Excellent op-ed piece by philosophy prof Tom Dodd Todd May in the New York Times (“Happy Ending“) about the ending of “No Country For Old Men“:

The harm of death goes to the heart of who we are as human beings. We are, in essence, forward-looking creatures. We create our lives prospectively. We build relationships, careers, and projects that are not solely of the moment but that have a future in our vision of them. One of the reasons Eastern philosophies have developed techniques to train us to be in the moment is that that is not our natural state. We are pulled toward the future, and see the meaning of what we do now in its light.

Death extinguishes that light. And because we know that we will die, and yet we don’t know when, the darkness that is ultimately ahead of each of us is with us at every moment. There is, we might say, a tunnel at the end of this light. And since we are creatures of the future, the darkness of death offends us in our very being. We may come to terms with it when we grow old, but unless our lives have become a burden to us coming to terms is the best we can hope for.

OK, it’s not explicitly about “NCFOM,” but it is quite clearly about what “NCFOM” is about: living life with a vision of the past and a “pre-visioning” of “what’s coming,” the only certainty being the knowledge of certain death. Where or when or how, we don’t know. Just that it’s out there, where the old-timers have gone before us, in all that cold and all that dark.

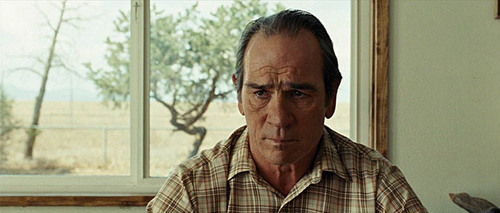

Retired sherrif Ed Tom Bell, sitting with his wife one morning in his pretty kitchen, surrounded by acres of hard country and facing the prospect of the day ahead, recounts two dreams from the night before. The only other sound is the ticking of a clock:

Both had my father. It’s peculiar. I’m older now’n he ever was by twenty years. So in a sense he’s the younger man. Anyway, first one I don’t remember so well but it was about money and I think I lost it.

The second one, it was like we was both back in older times and I was on horseback goin through the mountains of a night, goin through this pass in the mountains. It was cold and snowin, hard ridin. Hard country. He rode past me and kept on goin. Never said nothin goin by. He just rode on past and he had his blanket wrapped around him and his head down, and when he rode past I seen he was carryin fire in a horn the way people used to do and I could see the horn from the light inside of it. About the color of the moon. And in the dream I knew that he was goin on ahead and that he was fixin to make a fire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold, and I knew that whenever I got there he would be there. Out there up ahead.

And then I woke up.

May writes:

I prefer to think that the paradox of death is the source not of despair but instead of the limited hope that is allotted to us as human beings. We cannot live forever, to be sure, but neither would we want to. We ought not to mind the fact that we will die, although we really would rather that it not be today. Probably not tomorrow either. But it is precisely because we cannot control when we will die, and know only that we will, that we can look upon our lives with the seriousness they merit. Death takes away from us no more than it has conferred: lives whose significance lies in the fact they are not always with us.

Our happiness lies in being able to inhabit that fact.