If you were on Twitter on October 27, 2015, you probably became aware of an epic Twitter thread unfolding in real time, going viral at the speed of light. The thread was by a woman named A’Ziah King (aka “Zola”) and started with four pictures of Zola and another woman, preening for selfies, with the comment: “Y’all wanna hear a story about why me & this bitch here fell out???????? It’s kind of long but full of suspense.” She wasn’t kidding. Over the course of the next 148 Tweets, Zola recounted a tale of taking a spontaneous road trip to Florida with a woman named Jessica, hoping to get some lucrative stripping gigs. But then Zola found herself roped into a crazy whirl of sex work, pimps, guns, not to mention a dude falling off a balcony. The whole thing was a cliffhanger, with thousands of people waiting for the next “dispatch,” but why the thread really grabbed everybody’s attention was Zola’s voice. “I was like … I REALLY gotta go home y’all. Sorry to kill the mood but I cant take no more of this.” “I leave & go down to the pool. I mean, I am in Florida!” She is a born storyteller.

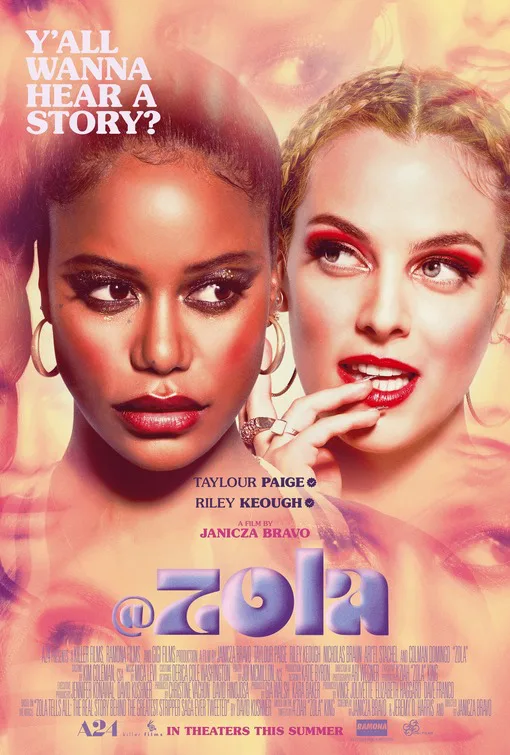

In what is probably a first, that Tweet thread has been adapted into a film, directed by Janicza Bravo, with script co-written by Bravo and Jeremy O. Harris (who wrote the Tony-nominated Slave Play). The original thread unfolded with a propulsive and profane energy, gossipy and funny, even during the most terrifying chapters. There were disturbing undertones, mainly from Zola’s horror of being lured into a situation she hadn’t signed up for, but she zips onto the next thing, a wise-cracking survivor. “Zola” hews closely to the original thread (why fix what isn’t broke?), and often quotes it directly. But what Bravo has done that is most essential is capture the energy of Zola’s voice, and the unique qualities of her perspective. There are many things this tale is, but there are also many things this tale isn’t, and Bravo recognizes the distinction.

When Zola (Taylour Paige) meets Stefani (Riley Keough), while waiting on her at a sports bar (the original was a Hooters), there’s an instant connection. You could say that Stefani “love bombs” Zola, overwhelming her with compliments. Stefani is clearly a mess (later in the film, Zola yells at her: “YOUR BRAIN IS BROKE!”) and her exaggerated accent is put-on and culturally-appropriated in the extreme, but there is something irresistible about her too. When Stefani invites her to come to Florida for a good stripping gig, Zola thinks it might be fun, even though it’s a little early in their friendship to go on a “hoes trip”. However, when Stefani picks Zola up the next morning, Zola is dismayed to see two other people in the car, Stefani’s “roommate” known only as “X” (Colman Domingo) and Stefani’s hapless jealous boyfriend Derrick (Nicholas Braun). When Stefani admits to Zola that X “takes care” of her, Zola knows the score. He’s a pimp, and not only that, he plans to set them both to work the minute they hit Florida. The red flags were everywhere from the jump—watch the look on Paige’s expressive face when Stefani keeps calling her “sis”—but Zola figures she can handle it.

It’s hard to imagine another filmmaker doing what Bravo does with this material. Her style is very free, very open, while remaining specific and crystal-clear. (Seek out her first short film “Eat,” starring Brett Gelman and Katherine Waterston. It has everything: atmosphere, suspense, character development … and it’s only 14 minutes long. All of her short films are like this. Bravo emerged from “Eat” fully-formed as an artist.) Bravo perceives the dark undertones, but she also understands the initial exhilaration. This story needs both. There’s a sequence when they all jam out to Migos’ “Hannah Montana” in the car, shouting the lyrics in unison, filming each other, gyrating in their seats, exhilarated by the sun and sand and blue water zipping by outside, as they enter the freedom of anarchic anything-goes Florida. (This is then undercut by slow shots of what they see outside the windows: first, an enormous white cross free-standing on the road-side, then a Confederate flag at half-mast, billowing in the wind. Welcome to Florida.) Social media plays a key role in the narrative, and not just because the story originated there, but because of how the characters utilize it all along the way. The sound design reflects this reality, with phone-chirp alerts punctuating the action. There are other flourishes, but they’re used sparingly. Nothing clutters up the screen. Periodic freeze-frames give Zola a chance to interject her thoughts to us, her captive audience: “From here on out, watch every move this bitch make.”

Bravo’s sensitivity to atmosphere is everywhere apparent. A huge liquor store transforms into a surreal dreamspace, a posh hotel lobby echoes with an emptiness almost ominous, Zola, wearing a canary-yellow bikini, stands on a balcony, surrounded by the blue of night, a solitary lonely figure snatching some solitude from the craziness. There are repeat shots of dark highways, blurry stoplights, freeways and backroads, as the women are driven around Florida for their assignments, and these “road” sequences are lonely, painterly, beautiful. Zola is an experienced woman but there is an aspect to all of this reminiscent of Alice going through the looking glass. Mirrors dominate, and this is not just a facile symbolic nod, but a serious thematic choice. In one mirror sequence, the two women get ready together for their night out, putting on makeup side by side, as the mirrors proliferate their reflections, the two of them lost in a trance of self-absorption. (There’s a similar sequence in “Scandal,” the 1989 film about the Profumo affair, when Joanne Whalley-Kilmer and Bridget Fonda get themselves ready for a party, in a daze of autoeroticism.) There’s another sequence where Zola’s image is multiplied across the screen five times over, as she murmurs, “Who you gonna be tonight, Zola?” When Stefani interjects her own side of the story (as actually happened, the real-life counterpart taking to Reddit to defend herself), there’s an entire tonal shift, as well as a color-scheme shift: Stefani’s world is all pink-cupcake-hues, her braids now replaced by a “Vertigo“-style updo, all classy and victimized, pulling white-woman rank on Zola, whom she claims got her into this mess.

Riley Keough is way, way out on a limb with her performance of this grotesque woman, a liar, a user, not in any way “likable” but with enough infectious charm it makes sense why Zola was initially seduced (because it was a seduction). Paige is the center of the film, though, and she holds it with a powerful grounded sense of her own worth and an insistence on remaining sane, despite the lunacy of everyone around her. Paige speaks worlds with her eyes, and it’s a joy to watch her change tack on a dime (see her quicksilver no-nonsense attitude when she realizes Stefani is being taken advantage of by X). Both Domingo and Braun give funny broad performances, and X’s intermittent African accent, which comes out only when he’s angry, is an ongoing joke.

Perhaps the strongest aspect of “Zola” is Bravo’s refusal to shy away from one of the most challenging qualities to portray in film (or anywhere else, for that matter, especially on social media): ambivalence. What is the film’s attitude towards the events onscreen? What is the film’s attitude towards sex work? Towards X? Towards Stefani? There are times when it seems cut-and dried. There are other times when it’s not so clear. The scenes of the two women stripping are luscious and playful, but then there’s the moment when a client tips Zola, murmuring that she looks like Whoopi Goldberg. The pleasure is real but so is the disgust. The sex work scenes have distressing elements, but they are also introduced by shots of a diverse array of penises. Heart emojis flower over the biggest specimen. It’s not that it’s complicated so much that it’s ambivalent. Ambivalence is such a common experience to most human beings, and yet it’s treated as a huge no-no in contemporary storytelling. People like their villains clear-cut and they like bad behavior to be signaled as “bad” with huge neon arrows. Bravo isn’t interested in that kind of simplified binary, and it’s the stronger film for it.

The only disappointment in all this dazzling creativity is that the ending feels almost cut off in mid-sentence. But that’s a quibble. This is the kind of film that tells its story well while simultaneously showing the joy of the creative act, in Bravo’s filmmaking, yes, but also in Zola’s decision to take to Twitter and tell her story in the first place. A voice like hers doesn’t come along every day.

In theaters now.