“Yourself and Yours,” the latest black comedy by Korean writer/director Sangsoo Hong to receive an American theatrical release (it was filmed in 2016, and released later that year, as well as in 2017), is an exhausting, and mostly frustrating display of emotional scab-picking. Which is disappointing, though not quite unexpected, given that “Yourself and Yours” is a film written and directed by Hong, a prolific and vigorously self-lacerating writer/director whose self-mythologizing films somehow became even more self-absorbed after 2016, when Hong unsuccessfully filed for a divorce with his wife. This is the sort of unproductively detailed confessional fantasy that only depreciates in hindsight; the more we know about its subject, namely Hong, and his well-publicized affair with actress Minhee Kim, whose absence in “Yourself and Yours” is glaring.

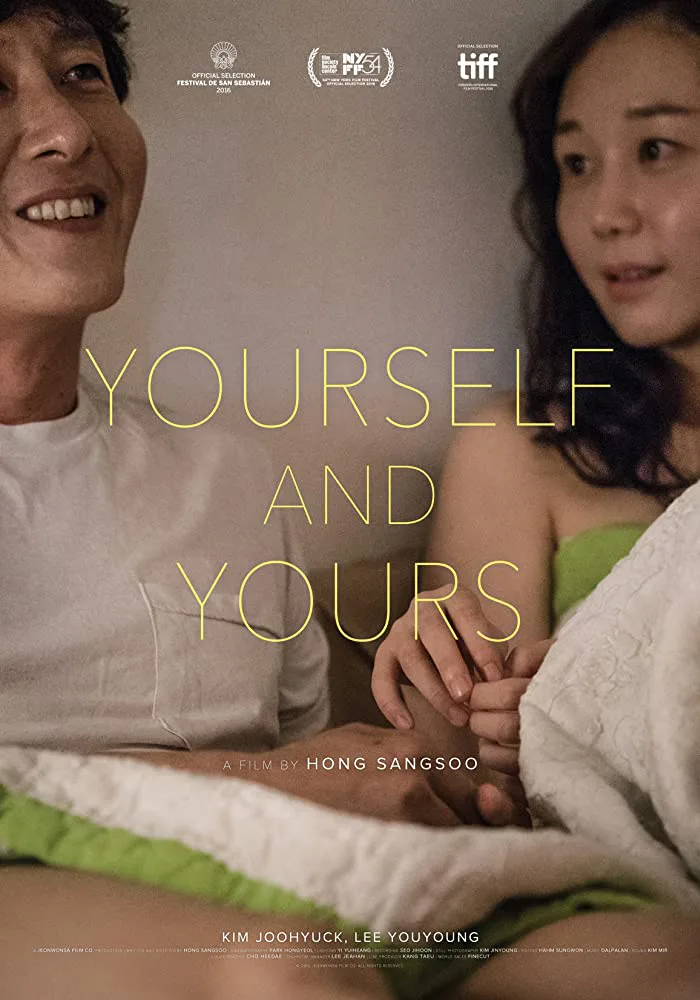

“Yourself and Yours” now feels like an unsteady bridge between Hong’s pre- and post-2016 work since it’s a characteristically disjointed series of vignettes about a drunken artist (Joohyuck Kim) who’s obsessively worried about his partner (Yooyoung Lee) and what may or may not be her ulterior motives. Watching “Yourself and Yours” in 2020, after five of Hong’s six succeeding films have been released in America, is a bit like revisiting the scene of a crime years after it’s been thoroughly picked over: there’s some evocative stuff here, but even Hong’s worst recent films are more gratifying than this.

In “Yourself and Yours,” frustrated painter Youngsoo (Kim) fixates on his withdrawn girlfriend Minjung (Lee) and her alcoholism. Kind of; sort of. Youngsoo doesn’t actually know if Minjung is drinking heavily behind his back, though a couple of his friends have said as much to him anyway. Some of them, including Jaeyoung Park (Haehyo Kwon), try to confront Minjung, but she always eludes her accusers, possibly because the woman that Youngsoo and his friends confront says that she’s Minjung’s twin sister. I mean, who knows, maybe Minjung really does have a twin sister? That’s just the first of several fruitless questions and pronouncements that Youngsoo hashes out over drinks with his gossipy buddies, and then while stalking Minjung outside her apartment, followed by some more drinking at nearby cafes, and then some more daydreaming about what Minjung’s sister (or maybe it’s Minjung?) does when she’s not with him.

Hong lays into Youngsoo’s neuroses with the same wry sense of humor and barbed romanticism that has made him a critical darling. But several scenes in “Yourself and Yours” only seem to exist to show us the various fruitless convolutions of Youngsoo’s paranoiac fantasies, all of which involve Minjung (or a Minjung-like woman) meeting and rejecting her insistent, but superficially shy would-be suitors’ attempts at “[understanding] her completely.” So some scenes back up Youngsoo’s theory that “It’s all fake! All shitting and eating! True love! Only true love is worth anything. The rest is all formality, all crap!” Others scenes confirm Hong’s fascination with his characters’ stream-of-conscious emotional process: “Everything in life is necessary! Nothing is useless.” But while several of Hong’s supporting characters’ points-of-view are considered, most of them are obviously extensions of Hong’s bruised ego, like the young barflies who speculate that Minjung isn’t “pitiful” since she “sees a new man every night,” while another says “It’s Youngsoo who’s pitiful. Our great Youngsoo, reduced to this.” August Strindberg (or maybe Albert Brooks), this guy ain’t.

Youngsoo and Jaeyoung’s dismal late-night tail-chasing sessions are only funny if you really like the one joke that Hong vigorously runs into the ground: these guys can’t escape themselves, so every potentially romantic encounter becomes a new stage for their overwhelming anxieties. Even the funniest expressions of that theme—a park-side meeting where Minjung conclusively dismisses Jaeyoung by saying: “I don’t feel anything for you. Can’t be helped. Anyway, don’t call me anymore.”—are easy to shrug off. Likewise, Hong’s subtly disorienting transition between sketch-like scenes is only sometimes effectively disorienting: Hong’s signature use of long takes and his attendant fascination with pregnant pauses (and his actors’ awkward body language) only adds unnecessary extra steps for moviegoers who have already gotten his joke, and are now waiting for him to go somewhere with it.

Youngsoo’s stasis may be a theoretically rewarding punchline to Hong’s acidic black comedy, but there’s only so much to be gained from watching ugly, unaware characters drowning in their sorrows while lazily grasping for each other. First he says, “I really love you. Nothing else matters.” Then she says, “Was it hard for you” and seems to mean it, but only because she’s obviously a projection of her creator’s self-regard. “Don’t cry,” he says: “I understand.” Your mileage may vary when it comes to this tedious sort of masochistic Cassavetes role-play, but that doesn’t make Hong’s latest American release any more illuminating, or less punishing.

Available on Virtual Theatrical release today, 6/5.