Last year, the REELZ cable channel rolled out an extensive series of

programming called “The Kennedy Files.” It seemed to leave no stone

unturned: John F. Kennedy’s hidden health problems, drug use and extramarital

sex life, the tragedies in the Kennedys’ family life, even the further extremes

of conspiracy theories about his assassination. I guess one shouldn’t expect

much from a cable channel whose signature program is “Autopsy,” a

revisionist look at celebrity deaths (including people who obviously died of

gunshots or drug overdoses), but “The Kennedy Files” seemed to miss

the point. Examinations of the Kennedys’ politics took a back seat to their

charisma. French philosopher Guy Debord, who coined the phrase “the

society of the spectacle,” would have had a field day. Yet John F.

Kennedy’s appeal lives on, 53 years after his death. That’s not the least of

the lessons taught by Criterion’s new set of four documentaries about him: “The Kennedy Films of Robert Drew & Associates.”

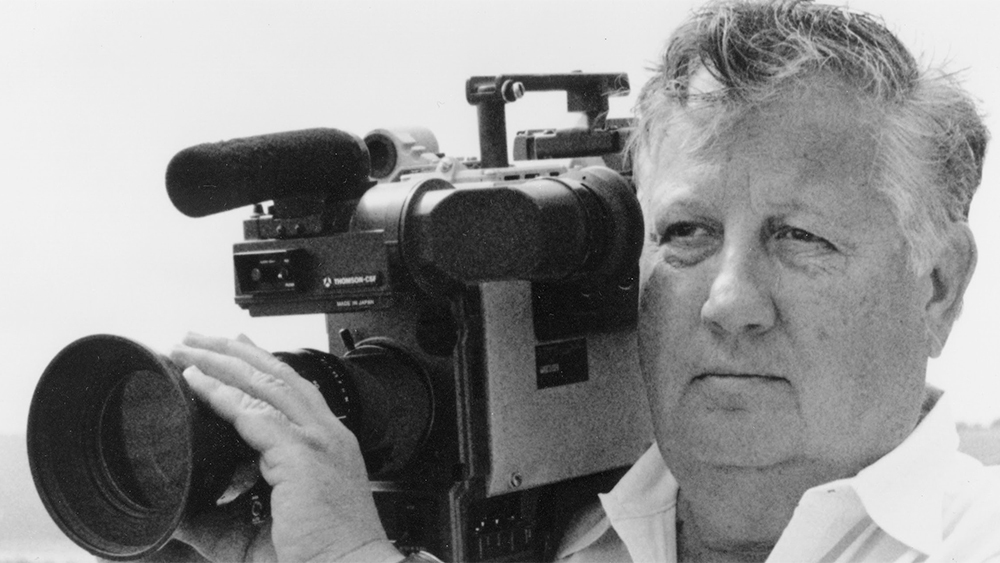

“The Kennedy Films of Robert Drew & Associates” is as interesting historically as

aesthetically, and not just for those fascinated by the Kennedys. While

“Primary,” “Adventures on the New Frontier” and

“Crisis” all include voice-over, they point the way towards the

direct cinema documentaries that would dominate the ’60s. One senses that these

films, particularly “Adventures on the New Frontier,” are often

limited by their TV funding and roots in the Time-Life aesthetic, yet Drew

managed to create something new from these unpromising sources. Additionally,

it’s worth pointing out that Criterion has outdone itself with extras this time

around. I’m sure this is the first time former Attorney General Eric Holder has

appeared on a Criterion disc (to comment on “Crisis”). Drew, Leacock

and Pennebaker offer commentary on a shorter, alternate version of

“Primary.” The four main documentaries only add up to three hours,

but it’s an immersion in a history that shaped our present, including the

election primaries now underway.

“Primary” has no directorial credit, but Richard Leacock,

Robert Drew, Albert Maysles and D.A. Pennebaker all worked on it. Although it’s an American nonfiction film, its raw quality marks it as a contemporary of the French New Wave, filled with startlingly

tight close-ups that are the result of lightweight 16mm cameras (personally designed by Drew and Leacock) which allowed the cameramen to

get extremely close to their subjects. Shot over the course of five days as Hubert Humphrey and John

F. Kennedy battled for the 1960 Democratic nomination in Wisconsin, “Primary” shows a

recognizable but very different America from the one we live in. For one thing,

children and young teenagers take an interest in politics. On a more serious

level, the film feels pre-civil rights; I don’t think a single person of color

appears in it. Drew and co. seem as interested in how it feels to run for president as in what Humphrey and Kennedy plan to do in office. Humphrey does

get to talk for several minutes about his agricultural policy, but he starts

off bashing the East Coast media. (You can see echoes of Ted Cruz’s dig at “New

York values” here.) Even from a distance of 56 years, Kennedy’s glamour cuts

through. Most of the audiences to whom he speaks look rather dowdy in

comparison, as does Humphrey. Their televised debate is about stardom versus

policy. History tells us which won.

The 1961 “Adventures on the New Frontier” begins by recycling

footage from “Primary.” It reprises the story of Kennedy’s primary win over

Humphrey, going on to depict Kennedy’s sweep into the White House. Made for

ABC, it reflects Kennedy’s own enthusiasm for “Primary”; the President gave Drew

and his team access to the White House and his staff. However, “Adventures on

the New Frontier” tends towards the hagiographic, far more than its precursor.

That access came with a cost. As a result, the most interesting scenes in

“Adventures of the New Frontier” abandon Kennedy altogether. Depicting the

President’s concern about economic recession, the filmmakers traveled to West

Virginia and found a community devastated by the closure of its local mine.

They talked to a former miner who has now been unemployed for six years and

whose three-year-old daughter is hospitalized with malnutrition. On the other

side of the world, Drew filmed Governor Williams’ trip to a UN-sponsored

economic summit in Addis Abba, Ethiopia. There, he found the rebellious spirit

of the ‘60s getting underway. A representative from Guinea protests the

suggestion that Africans speak in French. Signs of the Cold War are everywhere:

Russian classes are taught in Ethiopia, under photos of Lenin. Naturally,

Kennedy established English classes, under his photo. Gov. Williams got in

trouble in this trip for declaring “Africa for the Africans,” but even this

mild anti-colonial statement is a recognition of the zeitgeist.

Drew maintained a friendly relationship with Kennedy but waited two

years for another opportunity to film him in action. Despite its title, the

1963 “Crisis” is not about the Cuban Missile Crisis. Instead, it’s about the

integration of the University of Alabama. Despite ending with a televised

Kennedy speech, it’s the least worshipful film in this set, showing the

President weighing the possible political costs of wholeheartedly embracing

integration. His rival is Alabama Governor George Wallace, who gets quite a bit

of screen time, as do the two African-American students trying to register at

the college. Here, Drew tones down the heavy-handed voice-over that marred

“Adventures on the New Frontier” and assumes spectators can figure out what’s

going on for themselves. It lives up to the promise of the other two features included

here, taking us behind the scenes of a moment of realpolitik. The results are

no less suspenseful because all Americans know the eventual outcome. “Crisis”

is the strongest film in this set.

Abraham Zapruder’s film of Kennedy’s assassination is the structuring

absence of this set. In its place, we have the 13-minute 1964 short “Faces of

November,” made shortly after his death. It’s a dignified depiction of

Kennedy’s funeral. Drew tried to make the country’s grief a part of the film

itself, most bluntly by refusing to include speech in “Faces of November.”

There’s sound here—including plenty of funereal music—but no words. As in

“Primary,” he gets very close to his subjects’ faces; in fact, it’s remarkable

that mourners would be so blasé about having a movie camera shoved near them.

He managed to capture remarkable images of grief, including military men

breaking down in tears for Kennedy. This is the flipside of the late

President’s glamour, the society of the real.