “The Game of The Century”. The next season, Simpson was awarded the Heisman trophy. In only two seasons, he had shattered the NCAA’s career rushing record.

The hapless Buffalo Bills selected him as the first player in the 1969 AFL-NFL Draft. Simpson’s TV career began before he ever donned a Bills uniform. That summer, he began work as an actor in the season premiere of a new TV drama called “Medical Center.” He portrayed a promising pro football player diagnosed with a rare disease. Simpson’s advertising career began in earnest in a TV spot featuring the rookie running back in his three-point stance, as the narrator declares that the new car being advertised “… also runs on less money than O.J. Simpson.” Upon the remark Simpson glares at the camera.

After a rough rookie start, and unimpressive sophomore campaign, Simpson emerged as a star for the Bills, and the endorsement deals kept coming, perhaps most famously, for auto rental giant Hertz. In one famous campaign, Simpson exited his rental, and dashed through the airport, hurdling obstacles in his way. He spoke the tag line, “The Superstar in Rent-a-Car” and joined the company’s corporate board of directors. Simpson also had a minor, but equally typical role, sprinting to avoid possible enslavement in the landmark TV miniseries “Roots.” A few years into his pro football career, he also did studio announcing work for ABC Sports.

By the middle 1970s, Simpson was often voted one of the most admired Americans, and in 1977, one of the country’s three most recognizable people. His athletic career was winding to a close. Simpson’s feature film career began in 1973’s “The Klansman,” followed in the 1974 blockbuster “The Towering Inferno.” In the 1978 sci-fi “Capricorn One,” he portrayed an astronaut. Ten years later, aged 41, he joined the ensemble of the comedic “The Naked Gun” franchise. Simpson’s final appearance in these cop capers was in 1994’s “Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult.” He was 47.

On June 12, 1994, Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman were brutally murdered outside her home. O.J., who had a history of domestic violence against both Marguerite and Nicole, including police being called to their residences, was pursued by the L.A. police as a suspect. Rather than report to the police, on June 17, he and childhood friend and former Bills teammate Al Cowlings, who had dated Marguerite before O.J., fled from law enforcement in the now infamous white Ford Bronco, and all across America, audiences saw it on television, forever changing the way people watched breaking news.

1994 was the tail end of the three-network dominant era of U.S. TV. Cable news outlets were rising in prominence, featuring 24-hour news coverage. In that ecosystem, the pursuit, subsequent arrest, and highly publicized criminal trial of one of the country’s most famous figures, captured the nation’s attention. Questions of his guilt, innocence, or privilege, exposed and inflamed a racial divide some white and Black people may have previously underestimated.

For tens of millions of viewers, the Simpson criminal trial was daily TV viewing. This “popularity” helped trigger the creation of daytime court and legal television series and gave birth to celebrity judges and star jury experts like Judge Judy, Dr. Phil, and Judge Greg Mathis. The trial also catapulted participants such as attorneys Marcia Clarke, Chris Darden, Johnnie Cochran, and controversial witnesses Kato Kaelin and Detective Mark Fuhrman, and attorney Robert Kardashian—yes, father of Kourtney, Kim, Khloé, and Rob and then-husband of Kris Jenner—into being public figures. The colorful Cochran’s argument to the jury about a glove found at the scene that “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit” was made for television immortality.

When Simpson was acquitted of double murder, while crowds outside the courthouse awaited the verdict, and TV networks aired it live, some Black viewers, from the streets to HBCU law schools, were shown celebrating the decision. Others, including many Black onlookers, wondered what the jurors could have been thinking. National debates sprung up around the nuances between “not guilty beyond a reasonable doubt” and “innocent.” For some Black observers, O.J. had been more of a racial sellout than a community hero, but his legal victory symbolized Black status finally achieving the perks and freedoms of white counterparts.

Civil cases require a lower burden of proof. Three years later, a Santa Monica civil jury found Simpson guilty of Goldman’s murder, and battery of Brown in a case brought by the Goldmans and Browns. The football star was ordered to pay damages to both families. Through it all, O.J. proclaimed his innocence, and remained in the public limelight, writing books about his case, one chillingly titled, If I Did It, but still claiming he was trying to find “the real killers.” This made him an even more lasting and divisive media presence.

In the ensuing years, Simpson has been arrested for battery during a 2001 Miami road rage incident, and armed robbery and kidnapping for an effort to retrieve some of his sports memorabilia at gunpoint in a Las Vegas hotel room in 2007. Convicted with co-conspirators, Simpson served nearly nine years in prison for those crimes. He was released in 2017. That same year, Ezra Edelman’s ESPN miniseries “O.J.: Made in America,” which examined U.S. history from the middle 1960s to the then-present with the Simpson double murder criminal case as a prism, won an Academy Award for Best Documentary. Simpson continued to voice his own—often controversial and provocative—opinions via his social media platforms. He never appeared to be ashamed or tainted by his violent past or embittered, or even aware, of his fall from grace.