I was born at the center of the universe, and have had good fortune for all of my days. The center was located at the corner of Washington and Maple streets in Urbana, Illinois, a two-bedroom white stucco house with green canvas awnings, evergreens and geraniums in front and a white picket fence enclosing the back yard. Hollyhocks clustered thickly by the fence. There was a barbeque grill back there made by my father with stone and mortar, a dime embedded in its smokestack to mark the year of its completion.

There was a mountain ash tree in the front yard, and three more down the parking on the side of the house. These remarkable trees had white bark that could be peeled loose, and their branches were weighed down by clusters of red-orange berries. “People are always driving up and asking me about those trees,” my father said. He had planted them himself, and they were the only ones in town–perhaps in the world. They needed watering in the summertime, which he did by placing five-gallon cans under them with small holes drilled in their bottoms. These I carefully filled with the garden hose from the back yard, while making rainbow sprays over the grass around.

My bedroom was the one with the window overlooking Maple Street. It had a two-way fan, posing the fundamental scientific question, is it more helpful on a hot night to blow cooler air in, or warmer air out? I had better get to sleep quickly, because Harry With His Ladder would come around to look in and be sure my eyes were closed. I lived in fear of Harry, and kept my eyes screwed tight until I drifted off to sleep.

Of this room as a very young child I remember only a few things. My mother putting me to sleep in a bed with sides that rose up to prevent me falling out. A nightly ritual of love pats. My small workbench on which I hammered round pegs into round holes. A glass of water which was filled to the rim, but which I could see straight through, so obviously there was room down there for more water. My tears when I was accused of playing with water and spilling it, when I had been following strict logic.

Of this room as a very young child I remember only a few things. My mother putting me to sleep in a bed with sides that rose up to prevent me falling out. A nightly ritual of love pats. My small workbench on which I hammered round pegs into round holes. A glass of water which was filled to the rim, but which I could see straight through, so obviously there was room down there for more water. My tears when I was accused of playing with water and spilling it, when I had been following strict logic.

A little later, I had my own bed with a headboard, and could charge down the hallway and leap onto it like superman. Warnings that I would break the bedboards. My own little radio. I would lie on the floor under my bed, for safety, while listening to “The Lone Ranger.” I thought “Arthur Godfrey and His Friends” were friends about my age. I had a bookcase in which I carefully arranged first childhood books, and then books about Tarzan, Penrod, Buddy, the Hardy Boys and Tom Corbett Space Cadet. Also Huckleberry Finn, the first book I ever read and still the best.

When I was sick it was the best time. I could stay in bed and listen to “Our Gal Sunday,” which was “the story of whether a young girl from a small mining town out in the West can find happiness as the wife of a wealthy and titled English lord.” Before that there was “Penny for Your Thoughts,” where people got a penny just for calling up Larry Stewart and talking to him. Larry Stewart was also “The Voice of the Fighting Illini,” my father informed me. The Illini were the University of Illinois, the world’s greatest university, whose football stadium my father had constructed–by himself, I believe. It was there that he had seen Red Grange, the greatest player of all time. Also in that stadium were seen the world’s first huddle, the world’s first Homecoming, and Chief Illiniwek, the world’s greatest sports symbol (“Don’t ever call him a mascot,” my father said. “Chief Illiniwek stands for something.”)

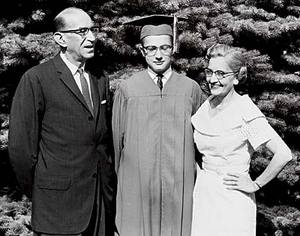

Annabel and Walter and their boy

Annabel and Walter and their boy

The University also had the world’s largest arched roof, over the Armory. The cyclotron, where they worked with atoms. The Power Plant, with its towering smokestacks. On nights when there was a downpour, the phone might ring and my father would say, “Come on, boy, the lights are out.” We would drive in the maroon Plymouth through the darkened streets to the Power Plant, a looming coal-smelling building which my father would enter with a flashlight and do something. “All right, boy,” he would say. “Stand by the door.” He lighted my way with the flashlight. Then all of the lights on the campus would come back on, and we would drive home, me asleep in the car, although I could tell when we hit Race Street because the bricks smoothly rumbled beneath the wheels.

There was also the Illiac, in a whole building filled with vacuum tubes that could count faster than a man. My dad worked in there. “Your father is an electrician for the university,” my mother told me. “It can’t run without him. But I’m afraid every day that he’ll get shocked.” I didn’t know what that meant, but it sounded almost as bad as being “fired,” a word I also didn’t understand, although thank God that had never happened to my father. There was the Natural History Museum, with its stuffed owls and prehistoric bones. Altgeld Hall and its bells, which could be heard all over town in the summer, and which my father had personally installed, I believed.

Click and enlarge to see the shiny new dime

Click and enlarge to see the shiny new dime

The town also contained a cemetery where we would go to watch see the swans float on the pond. And a Cemetery Graveyard, next to the Atkinson Monument Company in a lot overgrown with trees and shrubbery, where pieces of broken gravestones were there to be picked through for the rock garden my father was building. If you got lost in the Cemetery Graveyard, the ghosts might come for you. There was the Boneyard, a creek running through town, where the Indians had buried their dead. An airport where we could see Piper Cubs taking off. A train station north of town, in Rantoul, where we could watch the Panama Limited and the City of New Orleans hurtling through, the world’s fastest trains.

I attended Mrs. Meadrow’s Tot’s Play School during the day. This was because my mother was a Business Woman–in fact, the president of the Urbana Business Woman’s Association. She was a bookkeeper for the Allied Finance Company, up a flight of stairs over the Champaign County Bank and Trust Company. It was run by Mr. Willis. On the first of every year they worked all day to get the books to balance. When they succeeded, Mr. Willis would take us all, including my father and me, to dinner at Mel Root’s two doors down Main Street. In between the bank and Mel Root’s was the Smith Drug Company, where Mr. Willis bought me by first chocolate soda. My parents smoked Lucky Strikes, but Mr. Willis smoked Chesterfields.

Our house had a concrete front porch on which rested four steel chairs you could rock in. On summer nights my mother would make lemonade and we would all sit out there. They would smoke and read the papers, and talk to neighbors walking past. Later you could see fireflies. The sounds of radios and voices, sometimes laughter, would float on the air. On spare days, there were jobs to do. Pulling up dandelions. Picking tomato worms off the tomato plants in our vacant lot. A riskier job, climbing a stepladder to pick bagworms off the tallest evergreens. A more exciting job, in the autumn, dressing in old clothes and crawling up the air pipes from the furnace while dragging the vacuum cleaner hose, to pull the dust out.

In winter I was awakened by the sound of my dad shoveling coal into the stoker. In summer, of the clip-clops of the horses pulling the wagons of the Urbana Pure Milk Company. Sally Hopson’s family owned the milk company. The whistles of passing trains could be heard all through the night. My dad took me to see the Round House of the Big Four Railway. My grandfather came from Germany to work there. He made things from metal. We had a carving knife that he cut from a single block of steel. There was a railroad man’s diner next to the Round House where we would go for meat loaf and string beans, but my first restaurant meal was at the Steak ‘n Shake on Green Street. “A hamburger for the boy,” my father said. “But I don’t like ham.” “You’ll like this ham.”

My dad and his fellow University electricians

My dad and his fellow University electricians

When you entered the house from the front porch, you were in the living room, with our fireplace. My father would place little tablets on the burning logs that would make the flames burst into many colors. Here we sat on Christmas Eve to listen to Bing Crosby and His Family. He had a son named Gary who I thought was just about my age. Off the living room was the dining room, nearly filled by the table. Most of the time the center boards were out, so my mother could let down the ironing board from the wall. Then came the kitchen, where my father made his chili and let it sit in the icebox overnight.

A hallway had doors opening to the living room, the kitchen, the bathroom, and both bedrooms. When Chaz and I revisited the house 20 years ago, a woman named Violet Mary Gaschler, who bought the house from my mom, asked us to come in and look around. I was surprised how short the hallway was. When the phone would ring at night, my mother would hurry into it, grab the receiver, and say, “Is it Mom?” My grandmother had heart trouble. Having a Heart Attack was worse than being shocked or fired. On that same visit with Chaz, I went to the basement, and felt chills down my spine. Hardly anything had even been touched. On my father’s workbench, a can of 3-in-One Oil still waited. The chains on the overhead electric light pulls still ended in toy letters spelling out E-B-E-R-T. She let me take an “E.” The basement’s smell was the same, faintly like green onions, and evoked summer afternoons in a lawn chair downstairs, reading Astounding Science Fiction.

A member of the Urbana High School class of 1960. (Photo by Hal Holmes)

It was from the basement that I operated the Roger Ebert Stamp Company, buying 10-cent ads in little stamp magazines and mailing out “approvals” to a handful of customers. One day two men came to the door and said they might want to buy some stamps. I proudly showed them my wares. My mother hovered nervously on the stairs. The men left quickly, saying they didn’t see anything they needed for their collections. Nevertheless, they seemed to be in a good mood. My dad walked in from work. “What did those men want?” he asked. We told him. “Their car said Department of Internal Revenue,” he said.

On April 22, 2009, the city of Urbana honored me by placing a plaque at my childhood home. At first I demurred. I argued that far greater figures had lived in Urbana, such as the sculptor Lorado Taft, the poet Mark Van Doren, the novelists William Gibson, David Foster Wallace, Larry Woiwode and Dave Eggers, the newspapermen William Nack, James Reston, Robert Novak and George F. Will, the Nobel-winner for the invention of the transistor, John Bardeen, and the Galloping Ghost himself, Red Grange. You see that Urbana truly was the Center of the Universe.

Their dream house as they first saw it

Their dream house as they first saw it

The city fathers promised they planned to dedicate plaques to many worthy sons and daughters of Urbana, and so I agreed. As I stood in front of 410 E. Washington, I reflected that this was the first and only home my parents owned. Here they brought the infant Roger home from Mercy Hospital. Here they raised me, and encouraged me in my dream to be a newspaperman, even if it meant working way past midnight on Fridays and Saturdays. Here my father refused to let me watch him doing any electrical wiring. Here he told me, “Boy, I don’t want you to become an electrician. I was working in the English Building today, and I saw those fellows with their feet up on their desks, smoking their pipes and reading their books. That’s the job for you.”

In the 1970s, an article appeared in The News-Gazette about the restoration of the bells in Altgeld Hall. It said the crew had found a note tacked to a beam up in the tower. It said “We repaired these bells on…” I forget the date. It was signed with three names, one of them Walter H. Ebert.

On that early visit to Urbana, I took Chaz to visit my parents’ graves. Close by, my father’s parents are buried. My grandfather’s name was Joseph Ebert. Joseph is my middle name. My father’s middle name was Harry.

The Fountain of Time, by Lorado Taft, an Urbana boy.

Red Grange. My father was in the stadium for some of these games.

Chief Illiniwek’s Last Dance