It strikes a note of optimism, I suppose, that “Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself” is not titled “Wilbur Kills Himself.” Wilbur certainly tries desperately enough, with pills, gas, hanging, and teetering on the edge of a great fall. But he never quite succeeds. He is saved more than once by his brother Harbour, and on another occasion by Alice, who interrupts his hanging attempt. By this point we begin to suspect that “Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself” is not about suicide at all, that Wilbur is destined for better things, and that despite its title, this is a warm human comedy.

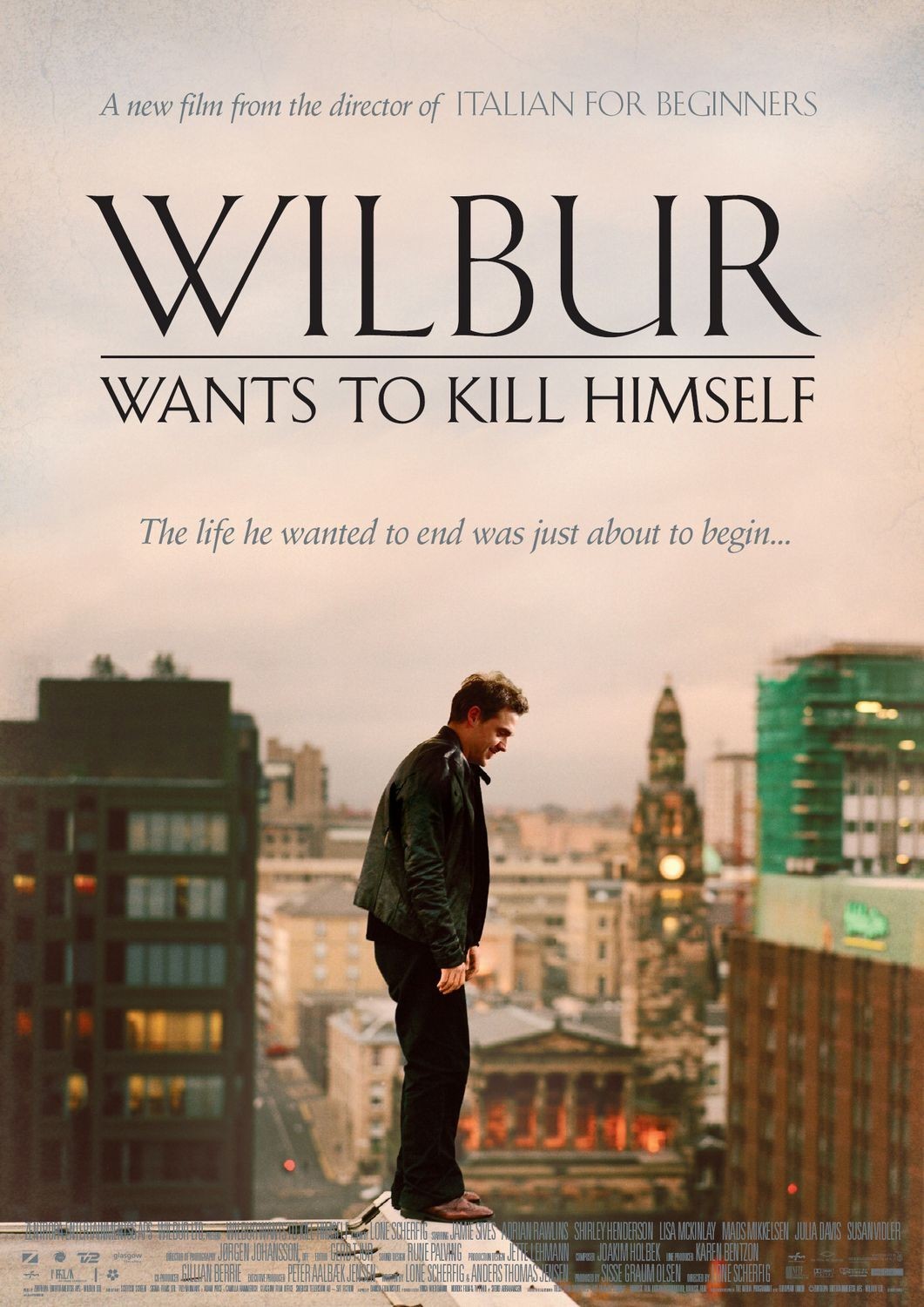

The movies takes place in Glasgow, that chill city where many views are dominated by the Necropolis, the Gothic cemetery on a hillside overlooking the town. Such a view must be a daily inspiration for Wilbur (Jamie Sives). He is from time to time a patient at a local psychiatric clinic, where the therapists seem to have limited their studies to viewings of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.” His hopes depend on his brother, Harbour, who loves him, tries to save him from himself, and brings him home to live with him. Harbour (Adrian Rawlins) runs the used bookstore left him by his father. It is a shabby but inviting place, its windows following the curve of the road, its stock in a jumble. There seems to be only one customer, a man who visits almost daily, demanding Kipling and is invariably told that there must be some Kipling around here somewhere, but Harbour can’t put his hands on it.

Another frequent visitor wants to sell, not buy. This is Alice, played by Shirley Henderson, that luminous actress from “Trainspotting,” “Bridget Jones's Diary,” “Topsy-Turvy” and half a dozen others; do not be put off that she played Moaning Myrtle in “Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets.” She brings in books that were left behind by patients at the hospital where she works, but the books are really an excuse for seeing Harbour, who she feels a strange affinity for; perhaps they met in earlier lives, since Rawlins played Harry Potter’s father.

In no time at all Alice and Harbour have fallen in love. Alice and her daughter Mary (Lisa McKinlay) bring order to the store, so that Kipling can easily be found, and then Alice and Harbour are married. That leads to rather cramped living conditions in the small flat above the store, where Wilbur is also established.

This doesn’t add up to a lot of incident, but it occupies more than half the movie, because the director and co-writer, Lone Scherfig, loves human nature and would rather enjoy it than hurry it along with a plot. The pleasure of the movie is in spending time in the company of her characters, who are quirky and odd and very definite about themselves. There is also a certain amount of escapism involved, at least for somebody like me, who would rather run a used book store than do just about anything else except spend all my time in them.

Now then. The real heart of the movie involves events I do not want to even hint about. That’s because they creep up on the characters so naturally, so gradually, that we should be as surprised as they are by how it all turns out. Let me say that the bleak comedy of Wilbur’s early suicide attempts is replaced by the deepening of all of the characters, who are revealed as warm and kind and rather noble. The movie’s ending is almost unreasonably happy, despite being technically sad, and the affection we feel for these characters is remarkable.

The filmmaker, Lone Scherfig, is a Danish woman whose first film, “Italian For Beginners,” was a Dogma comedy. That she was able to make a Dogma comedy tells you a great deal about her. Here she does away with the Dogma rules and makes a movie in the tradition of the Ealing comedies produced in England in the 1950s and early 1960s: Modest slices of life about people who are very peculiar and yet lovable, and who do things we approve of in ways that appall us. The title may put you off, but don’t let it. Here is a movie that appeals to the heart while not insulting the mind or forgetting how delightful its characters are.