Until the day he died, I always called him “Daddy.” He was Walter Harry Ebert, born in Urbana in 1902 of parents who had emmigrated from Germany. His father, Joseph, was a machinist working for the Peoria & Eastern Railway, known as the Big Four. Daddy would take me out to the Roundhouse on the north side of town to watch the big turntables turning steam engines around. In our kitchen, he always used a knife “your grandfather made from a single piece of steel.”

Gogi Grant, when she was nearly 80, singing “The Way Wayward Wind.”

I never met my grandparents, and that knife is the only thing of theirs I own. Once when I was visiting my parents’ graves, I wandered over to my grandparents’ graves, where we’d often left flowers on Memorial Day. I realized consciously for the first time, although I must have been told, that my grandfather was named Joseph. My middle name.

What have I inherited from those Germans who came to the new land? A group of sayings, often repeated by my father: If the job is worth doing, it’s worth doing right. A good woodsman respects his tools. They spoke German at home until the United States entered World War One. Then they never spoke it again. Earlier than that, he was taken out of the Lutheran school and sent to public school, “to learn to speak American.” He spoke no German, apart from a few words.

There is a story he told many times, always with great laughter. It was from Joseph. Before a man left Germany for America, the school master taught him to say “apple pie” and “coffee.” When he got off the boat, this man was hungry, and went into a restaurant. “Apple pie,” he said. The waiter asked, “Do you want anything on top? The man replied, “coffee!”

My father was raised in a two-story frame house with a big porch, on West Clark Street. His parents believed they couldn’t conceive, and adopted a daughter, Maud. Then they had three more children: Hulda, Wanda, and Walter. Aunt Maud and Uncle Ben lived north of Champaign in a house made of tar paper, heated by a stove. This was not considered living in poverty, but simply their home. It was always comfortable and warm, and I loved to visit. Uncle Ben drove a heating oil truck, and would sometimes drive past our house and wave. Always with a cigar stuck in his mug.

Hulda and Wanda remained at home. I spent hours with coloring books on their floor or at their kitchen table, and tiptoeing up and running down the scary staircase. They had an old ice box, and I got to put out the sign so the iceman could see from his wagon how much ice they needed. We sat around the kitchen table covered with oil cloth and ate beef and cabbage soup. Hulda contracted TB, and I heard, “She has to go live in the sanitarium up on Cunningham.” This was spoken like a death sentence. She died, and the body was laid out in the living room. I was allowed to approach her, and regarded her solemnly.

I regret I never knew Wanda as well as I did my uncles and aunts on my mother’s side. She worked most of her life as a saleswoman for the big G. C. Willis store in downtown Champaign, and we’d visit her there, my father always buying something. Everyone seemed to like her. The last time I saw her was in the 1970s, after she moved to a nursing home. My mother and I took her out to dinner. I enjoyed, and was a little surprised by, her warmth and humor. When I was a child she had seemed tall, spare and distant. “Your father’s initials are still carved in the concrete on the curb in front of the old house,” she told me. I went to look, and they were.

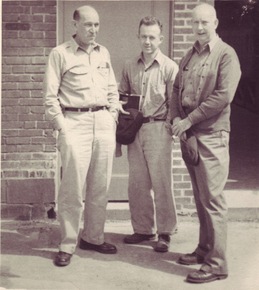

My father as a young man moved to West Palm Beach, Florida, and opened a florist shop with a man named Fairweather. “We delivered a lot of flowers to the Kennedys in their mansion,” he said, when Jack was elected President. There was a photo of him, trim and natty, standing beneath palm trees with a cigarette in his fingers. They lost the shop in the Depression and he had to move home to live. He apprenticed as an electrician at McClellan Electric on Main Street in Urbana, and then “got on” at the University of Illinois, where he worked for the rest of his life.

After the war, Bill and Betty Fairweather moved to Urbana, where Bill, the son of my father’s partner in the florist business, would study psychology. He’d been a bomber pilot, and later became famous in his field. Night after night, the voices of Bill and Walter and drifted in from the front porch, as they talked late and smoked cigarettes. In the 1980s, the Fairweathers came up to visit. “Rog,” he asked me, “did you ever wonder why a PhD candidate and an electrician would spend so much time talking? It was because your dad was the smartest man I ever met.”

Growing up, I always found books in the house. Daddy’s living room chair had a couple of bookcases behind it, including bestsellers like USA Confidential and matching volumes of Hugo, Maupassant, Chekhov, Twain and Poe. We took both Champaign-Urbana papers and the Chicago Daily News. He told me as soon as I learned to read that if I read Life magazine every week and the Reader’s Digest every month, I’d grow up to be a well-informed man. Every night at dinner we listened to Edward P. Morgan and the News, “brought to you by the thirteen and a half million men and women of the AFL-CIO.”

I was told, “the Democratic Party is the friend of the working man.” He was a member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, and my mother told me, “Your father may have to go on strike.” I pictured him consumed in flames and wept until it was all explained. To this day, I will not and cannot cross a picket line.

Walter was 37 when he married, 58 when he died. Of his earlier life I knew little, but one Sunday during the Rose Bowl Game the phone rang, and it was an old girl friend of “Wally” from Florida, who told my mother she’d found his number from information. My mother handed him the phone. There was ice in her eyes. After the call finished, I was told to go back downstairs and watch the game.

The TV set in the early days was banished to the basement, because my mother didn’t want it “cluttering up the living room.” Half of the basement held my father’s workbench, and the washer-wringer. The other half had been supplied with reclining aluminum deck chairs. Later there was room for my science fiction collection and a desk that represented the offices of the Ebert Stamp Company. Daddy and I faithfully watched Jack Benny, Herb Shriner on “Two for the Money,” Omnibus and particularly the Lawrence Welk Show. Welk reminded him of his father. When something good came on, my father would shout, “Bub, you’d better see this.” She was usually right upstairs at the kitchen table, reading the papers, listening to music on the radio. When she came down, she usually remained standing, as if she didn’t want the TV set to get any ideas. Otherwise she could have my chair, and I’d sit cross-legged on the floor.

My father woke up about 5:30 every morning. I’d hear him downstairs, taking clinkers out of the furnace and shoveling in coal. Then he’d turn on Paul Gibson from WBBM from Chicago. Gibson had no particular politics; he just talked for two or three hours, usually nonstop. Daddy would make coffee and toast, almost burnt, and the aromas would fill the small house. I’d stumble in and he’d hand me a slice, slathered with clover honey from the University Farms. Gibson didn’t play much music, but one day he played “The Wayward Wind” by Gogi Grant. I walked into the kitchen. “You like that?” my father asked, nodding. The song has haunted me ever after.

He spent a good deal of time tinkering with the house heating. In Reader’s Digest he read an article about the importance of humidity, and hung empty half-pound coffee cans by wires beneath the registers in every room. We’d fill them up with water from a coffee pot, poured down through the grating. “What if you don’t hit the can, Daddy?” “It will all come up sooner or later.” He’d hold his hand above a register “to see if the furnace is putting out.” Every autumn there was the exciting adventure of cleaning the furnace pipes of a year of dust, “so it doesn’t all blow back up and get your mother’s curtains dirty.” I would put on old jeans, a sweat shirt and swimming goggles, and crawl up the pipes with the extension hose on our Hoovermatic. By the time I grew too big for this task, we had “put in gas.”

He took me to see my first movie, the Marx Brothers in “A Day at the Races.” I had to stand to see the screen. Daddy laughing a lot. He had seen the real Marx Brothers in vaudeville at the Virginia in Champaign. We went to see “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” with me prepared to clap my hands over my eyes because Our Sunday Visitor said the movie was racy. Together we saw “Bwana Devil,” the first movie made in 3-D. And we saw Danny Kaye in “Hans Christian Anderson.” Oh, and Cleo Moore in something. She appeared at the screening, and I got her autograph. Those are the movies I remember us seeing together. My Aunt Martha took me to most of my movies.

At Walter’s lunch hour, he’d come home and fix himself something. His favorite meal was a peanut butter and jam sandwich and pickled herring in wine sauce. “The sweet and sour go against each other and make every bite fresh.” When he cooked at dinner, rarely, it was usually hamburgers, pressed on a device of his own manufacture, or round steak, sprinkled with Accent and flour, pounded with the side of a saucer, and fried. He made chili with some bacon in it, and let it improve in the refrigerator overnight. He always drew onion-chopping duty, with his father’s knife.

He’s play catch with me in the driveway. He took me hunting in Brown Woods with my BB gun and we found a dead fox and brought it home to show my mother. He’d take me to Illinois home games at Memorial Stadium. “See those electrical pipes? I installed them.” When the All-American J. C. Caroline broke away for a touchdown, he and everyone around us yelled so loudly it could be frightening. When it was very cold, he’d send me downstairs for ten-cent cans of hot chocolate, to hold in our pockets. In the cold air the smoke of his Luckies was sharp. Both my parents smoked. Everybody smoked. Ray Eliot, the legendary Illini coach, smoked on the sidelines during the games. After my father was told he had lung cancer, he switched to filter-tip Winstons.

Walter was a tall man for his generation, 6’2″. I never saw him angry with anyone except my mother, and their arguments were usually about money: How much they were helping her family, and how much they were helping his. Sometimes my mother would lie on my bed at night, sobbing after a fight, but I pretended I was asleep. My stomach would hurt. I have never been able to process anger.

They pushed me. I would go to the University and get an education. I wouldn’t be an electrician like him. He refused to teach me a single thing about his work. “I was in the English Building today, and I saw those professors with their feet upon their desks, puffing on pipes and reading books. Boy, that’s the job for you.” When I was first in grade school and used a new word, they would laugh with delight and he’d say, “Boy, howdy!” When I won the radio speaking division of the Illinois High School Speech Contest in 1957, the state finals were in a room on campus in Gregory Hall. My Aunt Martha told me years later that he had hidden in a closet to listen to me.

I always worked on newspapers. Harold Holmes, the father of my best friend Hal, was an editor at The News-Gazette, and took us down to the paper. A linotype operator set my byline in lead, and I used a stamp pad to imprint everything with “By Roger Ebert.” I was electrified. I wrote for the St. Mary’s grade school paper. Nancy Smith and I were co-editors of the Urbana High School Echo. At Illinois, I published “Spectator,” a liberal weekly, my freshman year, and then sold it and went over to The Daily Illini. But that was after my father’s death.

Harold Holmes asked me before my junior year in high school if I wanted to cover the Urbana Tigers for The News-Gazette. This caused a debate at the kitchen table. I was not yet 16. I would have to work until 1 or 2 a.m. two nights a week, and drive myself home. My mother said, “those newspapermen all drink, and they don’t get paid anything.” There was some truth in this. My father said: “If Harold thinks the boy can do the job, we’ll always regret not giving him the chance.” For a story I wrote in the autumn of my senior year, I won the Illinois Associated Press sportswriting contest. In September 1960, when my dad was in the hospital dying of cancer, I took him the framed certificate. It was the most important prize I ever won.

As a younger man, he drank. My mother determined to put an end to this. “She put your father through hell on earth,” Aunt Martha told me. Advised by a family doctor, she added some substance like Antabuse to his coffee. When he had his next beer, it made him deathly ill: “He didn’t get up off that Davenport for two days.” This was before I was born, and I never saw him take a drink. When the old Flatiron Building in downtown Urbana burned, he took me down to witness the flames, and I saw tears in his eyes. It had been the home of the Urbana Elks Club. “Why are you crying, Daddy?” “I had some good times in that building.”

We went for drives. We went to Westville, south of Danville, to eat Coney Island hot dogs made the same way he’d had them on West Palm Beach. We went up to Wings, north of Rantoul, to have Sunday dinner, and they brought a tray with kidney bean salad, cole slaw, celery sticks (stuffed with canned cheese), carrots, green onions, radishes, pickled peppers, candied watermelon rinds and quartered tomatoes. Every single time my father beheld this sight, he said exactly the same thing: “They fill you up before you even get your meal.” Then he would glance at me, to signal that he knew he said it every time. That’s how I gained a lifelong fondness for repeating certain phrases beyond the point of all reason. “For this relief, much thanks,” from Dan Curley, via Hamlet. “Too long a sacrifice can make a stone of the heart,” from John McHugh, via William Butler Yeats. “A wee drop of the dew,” from Bob Zonka. “Irving! Brang ’em on!” from Billy Baxter. “Tip top.” These and other phrases are not tics, they are rituals in the continuity of life.

We drove to Starved Rock State Park. Turkey Run State Park. The Great Smoky Mountains. Rockome Gardens (above), the big rock garden in Amish country down around Arthur, Illinois. These destinations I found interesting, the drives boring. I read books in the back seat. Sometime we’d drive with our neighbors Don and Ruth Wikoff and their son Gary, up to Mickleberry’s Log Cabin on 95th Street in Chicago. This was a long drive in the years before the interstates. Sometimes we’d just drive up to Rantoul to see the Panama Limited go barreling through. “It must have been going 90 miles an hour,” my father would say, glancing at me because he said exactly the same thing every single time, no matter how fast it was going. Then my mother would want to run into the Home Theater to get popcorn and Necco wafers, which we would share when, on our drive home, we parked at Illini Field, north of Urbana, to watch the planes land. My father’s great crime in my eyes was that he didn’t approve of a dog for me. “It will ruin the wall-to-wall carpets.” I have already written about my dog Blackie and the time I was sure they lied to me about what happened to him. They told me while we were parked at Illini Field.

Daddy loved music, and as a member of the University staff he could let us into the balcony at Huff Gymnasium to “keep an eye on the lights,” while we watched the orchestras of Harry James, Count Basie, Les Baxter, Stan Kenton, Les and Larry Elgart play for student dances. On his belt he carried a leather pouch with his smaller tools, and a key ring large enough for a prison warden. He needed to be able to get into his buildings at any time. On nights when a fierce thunderstorm would descend, the phone might ring. The lights on campus were out. I would already be awake, ready to get into his maroon 1950 Plymouth for the drive across the dark campus to the University Power Plant. We would plunge into the darkness, he would adjust something, and tell me to stand by the door. Then he would throw a switch and the campus lights would all spring on. We would drive home through the lighted streets.

The University was smaller then, and so was Champaign-Urbana. We went to a cemetery to feed the swans. To the Atkinson Monument Company to pick out pieces of discarded marble for his rock garden. To every dairy that had an ice cream counter. He scouted out little restaurants. There was a place without even a name up by the Big Four shops, where the train men ate. They served breaded perch. There was the Huddle House on University Avenue, which had a counter with perhaps 15 stools, at the front of an enormous building with no apparent purpose. Every time we went there, he speculated that the Huddle House was a front for Russian spies. He liked the Race Inn on Race Street, where you got all the fried smelts you could eat on Fridays. And Mel Root’s on Main Street. You know how I joke about movies with a cafe where everybody in town comes, and they all know one another? Mel Root’s was that place in Urbana.

I wonder what he was really thinking about his life. He married a beautiful woman, and I believe they loved one another. Whatever had happened in West Palm Beach, stayed in West Palm Beach. He married in his late 30s, held a good-paying job, owned his own home on a corner lot. He debated politics with my Republican uncle Everett Stumm, was militantly pro-union, worried me with his depression when Eisenhower defeated Adlai Stevenson the second time. He never said so, but I got the notion the Republicans were not the party of the working man. He read all the time. In another generation, he would surely have gone to the university and read books with his feet up on the desk, so he wanted me to do that for him. Sometimes I resented him, as when blinded by summer sweat working on the lawn when he repeated, “If the job’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well.” He thought rugs were more important than dogs. Did I know how much I loved him? I do now.

In the spring of 1960 I announced that I didn’t want to go to Illinois, I wanted to go to Harvard, like Jack Kennedy and Thomas Wolfe. This was on a warm day, the screen door open in the living room. “Boy, there’s no money to send you to Harvard,” he said. “But I have my own job,” I said. To my astonishment he began to cry. Then I learned what my mother already knew, that a month earlier he had taken the train to Chicago and consulted a specialist who told him he had lung cancer.

Surgery was at Cole Hospital. I waited in the small rose garden, my mother inside. The surgeon closed up his chest and told us he might live two years at the most. He came home. He worked for a few weeks, then took sick leave. He read. Harry Golden, the North Carolina liberal Jew, had a new book out, and he loved Harry Golden. He never missed Lawrence Welk. I was busy pledging a fraternity, dating, working for The News-Gazette, publishing my science fiction fanzine. I would sit in the living room or the basement and read with him or watch TV. He told me he was doing fine. Lighting up a Winston. I saw my mother’s eyes, but we didn’t speak of the unthinkable. He went back to the hospital, and I brought his Harry Golden book over for him.

That day I saw something I am so grateful to have seen. He sat up on the edge of his bed. “Hold me, Bub,” he said. “It hurts so much.” She took him in her arms. “Oh, Wally,” she said, “I love you so much.”