“Lives Worth Living” premieres on the PBS series “Independent Lens” on October 27th at 10:00 p.m. (ET/PT). For more information, visit the film’s PBS website and filmmaker Eric Neudel’s website.

To be disabled in America, in 2011, is to occupy the midpoint of a metaphorical highway, some stretches smooth and evenly paved, others rocky and difficult to navigate. When you look back at the road behind, you feel proud and satisfied that people with disabilities (PWD) have made significant progress since the days when we had no voice, no place in society, no civil rights whatsoever. Looking ahead, you see fewer physical obstacles but other remaining barriers, in terms of backward attitudes and ongoing exclusion, that society is still stubbornly reluctant to remove.

Like those of us with disabilities, Eric Neudel’s documentary “Lives Worth Living” is situated at that halfway point on the rocky road of progress. In just 54 inspiring and informative minutes, Neudel’s exceptional film (airing Oct. 27th at 10pm on the PBS series “Independent Lens”) provides a concise primer on the history of the disability rights movement in America. The film culminates with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush on July 26th, 1990.

And yet, it’s only half the story. In a perfect world, PBS would immediately finance a sequel so Neudel (who has devoted his career to documenting political and civil rights struggles) could chronicle the first 20 years of the ADA. That history is still unfolding, and the struggle to enforce and fully implement the ADA is just as compelling as the struggle for disability rights throughout the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s.

(I’ll go a step further and say that the subject is worthy of a multi-part Ken Burns approach, echoing the sentiment of veteran disability-rights advocate Lex Frieden, who observes in “Lives Worth Living” that “If you have a good story to tell, it’s not hard to get people to watch or listen to it.” And the tale of pre- and post-ADA disability in America is a very good story indeed, as packed with human drama as any other fight for equality in all of American history.)

When “Bush 41” signed the ADA into law on that sunny afternoon in 1990, the occasion drew what is still the largest audience that has ever assembled for a bill-signing on the south lawn of the White House. There were nearly 4,000 people gathered that day, many of them PWD who made extra effort to be there.

At the time, I had just turned 29 and I’d been disabled (C-5/6 quadriplegia) for 11 years, since a diving accident on the coast of Maui in 1979, two weeks after high-school graduation and three weeks before my 18th birthday. Those 11 years had given me enough perspective to deeply appreciate the ADA, but to be perfectly honest, disability advocacy was not my cup of tea. Since the mid-’80s I’d been focused on establishing a mainstream career and supporting progress (what little there was of it) toward curing paralysis caused by spinal cord injuries. I never denied the physical and social reality of my disability, but I had yet to be awakened to the urgency of disability-rights advocacy and the history that led to the passage of the ADA.

That’s why “Lives Worth Living” is so badly needed as an introduction to disability rights history. It’s the first film of its kind (ponder that for a moment) and while it may not attract a large able-bodied audience (although it should), it provides long-overdue acknowledgement that this is an American story worth telling — a story that has remained untold, in the mainstream media, for far too long. For anyone who’s unaware of the people who pioneered the disability rights movement in America, Neudel’s film offers a joyous opportunity to celebrate the triumphant achievements of unsung American heroes.

One of those heroes is Fred Fay, Ph.D., who died last August 20th (and to whom “Lives Worth Living” is dedicated). Like me, Fred was paralyzed at age 17, but that was in 1961, when disability activism was still in its barely-noticed infancy. Fifty years later, Fay appears emaciated in his final months of life but still full of fighting spirit, expertly navigating his motorized gurney-bed (!) around his fully-accessible home as he recalls a time when the words “disability” and “rights” were considered virtually incompatible, if they were considered at all. As Illinois-based disability rights pioneer Ann Ford observes, it wasn’t until thousands of wounded soldiers returned from World War II that disability-related issues gained any recognition.

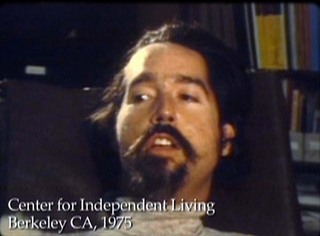

Fay was determined to live the life he chose for himself, not the strictly regimented life of neglect and hopelessness in institutions that had historically relegated the disabled to a hidden, powerless existence. Fay and a small group of dedicated activists spearheaded the nascent disability rights movement. They paved the way for tenacious, pioneering activists like Ed Roberts, who founded the independent living movement in Berkeley, California, in the wake of pre-ADA milestones like the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 (the first disability-rights law, weakened by lack of enforcement) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which was initially vetoed and then signed under pressure by president Richard M. Nixon. (Even then, change was slow in coming; four years later, the specified regulations for the Rehab Act still hadn’t been signed into law.)

Another hero is Judy Heumann, who appears throughout “Lives Worth Living” in archival footage and a present-day interview. With fierce intelligence and gracefully eloquent authority, Heumann appeared at nearly every major pre-ADA protest, becoming one of the most persuasive and forceful speakers of truth to power. We see her at one event, overcome with emotion as she defiantly berates a government official for displaying ignorant condescension (a constant problem in disability-rights advocacy) toward her and, by extension, the entire disabled population.

With straightforward chronology, “Lives Worth Living” covers all of the major milestones leading up to the passage of the ADA. Perhaps the most significant pre-ADA protest (or at least the most historically pivotal) was the “Deaf President Now” (DPN) movement that rose to triumph at Gallaudet University in 1988. Located in Washington, D.C., Gallaudet is (to quote its website) “the world leader in liberal education and career development for deaf and hard of hearing students.”

In 1988 (two years after the 124-year-old college was granted university status), students, faculty and staff demanded that the time had come for a deaf person to run the university. When deaf candidate I. King Jordan was elected as Gallaudet’s president after the sensible resignation of hearing appointee Elizabeth Zinser, the “DPN” triumph made international headlines and spurred discussion about the broad spectrum of disability issues that ultimately led to the creation and passage of the ADA.

Jordan joins the roster of heroes in “Lives Worth Living,” and when he recalls his feelings of joy and pride on the day Bush 41 signed the ADA into law, it’s one of the most uplifting moments in the film. I’m not ashamed to admit that I got choked-up and misty-eyed when Jordan described the definition of “Pah,” the American Sign Language symbol used to express a long-awaited moment of success or achievement. “That was a ‘Pah’ day,” Jordan says (and signs) with a warm smile, “the day that you guys [the able-bodied] saw us as your peers, and not as [people] who needed your help.”

As the former director of Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living (CIL), Michael Winter has a similar, more humorous recollection of the amazing day when hundreds of disabled activists crawled and climbed up the capitol steps in Washington D.C. to protest the slow process of ADA approval. In archival news video we see a young girl with cerebral palsy, fiercely determined to reach the top (“I’ll take all NIGHT if I have to!”), inspiring the admittedly out-of-shape Winter to follow close behind.

When the activists gathered en masse in the capitol rotunda, Winter was approached by a young, able-bodied woman who was excited by the crowd. Turns out she was a tour guide, expecting to host a group of “handicapped” people on a tour through the capitol.

“I have to tell you something,” Winter wryly informed her. “I don’t think these people are here for a tour.”

As New Mobility magazine editor Tim Gilmer notes in his recent review of “Lives Worth Living,” the film is “bursting with righteous indignation,” not only among the thousands disability rights advocates whose protests led to the ADA, but also among the ADA’s most ardent supporters in government, including Sen. Tom Harkin (D. – Iowa) and Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D. – Mass.), whose sister Rosemary was developmentally disabled, and whose entire family (most notably through the creation and ongoing support of the Special Olympics) played a major role in promoting the rights of PWD.

Then there is the late Justin Dart, Jr., whom Marca Bristo (president and CEO of the Chicago-based advocacy group Access Living) describes as “our beloved spiritual leader.” As Judy Heumann correctly notes, Dart didn’t pioneer the disability rights movement, and as the privileged son of a prominent Republican businessman (Walgreens executive Justin Dart, Sr.), he hadn’t experienced the kind of virulent discrimination that most PWD had endured throughout pre-ADA history. But because his father was a member of Ronald Reagan’s “kitchen cabinet” in the ’80s, Dart Jr. was acutely aware of the vagaries of the political process, and capable (as Judy Heumann recalls) of learning and then articulating disability issues and “gathering support from a very broad set of constituencies.”

I could happily continue to sing the praises of the many other veteran disability advocates who appear in “Lives Worth Living” (including the irreverent Bob Kafka, whom I am proud to count among my Facebook friends), but their words and actions are best discovered by viewing the film. Their inclusion qualifies as long-overdue recognition that they were (and are) righteous soldiers in a battle that has largely been waged beyond the purview of the mainstream media.

All of which brings us to the present state of affairs, which many disabled people (myself included) find sorely disappointing. It’s now been 21 years since the ADA has resulted in broad, substantial improvements for American PWD, but society at large — including a startling number of disabled people — still doesn’t seem to grasp its significance.

Ignorance and indifference continue to be the ADA’s societal ball and chain. When the 20th anniversary of the ADA was celebrated in July of last year, it barely caused a ripple in the mainstream. I’ve been disabled for 32 years now, and like most PWD who care about the future, I fully understood why the question was asked (in the July 2010 cover story of New Mobility and elsewhere) whether the “ADA glass” is half empty, half full, or both.

That question still needs to be asked because if you’re disabled in America, in 2011, you frequently feel stuck along that metaphorical highway of progress. Many of us sit there, waiting impatiently for society to catch up with us and move us forward in unison. As Judy Heumann correctly observes in “Lives Worth Living,” a few acts of legislation won’t remove the discrimination that the ADA was designed to legally eliminate. To be disabled in America, in 2011, is to realize that you may have gained your civil rights, but most of society didn’t get the memo.

Consider the following:

● In 99.9% of the mainstream news coverage related to our current economic meltdown, there hasn’t been any substantial reporting of the fact the PWD are facing the worst employment crisis in their perpetually under-employed history.

● The immensely popular TV series “Glee” was conceived to promote diversity and acceptance of differences in high school and society at large, yet its casting director tried and failed to find an authentically disabled actor to play Artie, the paraplegic teenager played so appealingly by able-bodied actor Kevin McHale. This didn’t happen because the right disabled performer doesn’t exist (trust me, he’s out there somewhere), but because decades of ignorance and indifference have resulted in the ongoing exclusion of PWD in Hollywood. Now McHale has to endure legitimate charges of “faking it” while authentic PWD (who are now recognized by Hollywood’s annual Media Access Awards) continue to make slow but steady progress toward full inclusion in the entertainment industry.

● The best-known and most successful documentary about disabled people is 2005’s Oscar-nominated “Murderball“, a well-made and deservedly popular real-life “quad-rugby” drama that nevertheless makes no mention of the ADA while reinforcing society’s apparently persistent need to embrace the stereotypical image of “inspirational cripples.” (And while Christopher Reeve played a similar “Super Quad” role on every stage from “Oprah” to the Oscars, he realized, before his death, that his celebrity could be channeled to promote a more substantial and wide-ranging awareness of disability issues.)

● On a related note, take a casual look at the sets for talk shows, awards ceremonies and game shows: Few if any are specifically designed to accommodate wheelchairs, reflecting decades of exclusion, arguably benign (because nobody “intends” to discriminate) but still stubbornly pervasive.

● Many able-bodied people expressed “end-of-an-era” disappointment when long-time host Jerry Lewis was excluded from this year’s annual Labor Day telethon to benefit Lewis’s lifelong cause, the Muscular Dystrophy Association. But what the MDA and the mainstream media didn’t say publicly was that Lewis (who’d already gained a dubious reputation as a notorious loudmouth) had become a public relations nightmare by perpetuating his own outmoded insistence that pity and institutionalized support were still the best way to “treat” the disabled. As MDA officials rightly realized, Lewis and his regressive old-school attitude had become an embarrassment that they needed to avoid.

● In March of this year, 91-year-old Republican representative Martin Harty, of New Hampshire, recklessly joked that all of his state’s developmentally disabled and mentally ill residents were “defective people” who “should be shipped to Siberia.” After initially refusing to apologize for his insensitive wisecrack, the freshman lawmaker resigned and said he was sorry that his “big mouth caused this furor.” He may have been joking in public, but he was expressing a still-common sentiment that remains dangerously private: Many able-bodied people continue to condescendingly and mistakenly perceive the disabled as needy, an expendable drain on the economy and therefore “better off dead.” And so…

● Even if the title of “Lives Worth Living” is not specifically intended as a rebuttal to the “quad euthanasia” uproar caused by the Oscar-winning drama “Million Dollar Baby“, it’s guaranteed that many PWD will interpret it as such. When I interviewed director Clint Eastwood about the controversy for New Mobility in early 2005, he emphasized that his film was never intended to suggest that people with disabilities are better off dead. After meeting Eastwood (and — full disclosure — having occasionally benefitted from his kindness), I fully accept his response as sincere, just as Eastwood – and Neudel – must understand that all films carry potential interpretations (like the suggestion that disabled people are “better off dead”) that exist beyond their makers’ intentions.

You get the point, and it’s not my intention to focus on stubborn social drawbacks. I’ve experienced enough discrimination (both subtle and explicit) to know that the victories celebrated in “Lives Worth Living” represent permanent and positive change that will continue to resonate and deepen as our society (hopefully) continues to mature and accept PWD as vital, contributing members of society.

I also know what Justin Dart, Jr. knew — and this is another important point made in “Lives Worth Living”: People with disabilities have an equal responsibility to educate themselves about the issues that affect them, and then advocate on their own behalf.

Historically, adult PWD have often been condescendingly dismissed as “big children,” incapable of representing themselves in the process of government. By showing how PWD took control of their lives and forced the ADA into law, “Lives Worth Living” exposes the ignorance of that perception. It’s not a perfect film; Neudel takes it for granted that viewers will know what “CIL” stands for [Centers for Independent Living], and its single-hour length prevents it from delving deeply into the post-ADA hardships that PWD continue to cope with. Still, Neudel is himself a pioneer, and in its own unassuming fashion, his film is nothing less than groundbreaking.

It’s taken decades of effort for PWD to get where we are, and the best way to know where we’re going is to remember where we’ve been. It’s easy to forget, 21 years later, that the ADA (like all civil rights legislation), was initially met with suspicion, fear and ignorant, misleading backlash. Some of that resistance continues today; it’s just more insidious.

I still cringe when I think about the many times, in the early ’90s, that TV journalist John Stossel abused his power as an ABC reporter by broadcasting numerous reports (with tacit network approval) intended to smear the ADA and distort its noble purpose. Stossel (who now works for Fox News) was far from alone in his ignorance, but his reports were the most conspicuous and — this was the hard part — they were widely accepted as accurate.

Stossel’s ignorance is reflected in another uplifting highlight in “Lives Worth Living”: It was 1989, and Tony Coelho (House Majority Whip, 1986-89) ran into a roadblock when Bush 41’s Chief of Staff, John Sununu, steadfastly opposed the ADA and refused to sign off on the bill. Shortly thereafter, ADA champion Harkin attended a meeting in the capitol building. Harkin, Ted Kennedy and Kennedy staff attorney Bobby Silverstein were seated on one side of a conference room table, and Sununu sat alone on the other. At one point in the meeting, Sununu started yelling his objections at Silverstein and belittling the attorney, a devoted ADA advocate, as a Kennedy underling. As Harkin recalls:

“Kennedy stands up, threw his chair back, leaned across the table, slapped his hand down on the table loud enough to be heard halfway across the capitol [and] pointed his finger right in Sununu’s face and said ‘You don’t yell at our staff. [If] you want to yell at someone, yell at me! Don’t you ever yell at a member of my staff in my presence!’ Sununu just went pale. The blood just drained from his face. Kennedy’s veins were popping out of his neck…I thought he was gonna grab [Sununu] by the throat! And all of the sudden, John Sununu became… irrelevant.”

Now, whenever I despair over the still-disadvantaged position of PWD in America, I will fondly recall Harkin’s anecdote and the fury of Kennedy, who (as Gilmer notes in his New Mobility editorial) had the full weight of his family history behind him. Because now I know, 21 years after the ADA’s passage, that anyone who publicly tries to oppose or weaken the ADA will instantly become irrelevant.

And that, my friends, is progress.

Watch Like an Emancipation Proclamation for the Disabled on PBS. See more from Independent Lens.

<iframe width="512" height="377" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/fOWFm_DV_DY?rel=0" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="“>

_ _ _ _ _

A Seattle-based freelancer, Jeff Shannon has been writing about film and filmmakers since 1985, for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (1985-92) and The Seattle Times (1992-present). He was the assistant editor of Microsoft’s “Cinemania” CD-ROM and website (1992-98), where he worked with rogerebert.com editor Jim Emerson, and was an original member of the DVD & Video editorial staff at Amazon.com (1998-2001). Disabled by a spinal cord injury since 1979 (C-5/6 quadriplegia), he occasionally contributes disability-related articles to New Mobility magazine, and is presently serving his second term on the Washington State Governor’s Committee on Disability Issues and Employment.