In 2015, Robert Zemeckis directed “The Walk,” a fictionalized version of the story of Phillipe Petit, the acrobat who in 1974 did a high-wire crossing of the chasm between New York’s Twin Towers. A lot of people thought there wasn’t much point to this (aside from providing actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt, who played Petit, the chance to wield a truly outrageous French accent), given that an excellent documentary about Petit and his feat, “Man on Wire,” had opened to great acclaim and unusual-for-a-documentary box office back in 2008.

But as much as documentaries are more prominent in the mainstream discussion of movies than they’ve ever been, they still don’t have the potential reach of Hollywood product (although “The Walk” proved an underperformer in that respect). And Petit’s story had the raw material to allow Zemeckis to productively play with the special-effects toolboxes he’s been assembling since relatively early in his directorial career (see “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” of course, and “Death Becomes Her,” not to mention “Beowulf” and “ A Christmas Carol;” even his more ostensibly realistic pictures like “What Lies Beneath” and “Flight” were effects-driven in ways that weren’t always immediately evident).

So, too, in its way, does the real-life story of Mark Hogancamp, a resident of the Catskills who once made his living designing and building showrooms for trade shows. In 2000, while drinking in a bar, he mentioned in conversation to a group of men that he enjoyed wearing women’s shoes. The men, five in number, responded to his candor by beating him nearly to death. After waking from a coma, he had no memory of his prior life or the beating, and had to relearn how to walk. Once his Medicare benefits ran out, he repaired to a trailer home and began building a miniature city, peopling it with dolls in period costumes, and photographing the adventures of the dolls. They take place in World War II Belgium, and center around one male U.S. Army Captain, and the attractive women with whom he fights Nazis, who tend in this world to attack in groups of five.

Hogancamp’s photographs were discovered by the “art world” and exhibited therein, and Hogancamp and his work were the subjects of an excellent 2010 documentary “Marwencol.”

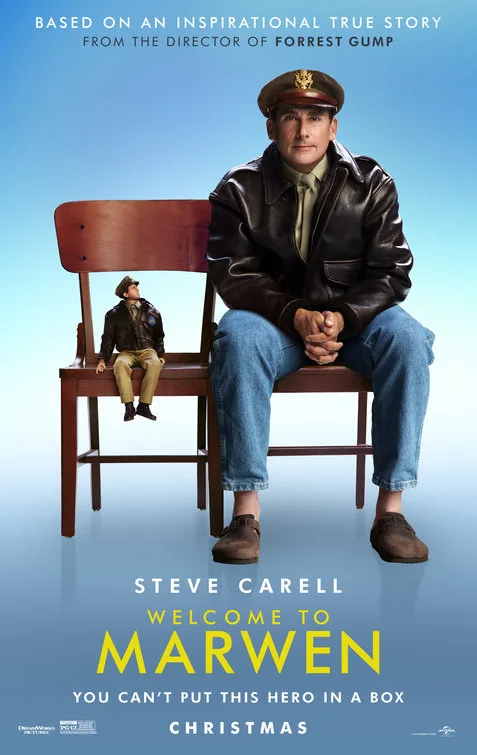

One can see how this story might be catnip to Zemeckis, who has cast a group of first rate human actresses to play not only the dolls, which in Hogancamp’s imagination function like real people, but the women of his world who inspired them. In “Welcome to Marwen,” Steve Carell plays Hogancamp, and Leslie Mann, Janelle Monae, Merritt Weaver, Eiza González, Stefanie von Pfetten, Leslie Zemeckis and Diane Kruger play “the women of Marwen,” all of whom have a corporeal existence outside of Mark’s fantastic world. Except for Kruger’s Deja, a “Belgian witch” whose symbological function in the complicated-in-description but-not-too-tough-a-slog-on-screen narrative will be easily detected by anyone with an ability to match colors.

The fictional narrative was concocted by Zemeckis and Caroline Thompson, who many years ago penned the ultimate” different kind of guy” scenario in “Edward Scissorhands.” And it’s here that my problems with “Welcome To Marwen” began. Having seen “Marwencol” and made myself further conversant with the real-life Hogancamp’s story, I found the fripperies and filigrees of romantic comedy and redemption tale added here to be a cheapening and coarsening of Hogancamp’s real life.

In the documentary, the real life Hogancamp tells how prior to his beating, he was a hardcore blackout alcoholic. When he awoke from his coma, not only his memory was gone but so too was the compulsion to drink. In the documentary this fact registers as something galvanic: to have your brain so thoroughly rearranged as to somehow cure a disease of the mind and spirit is strangely terrifying to contemplate. In the film, the fact is merely shrugged off, the better to make room for Carell’s character to get a creepy fixation on new neighbor Nicol (Mann) while ignoring another real-life Woman of Marwen who has deep feelings for him. And for him to dodge the sentencing hearing of the goons who beat him up, because trauma flashbacks and whatnot. The posters for this movie remind us that Zemeckis also directed “Forrest Gump,” and this movie explicitly Gumpifies Hogancamp, who I hope received a large bag of cash in exchange for allowing the indignity.

I’m a great believer in artistic license; if a “based on a true story” film fiddles with the facts and delivers the goods, I’m not too bothered. People talk about “punching up” versus “punching down” and I suppose “distorting up” and “distorting down” are things also. While Hogancamp has achieved some measure of what one can call “career success” with his artwork, I still see him as an underdog and I left “Welcome to Marwen” feeling that Hogancamp had been cut off from agency from his own story, reduced to a cow-eyed dunderhead Candide only more voyeuristic. Hogancamp’s portrayal by Carell as a quintessential Carell milquetoast is a choice I blame less on the actor than on Zemeckis and maybe the whole damn Hollywood system.

As shown in the documentary, Hogancamp is a (necessarily, given his brain injuries) shambling, gruff figure, constantly puffing on a cigarette. In “Welcome to Marwen,” the filmmakers let the fictional Hogancamp have his coffin nails too, but you never see Carell inhale. That’s emblematic of the entirety of this sentimental movie.

As for those special effects, they are vivid, colorful, convincing. They aren’t quite so good that you don’t notice the WWII fantasy scenarios enacted therein are clichéd constructions reenacted in high heels.