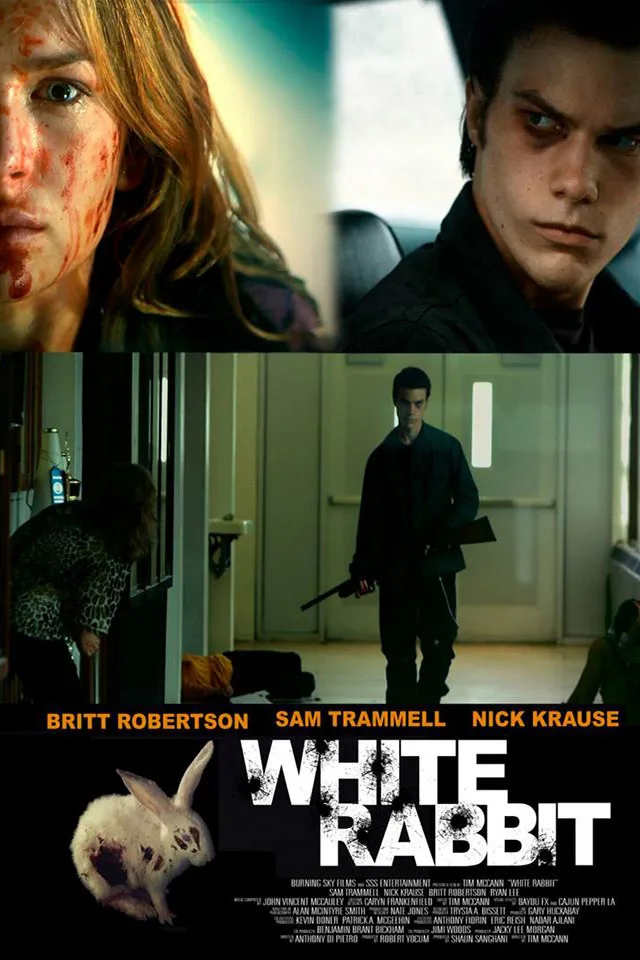

The current box-office sensation “American Sniper” opens with a brief scene showing its main character, rifle at the ready, preparing to gun someone down before flashing back to a childhood memory of going hunting in the woods with his father. Coincidentally, the new psychological drama “White Rabbit” starts off in much the same way, but quickly goes down a much darker path before coming to its grimly inevitable conclusion. The result is one of the bleaker films that you will see anytime soon and while it may not be entirely successful as a whole, it contains enough moments of real power to make you wish that it worked better than it actually does.

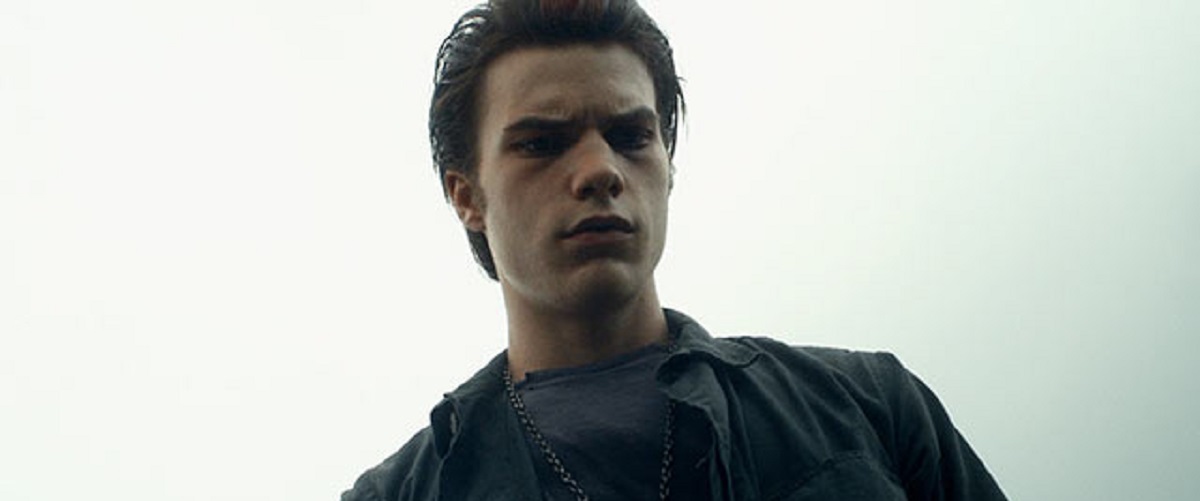

The film tells the sad and grim story of Harlon (Nick Krause), an emotionally traumatized young man growing up in a small town who finds himself the target of relentless bullying from classmates and family members alike. As a child, he suffers endless emotional abuse from his drunken, drugged-out father (Sam Trammell), and equally relentless teasing from his siblings, while his mother cannot muster the strength to do much of anything about it. In a misguided effort to man Harlon up, his dad takes him and his brother hunting one day and forces Harlon to kill the titular lagomorph with the shotgun he was given as a birthday present. This only adds to Harlon’s inner turmoil and leads to him being haunted by visions of the wounded rabbit as well.

Years pass and when we see Harlon again a high school junior, things have clearly gotten worse over time. His dad is still a brute, he is still the target of bullies and the clear signs of psychosis that he is demonstrating are ignored by anyone in a position to help him—instead of recognizing that he has a problem, his school principal coldly informs him that his tanking grades mean that he will be repeating the 11th grade, adding to his humiliations. He has exactly one friend, Steven (Ryan Lee), a younger kid who cries all the time and is another bully target as well, and they pass the time in an abandoned factory shooting things with Harlon’s rifle. One day, they even rescue a dog from a garbage bin and take it home with them but without going into detail, that does not go well.

Things begin to change for the better at last with the arrival of Julie (Britt Robertson), the new girl in town with issues of her own regarding substance abuse. Despite her troubles, she and Harlon strike up some sparks and in a perfect world, they would be able to come together and overcome their respective problems. This is not a perfect world, however, and after a sort-of date goes horribly wrong, Julie disappears for the rest of the summer. When she finally does return as school begins in the fall, she has undergone a number of significant changes that are good for her but which prove to be devastating to Harlon. Finally, Harlon is attacked by another bully and for once fights back in a violent manner, a long-overdue outburst that finally pushes him over the edge with tragic results.

Even without that aforementioned opening sequence, the conclusion of “White Rabbit” would strike most viewers as inevitable—it is a scenario that we have seen far too often in the news in the last few years. The film is less interested in that than in illustrating in painful detail the things that can drive a person to such an extreme and horrifying act. The screenplay by Anthony Di Pietro strives to humanize what most would consider to be inhuman by showing Harlon as a deeply troubled young man who should have gotten help a long time ago (he also has delusions that the characters in the violent comic books he reads are talking to him) but was failed by the very support systems he should have been able to count on—family and school. Throw in the thoughtless cruelties of teenage life and the heartbreak of first love gone bad and he is clearly a powder keg ready to go off, especially with the easy access to firearms that he has as well.

It is an interesting approach for a film but the results are somewhat mixed. On the one hand, the performances by Krause (who you may recall as Shailene Woodley’s goofy stoner boyfriend in “The Descendants“) and Robertson are strong and convincing and Sam Trammell does some interesting things as the father as well, especially in the moments when he lets down his harsh facade and shows traces of vulnerability. On the other hand, there are flaws to the screenplay that director Tim McCann is unable to overcome—the stuff involving the visions of the bunny are too overtly symbolic for their own good while also inviting inevitable comparisons to “Donnie Darko,” another film about a troubled teen haunted by a grim-looking rabbit. I also have a big problem with the very ending of the film and the way that it awkwardly tries to insert a note of ambiguity to the proceedings that only serves to undercut everything that we have seen up until then.

The real elephant in the room, so to speak, regarding “White Rabbit” is that there has already been one brilliant film examining the various ways in which outcast teenagers can be pushed into doing the unthinkable and that is Gus Van Sant’s stunning “Elephant.” This is not to say that another film cannot be made regarding the same topic but if one is to be made, it either has to be better or it has to find some kind of new angle from which to approach the material. “White Rabbit” doesn’t quite manage to do this, and while it has some good performances and noble intentions, it doesn’t really bring anything new to the conversation and ultimately fails to give viewers any compelling reason to wade through all the bleakness and misery that it has to offer.