“The wreckage of my past is haunting me, it just won’t leave me alone,” sang Ozzy on “Road to Nowhere,” the reflective closer on his bestselling 1991 album No More Tears. It’s a standout in a solo career that endeared him to Gen Xers as much as his Black Sabbath albums did for boomers and The Osbournes for millennials, by which point Ozzy’s status as a top-tier rock legend was irrefutable. The establishment didn’t take him seriously—his first Rolling Stone cover story wasn’t until 2002 (he graced the cover twice that year), and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame didn’t induct Sabbath nor Ozzy solo until many years after their earliest eligibility. That may have endeared Ozzy all the more to fans who packed amphitheaters for Ozzfest and bought millions of his records that FM radio was hesitant to play. Like David Lynch or Pee-wee Herman, he was a very public weirdo who offended puritans and made other weirdos feel safe. People wanted to dismiss this pastor-terrorizing, bat-chomping, Alamo-desecrating hellion as a shock-rocker, but those of us who listened knew part of what made the Ozzman such a striking artist was how hard he worked to convince us of the opposite.

In Penelope Spheeris’ unforgettable “The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years,” rockers are eager to be filmed showing off their excesses—beset by young groupies, or chugging vodka in a private swimming pool, perhaps. Ozzy gave the most memorable interview by showing himself making breakfast in his kitchen. (We now know that the orange juice spill is staged, which further speaks to Ozzy’s humor.) He constantly dismissed his music’s heaviness (“I’ve never felt comfortable about that title that they put on me — ‘metal,’…it was always just rock music”), Satanism (“We couldn’t conjure up a fart”), and annoyed his more serious bandmates by jumping around on stage too much. He duetted with Miss Piggy on the 1994 Muppets album Kermit Unpigged. He was far more likely to sing the praises of the Beatles or Peter Gabriel than his Ozzfest brethren, though he certainly elevated numerous young and underappreciated artists on tour.

He insisted Black Sabbath were “the last hippie band” (“We were into peace”) and sang about leaning to love and forgetting to hate in his biggest solo hit. Most famously, he played the befuddled father on an MTV show that may have been the worst possible publicity for someone widely known as the Prince of Darkness, or the Godfather of Metal. In a Rolling Stone profile riding on the success of the hit show “The Osbournes,” Ozzy recounted being recently invited to Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee, where he bashfully tried to cover up his tattooed fingers (O-Z-Z-Y) for the monarch. He differentiated himself from other rock stars by noting that he stayed married to someone his own age. Ozzy wasn’t trying to get people to ignore the man behind the curtain, he wanted to reassure us the man on stage wasn’t so bad.

But like the wolfman Ozzy sang about in “Bark at the Moon,” or the Robert Louis Stevenson character he referenced on an Ozzmosis deep cut, something horrifying kept breaking out of John Michael Osbourne. No matter how much he downplayed his dark side, there was something unpredictable and unnerving in his persona. No other rock musician can seem so convincingly possessed. Part of it was the debauchery—if Ozzy’s peers and his fabulous autobiography I Am Ozzy are to be believed, he lived through and forgot about more depravity than most rock stars have enjoyed (anyone who can gross out the members of Mötley Crüe is on another level). But the most stunning thing about Ozzy Osbourne will always be his music. “I don’t want to change the world, I don’t want the world to change me” chanted Ozzy in another No More Tears banger, which eventually (speaking of shocking) won him a Grammy. No matter what he intended, the world changed for Ozzy Osbourne, a troubled, impoverished boy from an abusive household, a high school dropout with undiagnosed ADHD and dyslexia, who struggled to fight off bullies or hold down a steady job, and grew up to be one of the most celebrated artists of his lifetime.

Ozzy had worked as a plumber, tea boy, slaughterhouse employee (“The stink was unbelievable”), mortuary assistant (“I’d have visions of the dead people’s faces when I got home”), and car horn tuner (“Can you imagine being in a room with that fucking racket?”), as well as spent time in jail (“The best thing my father ever did for me was he refused to pay the fine”) by the time he started placing ads to start a band. He found Black Sabbath, which sounded like nothing before it when their first album dropped in February 1970. Every metal act in their wake owes something to them.

It’s still startling how contemporary Sabbath still sounds with today’s cutting-edge metal bands. Purists like to point out that guitarist Tony Iommi was the riff architect and bassist Geezer Butler wrote most of the band’s lyrics, while Sabbath’s reunion minus original drummer Bill Ward emphasized his critical percussion. But Ozzy’s ability to own and define songs he didn’t write underscores his place as heavy metal’s Elvis, its first global superstar arriving as a jaw-dropping, irreplaceable talent.

Nobody sings like Ozzy—most metal vocalists are operatic (Rob Halford, Bruce Dickinson) or growlers (Lemmy, James Hetfield), none of whom can achieve Ozzy’s banshee wail. He could pull off wild harmonies with himself through multitracked vocals or go from singsong to maniacal within seconds. He articulated insecurity (“Goodbye to Romance,” “Tonight”) and uncertainty (“I Don’t Know,” “Time After Time”) as well as the most rowdy or foreboding characters he’s known for.

He articulated insecurity, uncertainty, and even love as well as the most rowdy or foreboding characters he’s known for. It was not the kind of voice people develop with singing lessons. Ozzy may have the distinction of being both metal’s most influential and inimitable vocalist. Analyzing some of metal’s biggest vocalists in a feature for metal blog Invisible Oranges, renowned voice teacher Claudia Friedlander noted that the “War Pigs” singer’s technique was all wrong, asking, “How long did his career last?” Ozzy’s howl didn’t sound like it was meant to last, which is part of what kept us hooked to every note, even as he seemed to withstand every ingested narcotic, vehicle collision, deadly illness, or other catastrophe thrown his way.

When Ozzy was unceremoniously fired from Black Sabbath in 1979, one could be forgiven for thinking he’d be metal’s Art Garfunkel, adrift without his corresponding songwriters. But with a help of a new team (Ozzy was always quick to attribute his solo success to wife/manager Sharon Osboune and prodigy guitarist Randy Rhoads), Ozzy forged a new path on his knockout solo albums Blizzard of Ozz and Diary of a Madman, pioneering a speed metal sound with enough pop hooks to make songs like “Mister Crowley,” “Over the Mountain,” and “Flying High Again” into eventual anthems, armed with the most innovative young rock guitarist this side of Eddie Van Halen.

Like a metal Iggy Pop with David Bowie, Ozzy and Rhoads will always be linked as collaborators for their two genre-changing albums together, establishing the frontman as his own astonishing voice rising from his previous band’s implosion. After Rhoads was tragically killed in a plane crash, Ozzy soldiered on with new guitarist Jake E. Lee for some less consistent albums that still have some gems and a deserved following. Ozzy seemed to have more fun than ever when the Satanic Panic preachers and PMRC parents started blaming him for society’s ills, and he was happy to mock Jimmy Swaggert in the “Miracle Man” video or play a televangelist in 1986 horror movie Trick or Treat. Looking back at the goofball on the cover of Diary of a Madman or in the “Shot in the Dark” music video, it’s hard to believe so many people were afraid of him.

The body of work he created is versatile enough to be loved by glam rockers, grunge musicians, punks, thrashers, and the alternative nation, making him a rare artist to thrive across multiple generations. Rappers liked him enough for sampling (Trick Daddy’s hit “Let’s Go” riffs on “Crazy Train”) and collaboration (from “For Heaven’s Sake 2000” with the Wu-Tang Clan through “Take What You Want” with Post Malone and Travis Scott, giving the septuagenarian his greatest Billboard success in three decades).

But while Ozzy updated his sound with new levels of heaviness (special thanks to first mate guitarist Zakk Wylde, who’s performed on Ozzy’s best work since the ‘90s), and expanded his range as a singer (the lovely “Mama, I’m Coming Home,” a song few of Ozzy’s peers could have pulled off, is as enduring as anything he recorded), he didn’t chase trends. He maintained his older fanbase but never stopped drawing in young fans. Nobody questioned Ozzy’s ability to headline over the mightiest thrash, doom, death, and black metal bands of his day, not to mention the nu-metal and rap-rock trends he outlasted. Anyone with a passing interest in metal can impersonate Ozzy’s garbled, f-bomb-heavy stage banter, offset by jumping and clapping, or the hunched, stalking, variation he adopted when his body started slowing down, like a heavy metal Crypt-Keeper inviting listeners in for a story. Ozzy wasn’t always a sober or coherent performer, but he was always magnetic, and the last time I saw him (2016 at Madison Square Garden, one of two sold-out nights) he was transcendent.

The world has been catching up to Ozzy. After years of only making rare appearances on rock radio, he’s almost ubiquitous on classic rock and metal playlists, not to mention athletic events and movie soundtracks. A few seconds of Ozzy could be the best scene of a bad movie (his “Jerky Boys” and “Little Nicky” cameos are worth a YouTube search), or the best line of a good movie (his priceless delivery in “Private Parts”).

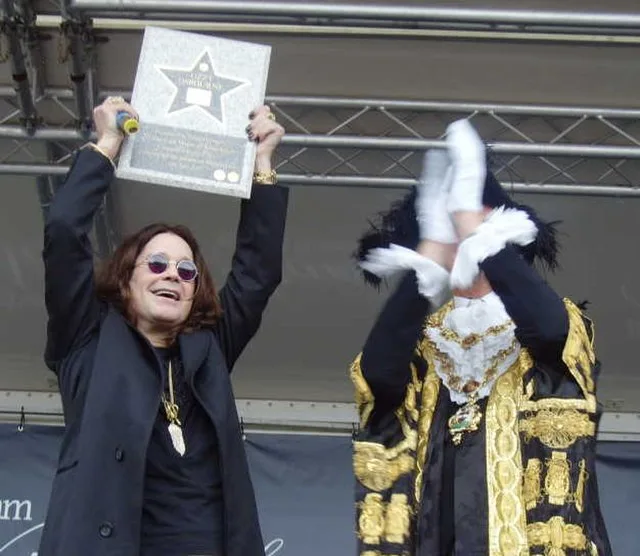

His Rock Hall induction, with an impassioned speech by Jack Black and performers ranging from Billy Idol to Maynard James Keenan to Jelly Roll, didn’t occur until last October. On July 5, 2025, seventeen days before his passing, Ozzy and Black Sabbath headlined the highest-grossing charity concert to date, raising over $190 million for Cure Parkinson’s, Birmingham Children’s Hospital, and Acorn Children’s Hospice, (inspiring some to point out that Ozzy has always been a more generous humanitarian than any of his religious right adversaries), packed with the greatest all-star metal lineup ever assembled, including Metallica, Guns N’ Roses, Slayer, Pantera, Tool, Gojira, Lamb of God, and Mastodon. At the end of the sold-out stadium show, Ozzy looks awestruck, as if he still can’t believe all this is happening to him. For someone who supposedly had seen and done it all, it’s not hard to see the misfit Brummie up on stage, still processing ten hours of tributes from some of the world’s biggest metal bands, while he’s handed a cake and watches fireworks go off in his honor.

I met Ozzy once. I was interning at a radio show where he was being interviewed, and I begged for a chance to give Ozzy his waiver to sign. Ozzy’s handler was firm with me: I was not to talk to, acknowledge, look at, or breathe near Ozzy, unless Sharon was in the room. I understood.

Sharon and Ozzy arrived together, and Ozzy sat peacefully in a chair while Sharon schmoozed. Sharon was delightful (when we didn’t have the drink she asked for she happily took a substitute) and signed her waiver, no problem. But when I turned to Ozzy with his waiver, Sharon walked out of the room.

I never found out if Sharon left because she didn’t care about the handler, or because she knew it’d make me euphoric to have a moment alone with Ozzy Osbourne. I can’t remember what I gushed to him about for 30 seconds (what does one even say to the Prince of Darkness? Shouldn’t we be kneeling?). But I’ll always feel blessed that he took a moment to peer out from behind his purple-tinted sunglasses and gently offer me a handshake. “Thank you,” said Ozzy.

A minute later, I watched Ozzy cackle and raise his arms when the DJ introduced him. There he was.

Thank you, Ozzy.

Ben Apatoff is the author of Body Count (33⅓) and Metallica: The $24.95 Book, two books about bands that frequently cite Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath’s influence. Order Body Count (33 ⅓) from Bloomsbury here.