I want to tell you about a woman named Betty Brandenburg. You’ve not heard of her, but her passing must not go unremarked. I’ve written many times about the Conference on World Affairs at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She made it run. She dealt with the most impossible man in Colorado. She was a young widow who raised two children on her own. I met her the first year I went to Boulder, in 1969, and saw her the last time a few years ago at one of the annual Wednesday night dinners our little group held at the Red Lion Inn.

Are you wondering why I’m telling you this? Is this only something personal with me? Why am I involving you? Maybe it’s because of a piece I wrote not long ago, about when we die the most important thing we leave behind is our memory, and when those who remember us die, then we are truly dead. I remember Betty.

She was short, plump and merry. She almost always wore bright red, and red was the color everywhere in her house. She raised Karl and Kaye and they were happy and successful. She always had two or three big dogs around. In the 1980s she bought a house in the country north of town, so the dogs would have room to roam.

Most of the visitors to CWA live with a local family, their “houser,” and Betty was my houser, first in Boulder in the brick house on Lincoln and then out in the country. She confided in me that when I was doing a lot of drinking in the 1970s and coming home late, some of my housers had worried. That’s why she took me in. Something like that didn’t bother Betty.

Her full time job was as secretary for Howard Higman, a professor of sociology and the founder of the Conference. When I say “full time job,” I mean 24-7. Night after night during a conference, the phone would ring at 2 or 3, and Betty’s voice could he heard through the wall, calming Howard during one of his tantrums. Howard was no doubt a brilliant man, but as I said, an impossible one. He was Falstaffian, he wore a famous coat of many colors, he ranted and roared, and once got into a duel on his own staircase–his oak stick against a visitor’s sword-cane.

Enough about Howard. Betty was the diplomat. She knew everyone and everyone knew her. She worked with the committee to arrange meetings, housing, transport, volunteers to meet guests at the airport. There was a dinner for everyone every night at a different big house in town, and Friday night was “Betty’s dinner.” She, her sister and some local friends did all the food. In their own kitchens, they made Caesar salad, lasagna, garlic bread and butterscotch chip cookies. It was held a huge Victorian mansion up on a hill, the city lights twinkling beneath.

“Take your shower tonight,” she told me on the first Thursday night I stayed with her. “The tub is off limits on Fridays.” They scrubbed it carefully and filled it with romaine, which they washed before throwing in Mandarin oranges, bags of croutons and Betty’s special salad dressing. They transported it to the party in big plastic garbage bags.

Her crew took over the kitchen, which was on the route from the dining room to the bar. There were always a few drunks who set up shop midway. That was okay. It was a pretty free-wheeling conference. Betty used her observation post to stay updated on every scrap of gossip and scandal, every affair, every new outrage by Howard.

To tell you the truth I don’t know if Betty was a college graduate. I realize now she must have been. We had so many talks, so many dinners together, so many midnight de-briefings, but it never came up. She was a specialist in human beings. She had a way of being amused by what she called “Roger’s characters”–buddies like Jay Robert Nash and John McHugh who I got invited to the Conference. One year St. Patrick’s Day fell on our Wednesday and McHugh tucked a $20 bill into the accordion player’s vest pocket and instructed him, “Keep on playin’ Danny Boy until that runs out.”

Nash, the famous writer about crime, was along the night we all drove up to the Gold Hill Inn, a legendary restaurant and saloon high on the mountain above Boulder. The local residents were a fairly rugged crowd, gathered around the fireplace in the front room, their feet up on the guard rail, their hats tipped back, sipping Jack and rolling their own.

Nash, a dapper lookalike for Jimmy Cagney, sauntered over and said, “So, you fellas call yourself cowboys?” In a flash, just as the fellas were slowly mounting to their feet, Betty was in between, pushing Jay away, calling back over her shoulder, “It’s okay, boys. He’s new in town.”

I believe Betty remembered almost every one of the participants who attended CWA over the years. One of them haunted her. “He was some Russian philosopher who Howard invited,” she told me. “He flew into Denver, rented a car, drove up to Boulder, got in car crash, and was killed instantly. None of us ever saw him.”

Betty always seemed young. She must have been older than me. I have no idea. Her health began to fail; she had a stroke. Her children were now grown up and living away, and they moved her into an assisted living facility. Chaz and I would see her on Wednesday nights, when her pals from the CWA, like Rich and Linda Loose, would pick her up and bring her to the dinner in a wheelchair.

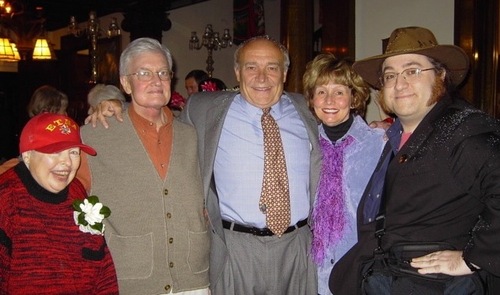

The Red Lion is a big log building maybe 15 minutes above town, specializing in entrees like the Genghis Khan Sword (steak and lobster, as I recall). A group of us, maybe 20, would take over a big upstairs room, sit around a long table, and–well, mostly we told dirty jokes, although Bill Nack would always recite the last page from “The Great Gatsby,” Andy Ihnatko would read from Wodehouse, I would tell my limericks, and Simon Hoggart, the London parliamentary correspondent, would quote obscene parrots. One year both Studs Terkel and Molly Ivins were there, right across from Betty, who was beside herself with joy. Her two greatest liberal heroes. She never talked politics. She took them for granted: “All decent people are liberals,” she once explained, “and then every year Howard invites some conservatives, just to cause trouble.”

My health troubles have kept me away from Boulder in most recent years. I probably saw Betty the last time in 2006, before my first big surgery. On Monday, I received this email from Maura Clare, the CWA secretary:

“Friends of Betty Brandenburg here in Boulder had a shock this weekend. Bob McClendon called over to the assisted living facility where Betty has been living most recently to arrange a visit and was told that Betty died last November. None of us could understand how we could have not heard about this–and were heartsick to learn the news so belatedly.

“We were eventually able to track down Betty’s daughter Kaye. Kaye had her hands full with a move to Florida at the time Betty died. Her brother Karl, who lives in Colorado–though not in Boulder County–made arrangements with a local funeral home. It was Karl’s understanding that the funeral home would post an obituary, but they did not. Kaye and Karl just assumed everyone at the CWA had read about Betty’s death in the paper.”

Kaye and Karl hadn’t been much involved in the Conference, which even as small children they learned to think of as the week their mother became invisible. They did their share of helping out, but most of their mother’s contemporaries, the ones they knew, would have died. It was a new generation. There were no longer as many people who had known Howard Higman. Time passes.

Betty Brandenburg knew everybody, and everybody knew Betty. For more than 40 years she was the tireless little life force in red, who kept things humming. She made plans, soothed feelings, practiced diplomacy, tamed Howard, and made salad in a bathtub. When she died, she had disappeared into old age. But I remember her. So do many other people, far away from Boulder. As much as any single person she was responsible for that remarkable event at which ideas were the only negotiable currency. Leonard Feather, the jazz critic, once called the CWA “The Leisure of the Theory Class.” Betty, who had so little leisure, liked that.

Photo at top of page: At the Red Lion Inn. Betty, Roger, Bill Nack, his wife Carolyne Starek, and Andy Ihnatko. Photo below: Betty with Khan Manther, her grandson.

My original CWA entry, the Leisure of the Theory Class. My last CWA entry, Goodbye to all that.