On November 18th, 1953, a humble government biochemist named Frank Olson fell from the 13th floor of the Hotel Statler in New York City. Or maybe ‘fell’ isn’t the right word. Maybe he ‘jumped’? But that doesn’t sound right either, as it’s more of a plunge than a jump. Or maybe he was ‘pushed’? For the next six decades, his son Eric Olson would become obsessed with exactly what happened in that room on that strange night. The story gained national attention in 1975 when the Rockefeller Commission Report revealed that Olson was a part of a program known as MKUltra, which dosed government agents with LSD to see if the drug would result in state secrets being revealed. Olson had been drugged without his knowledge and something led to him going out the window in the middle of the night. It was an experiment gone very wrong. President Ford himself apologized to the Olsons, who also got a large settlement, and the story was over. Well …

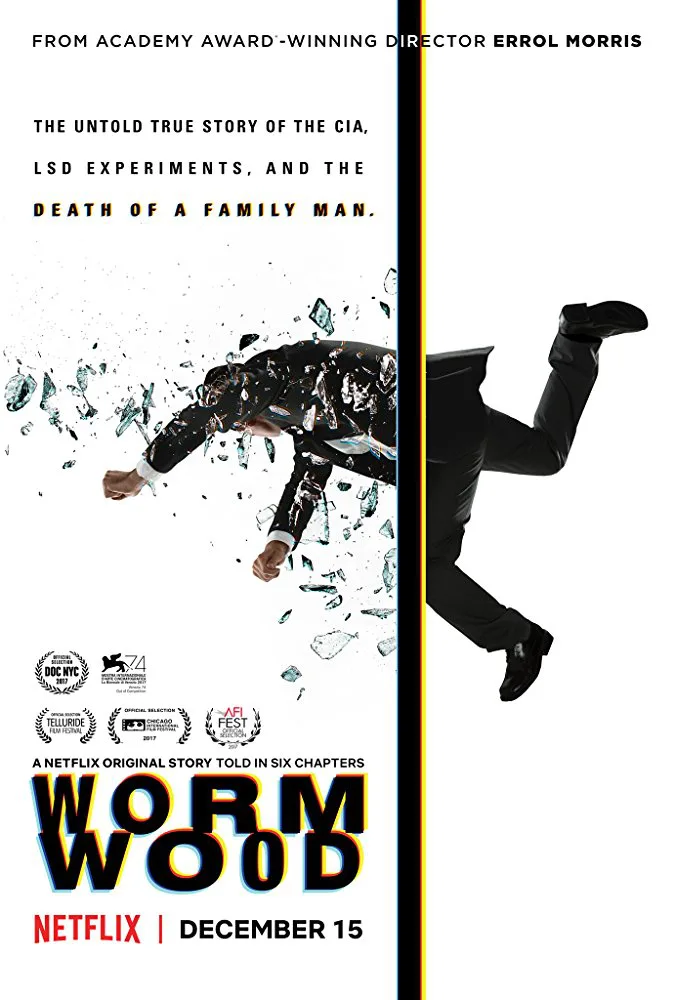

Enter Errol Morris, one of the best documentary filmmakers of all time, and his daring, ambitious “Wormwood,” a 241-minute venture playing in select theaters (with an intermission) or in a six-episode version (which is the same just with credits and episode cuts) on Netflix as of today. Morris has referred to “Wormwood” as his “everything bagel” in that it’s got elements of his entire career folded into this one epic, sprawling story of government-sponsored crime. There is, of course, the true crime expose aspect that reminds one of “The Thin Blue Line.” There is the history of covert ops and government secrets that is reminiscent of “The Fog of War” and “Standard Operating Procedure.” And then there’s Eric Olson, a perfect Morris interview subject with his high degree of obsessiveness, something the filmmaker has returned to over and over again in films like “Gates of Heaven” and “Fast, Cheap, & Out of Control.” But “Wormwood” is not merely a Greatest Hits; it’s a fascinating piece of filmmaking that challenges the form in new ways as it recalls themes its director has been interested in his entire career.

Rather than deliver a standard interview doc, Morris intercuts his conversations with Olson and other key players in this story with filmed recreations of Olson’s last days on Earth, featuring a cast that includes Molly Parker, Tim Blake Nelson, Jimmi Simpson and Peter Sarsgaard as the doomed G-man. Morris allows the recreations to unfold slowly and deliberately, at a pace he would never be allowed in a standard-length documentary, and it adds to the mystery of the entire piece in the way it enhances the mood. There are a lot of furtive looks and worried brows, and while they do start to feel repetitive around the start of the third hour, where “Wormwood” lost me ever so slightly before getting me back near the end, there’s a very definite purpose here. Eric Olson has spent over a half-century thinking about what happened over the last week of his life—it makes sense that Morris wouldn’t want to rush through that. It’s a length and style that adds to the gravity of it all.

The intercutting of the recreations with the interview footage and other formal choices by Morris—for example, he’ll often place archival footage in one half of the screen and then insert that footage on an old-fashioned TV in what looks like a hotel room on the other half, placing history and recreation of history next to each other—make “Wormwood” feel like a maze for the viewer as well as Olson. We’re trapped in this story too, however never in a way that’s disorienting or frustrating. It’s a finely-controlled sense of confusion and even chaos. It’s like a labyrinth in which we can see the path in front of us but our sense of direction and the overall geography is constantly changing. And we’re going around in circles. We’re still following Olson and Morris through that maze, but we keep circling back to that room, that night, what happened—and we realize we’re no closer to an exit.

The most daring element of “Wormwood” really comes in the final installment in which Morris gets to the key question rarely asked in true crime exposes—then what? If Eric Olson proves that his father was a part of some grand government conspiracy or possibly even murdered by them, what happens then? Where does that knowledge take us? It’s almost as if Morris is suggesting that Olson, and really us as a nation, will always be in that maze, where truth and justice are around a corner we just can’t seem to find.