“American Experience: Billy the Kid” is available on demand at PBS.org after its January 10 broadcast at 9 p.m. (ET/PT). Check local listings.

Who hasn’t heard of Billy the Kid? He’s often portrayed in Westerns — sometimes as a blood-thirsty killer — but the PBS “American Experience” documentary “Billy the Kid” gives us a sympathetic portrayal of an orphan who “became the most wanted man of the west.” Instead of drama, blood, and lust in the dust, you’ll get a more multicultural view of a homeless kid gone wrong after being wronged.

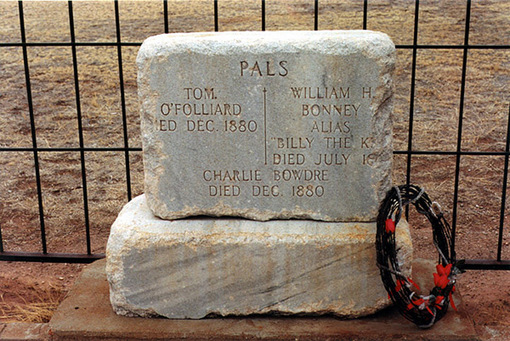

The one-hour film, narrated by Michael Murphy, begins with a hangman’s noose. The date is April 28, 1881 and the 21-year-old man known as Billy the Kid is in the custody of Sheriff Pat Garrett. He escapes his appointment with the hangman, but he won’t be alive much longer.

Born in New York City, he was originally known as Henry McCarty, the son of poor Irish immigrants. His widowed mother, Catherine, along with Henry and his younger brother, Joseph, headed West first to Indiana in 1868 and then, with her new husband William Antrim, to New Mexico. New Mexico was the destination for silver prospectors, and William, in his search for a silvery jackpot, was an absentee husband and stepfather.

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo after the Mexican-American War gave the Southwest and California to the United States and by 1850 the New Mexico Territory was established. Americans and new immigrants began flooding into the area that is now New Mexico, taking the land away from the Latino ranchers and sheep farmers.

When Catherine died in 1874, Henry and his brother were separated and abandoned by their stepfather. Consider how a young lad of 15 might survive, homeless, without family and no means of work. Henry was not tall and his build was slight. Think of Oliver looking for his Artful Dodger in the Southwestern desert instead of London. Henry learned how to steal horses and, most importantly, how to use a six-shooter to defend himself, because even then bullies abounded. About this time, he adopted the alias William Bonney and went by Billy.

In Lincoln County, NM, two Irish immigrants, Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan, were establishing their own kingdom by cattle ranching and through their mercantile and banking enterprises. Because they had no competition, they could gouge the local farmers and ranchers. Into this Irish stronghold comes a young wealthy Englishman, John Tunstall, who also means to establish a cattle ranch and a competitive banking and dry goods businesses.

There’s a suggestion that the tensions from Great Britain between the Irish and the English came into play here. In any case, Murphy and Dolan arrange to have the 24-year-old Turnstall killed in 1878. Turnstall’s cowboys, including Billy, want revenge, and calling themselves the Regulators, they begin the Lincoln County War.

Director John Maggio quickly whisks us through history, drawing on lively interviews with several historians and writers, many of whom have written books on Billy the Kid. The former governor of New Mexico, Bill Richardson, who once considered giving Billy the Kid a posthumous pardon, also weighs in.

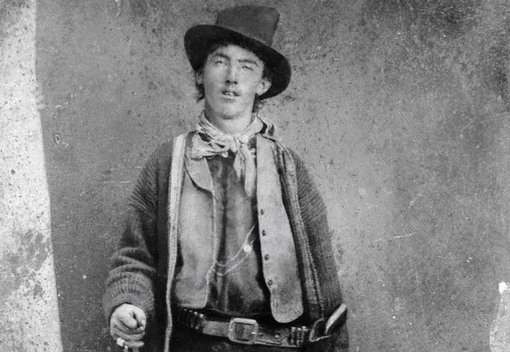

You might get tired of seeing that one photo of Billy the Kid (at the top of this page), but it is the only authenticated image of him and probably one of the priciest pieces of Western memorabilia. Just this last year, William Koch, a Florida energy tycoon, paid $2.3 million for that tintype at auction.

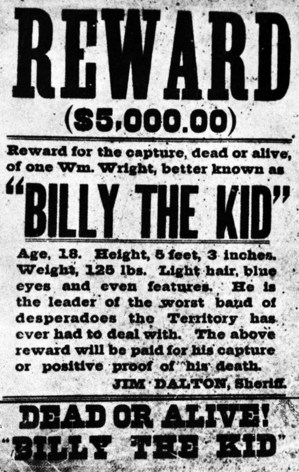

In this one-hour program, we get a lot to consider, enough to make us re-think some old classic movies although the program itself doesn’t touch on Hollywood’s Billy the Kid. Consider: “Billy the Kid” displays a wanted poster that describes Billy as 125 lbs. and only 5 foot 3. (At his death, in July 1881, Billy was about 5 foot 8.)

When the 33-year-old Paul Newman played Billy the Kid in director Arthur Penn’s “The Left Handed Gun,” Newman was older, and taller, than Billy ever got to be — and Billy wasn’t left-handed. That was a myth created by the mirror image tintype. Billy did have blue eyes.

In Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid,” singer Kris Kristofferson was 37 and a few inches taller than Billy the Kid. The white-haired James Coburn was 45 when he played Pat Garrett but when Garrett killed Billy in 1881, Garrett was 31 and dark haired. The movie is somber, gruesome and elegiac. Although Roger Ebert dismissed it, Peckinpah’s film (particularly in its restored 1988 director’s cut) has its ardent fans.

Christopher Cain’s 1988 Brat Pack western, “Young Guns,” was actually a closer retelling of the Lincoln County War. Emilio Estevez, as Billy, was 26 — just a few years older than Billy when he died, and at 5 foot 6, he more closely fits the wanted poster description. Yet writer John Fusco took a few liberties with history, or what we know of history. For instance, Tunstall is played as a fatherly figure when the PBS documentary reveals he was a dashing young man and not 50 as Terence Stamp was.

Estevez portrays Billy as a laughing almost psychotic wild boy, a portrayal he repeated in the 1990 “Young Guns II.” Why else would Billy remain in New Mexico instead of fleeing across the border to Mexico? “Billy the Kid” forwards another possibility that makes Billy a romantic, tragic figure.

Throughout, the documentary indicates Billy was well-liked, particularly among the Latino population. There’s evidence that, given the chance, he wanted to earn an honest living and have a stable life. Yet he was bullied and finally beaten when he was betrayed.

Watch Billy the Kid Chapter 1 on PBS. See more from American Experience.

Watch Billy the Kid Ballad on PBS. See more from American Experience.

Jana J. Monji is a Los Angeles freelance writer for the arts who almost always would rather be dancing Argentine tango or East Coast swing than sitting down. She has written for the Los Angeles Times and LA Weekly and currently writes for the Pasadena Weekly and Examiner.com on theater, art, dance. To combat the Los Angeles ailment of road rage, she takes a hammer and torch to metal to make jewelry.