I’d love to see a true satire written by the incredibly smart David Michod. “War Machine,” now on Netflix, isn’t really a satire. I’d love to see a white-knuckle war movie shot by ace craftsman Dariusz Wolski. Believe it or not, “War Machine” isn’t really a war movie. I’d love to see a drama about a man essentially defeated by the system that he helped create. That thread may be in there, but “War Machine” isn’t really a drama either. It is all of these things, and none of them at the same time. It has moments of stand-out greatness, but it’s a scene here and there, a choice by an actor, a great line of dialogue, etc. And it becomes even more frustrating as the scenes that work almost defiantly refuse to work together, like the suits and the soldiers in Michod’s script who never see eye to eye. Critics have a habit of calling movies tonally inconsistent, but this should now be the textbook example, a film that veers wildly from war movie to character drama to satire to history piece to a blended gray of nothing.

Based on journalist Michael Hastings’ The Operators: The Wild & Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan, “War Machine” tells the story of the days of the war in Afghanistan after Barack Obama’s election, when the world was basically just waiting for the conflict to end but people on the ground still had a war to fight. Michod’s script works to convey the complete confusion that must have dominated days in which Obama was sending troops over to Afghanistan and telling the country at the same time that the war would be over soon. What kind of message could that possibly send to soldiers, especially the ones just being sent? And how could the people in charge of planning to win such a war possibly do so when it seemed like everyone involved just wanted them to leave?

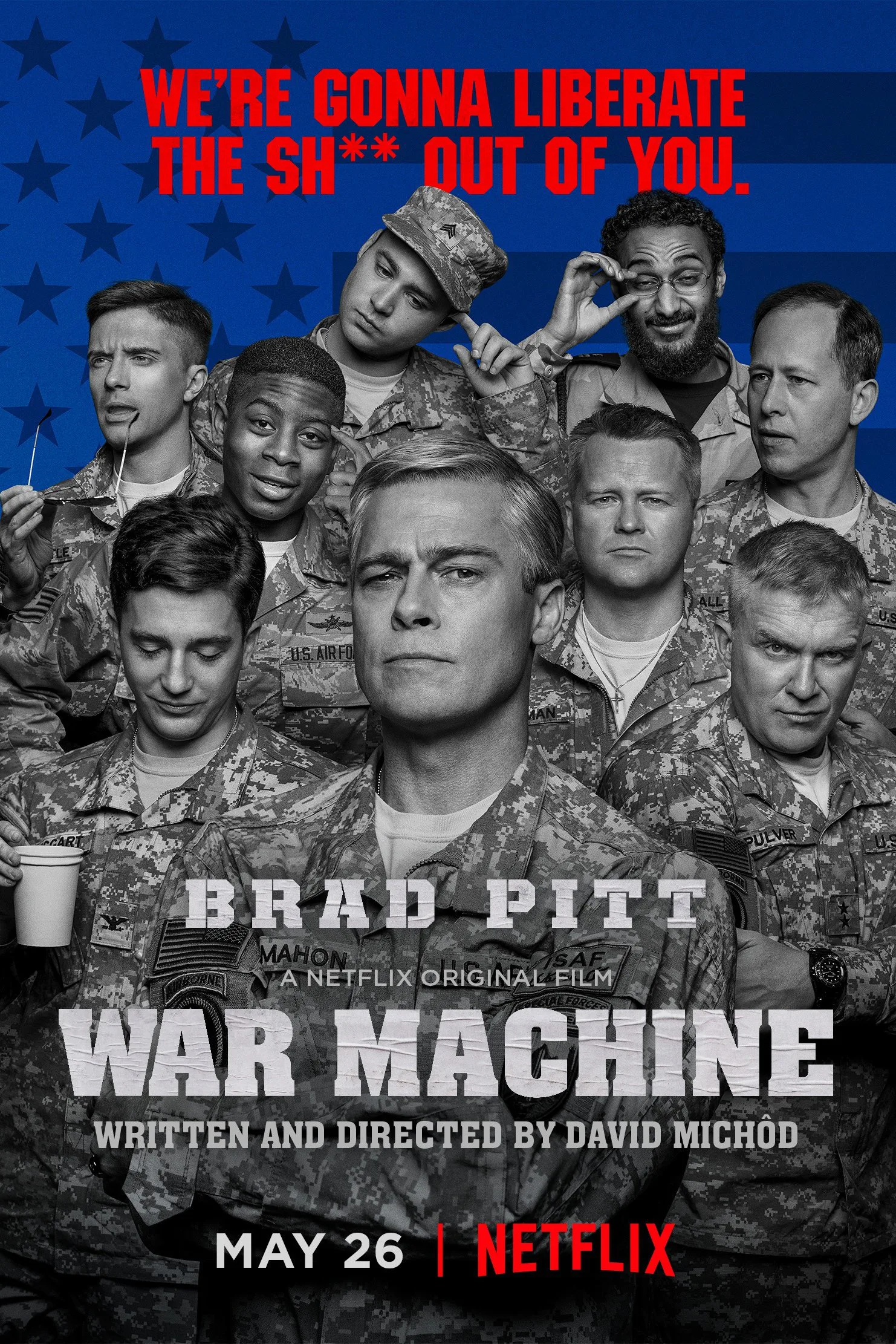

Brad Pitt plays General Glen McMahon as something of a heightened macho caricature—it’s a risky performance that has already divided audiences who saw the film at Cannes. In some scenes, it feels like a broad stereotype, an absurdist take on the determined war general with gritted teeth and square jaw. This is a guy who answers to the nickname “Glenimal,” a throwback to another era of war in a new era in which we call it a conflict instead. When McMahon is asked to advise on how to proceed in Afghanistan, it’s hoped that he’ll basically guide the pullout of troops from the area. He asks for 40,000 more. He’s told straight out that “You’re not here to win, you’re here to clean up the mess,” but McMahon didn’t become a soldier to clean up. He’s a leader with nowhere to lead people.

Michod tries to replicate his protagonist’s confusion and the general speedbumps of wartime bureaucracy through the structure of his film, which cuts together episodic moments in McMahon’s quest for validation and support. Consequently, while there are moments that really work—including an early disagreement with a soldier played by Keith Stanfield and a conversation on a plane with a suit played by Alan Ruck—they don’t link together in a coherent way. It’s a disjointed collection of scenes more than a film, as if Michod and Pitt never completely figured out what story they were trying to tell. On one hand, there’s something almost admirable about making a frustrating film about a frustrating time and person, and I do think some of the tonal inconsistencies are purposefully designed to relay that frustration to the viewer, but it makes for a disappointing experience overall. “War Machine” is one of those films that you keep waiting to get going, to figure out what it is, to start clicking. It never does.

Well, I should say it almost does. There’s a third act sequence that I won’t spoil that completely gets away from the conference tables and suits approach of the previous 90 minutes; it totally works and reminds one of the human cost of all of this nonsense. It’s what’s been missing from the rest of the movie, a sense of realism and relatability—Pitt’s broad choices, while admirable, never allow you to forget that this is a “performance.” And, again, it’s about the eighth movie within a movie that the overall incoherent “War Machine” becomes during its running time.