Fifty years ago this week, on May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that “separate but equal” could no longer be the rule of the land. Its decision in the case of Brown vs. the Board of Education ended segregated schools and opened the door for a wide range of reforms guaranteeing equal rights not only to African-Americans but also, in the years to come, to women, the handicapped, and (more slowly) homosexuals.

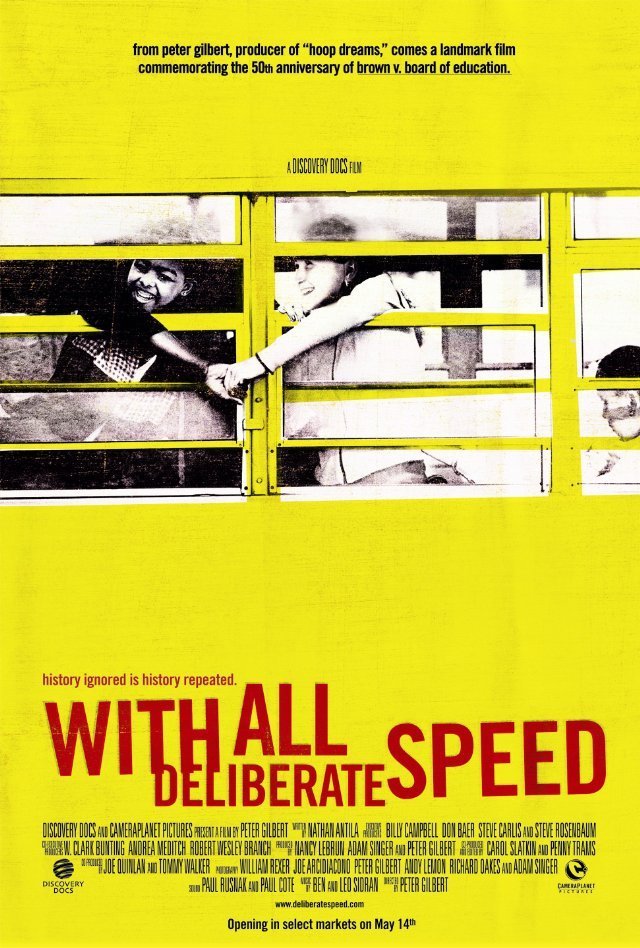

The decision was a heroic milestone in American history, but it was marred, this new documentary says, by four fateful words: “With all deliberate speed.”

Those words were a loophole which allowed some Southern communities to delay equal rights for years and even decades; the last county to integrate finally did so only in 1970. And there was the notorious case of Prince Edward County, Va., which closed its schools for five years rather than integrate them. Most people alive today were born after Brown and take its reforms for granted. But “With All Deliberate Speed,” the documentary by “Hoop Dreams” producer Peter Gilbert, doesn’t end on May 17, 1954. It continues on to the present day, noting that many of America’s grade and secondary schools are as segregated now as they were 50 years ago.

The most valuable task of the film is to re-create the historic legal struggles that led to Brown, and to remember heroes who have been almost forgotten by history. Chief among them is Charles Houston, who was the first African-American on the editorial board of the Harvard Law Review. As dean of the Howard University law school, he was the mentor for a generation of black legal scholars and activists who would transform their society. Although he died in 1950, before Brown became law, it was his protege Thurgood Marshall who argued the case before the Supreme Court, and later became the first African-American on the court.

It was Houston, the film says, who shaped the legal groundwork for Brown, arguing in the 1930s and 1940s that “separate but equal” could not, by its very nature, be equal. He helped persuade the NAACP to mount legal challenges against segregation, and Marshall led the organization’s legal efforts from 1940 onward. The film talks with the descendants of Houston and Marshall, and with many of the law clerks, now elderly, who as young men, served the justices who brought down the landmark decision.

It also recalls the crucial role of Chief Justice Earl Warren in guiding his fellow justices toward what he felt had to be a unanimous decision. The previous chief justice, Fred Vincent, had little enthusiasm for such a controversial ruling. When he died, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed the former California governor Warren as chief justice; justice Felix Frankfurter famously told his clerk that the death of Vincent “showed there is a God.” So hated was Brown in some right-wing circles that an “Impeach Earl Warren” campaign continued throughout his term.

The film also tracks down some of the children involved in the first crucial cases, such as Barbara Johns of Prince Edward County. And it brings belated recognition to another hero of the time, the Rev. Joe DeLaine of Summerton County, S.C., who led the legal struggle against a system that required many black students to walk seven miles each way to school. His church was burned, his home was fired on, he was forced to flee the South, and only in October 2000, 26 years after his death, were charges against him cleared by the state.

Gilbert of course has no audio or video footage of the arguments before the Supreme Court, but he uses an interesting technique: He employs actors to read from the words of Thurgood Marshall and his chief opponent, the patrician John W. Davis. And he does a good job of recapturing the 1954 impact of the decision — with which, he notes, Eisenhower at first privately disagreed, although Ike later came around, and sent federal troops to enforce integration in the late 1950s.

What is the legacy of Brown? It’s here that Gilbert’s film is most challenging. It observes that while many communities have truly integrated schools, patterns of residential segregation in many areas have resulted in schools where the students are almost entirely of one race. He talks with blacks and whites who are in a tiny minority in their schools and listens to discussions of race by today’s high school students.

And in reunions held today, he gathers students, now grown, who were at the center of the original case, and hears their memories of what it was like then and what it is like now. America moves imperfectly toward the goal of equality, but because of Brown vs. Board of Education, it moves.