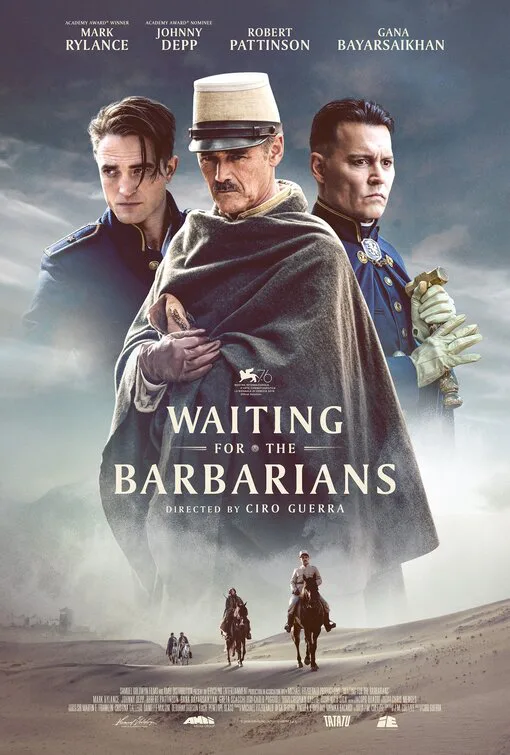

Mark Rylance had an easier time making us believe he was the 24-feet-tall “BFG” than he does here, trying to sell us a colonizer with a conscience in Ciro Guerra’s tedious “Waiting for the Barbarians.” The gentle actor plays a man here known as The Magistrate, the one guy in the 19th century British Empire who does not want to be cruel toward the nomads they’ve stolen the land from. There is a peace within The Magistrate’s small and unspecified corner of the empire, one that emanates from the quiet way he carries himself and chooses to help the nomads instead of locking them up. He even spends his nights trying to understand more of their language. If any colonizer could create a harmonious civilization, built on empathy but still following hierarchy, The Magistrate has done it.

In rides Johnny Depp’s supremely smug Colonel Joll, with his stiff posture, cryptic cheekbones, and large round black sunglasses that turn his face into a creepy void. He has arrived to obtain information from the nomads about a possible upcoming invasion, and he has different tactics than The Magistrate’s social work—he believes that torture leads to truth, and talks about the nomads like they are livestock with minimal significance. This conversation completely blows The Magistrate’s mind, so much that Guerra immediately cuts to him in a giant daze while trying to go about his activities, as if he had never really thought about it that way. That this one good apple is flabbergasted at how many bad apples are around him—the moment is meant to be a bold filmmaking choice, but instead it’s ridiculous. As he continues to wrestle with this weak inner turmoil, the movie’s pacing suffers, and so does its ability to keep our interest.

The Magistrate, despite the heartfelt way he approaches the world, is a novelty. When he’s told by fellow officers about plans to put pressure on the nomads in order to move them, The Magistrate laughs it off as if the guy had just told a joke. It’s sad that The Magistrate is such an anomaly, but it’s more sad that the game has clearly changed and he’s too clueless to get it. Any activist who has gotten into the fray will agree—such a lack of awareness to the problem at hand doesn’t help, and like with The Magistrate thinking that authoritarian forces will just stop and go home, it defeats one’s goals to be a good ally.

The Magistrate’s affection for the nomads is more seriously, and sweetly expressed toward a blinded woman (Gana Bayarsaikhan) that he meets and cares for in a middle passage in the film. He is protective of her, especially as she details the cruelty she experienced. His reaction to her story is incredibly sensitive, and a bit staggering, but proves that he’s probably in the wrong line of work: “What do you feel toward the men who did this to you?” In scenes that continue to drag the story away from a tangible plot, The Magistrate convoys through the desert to take her back to her people, giving cinematographer Chris Menges an opportunity to conjure some stunning vista shots, the most resonant feature of this handsome but often understated period piece. When The Magistrate returns, he sees that he has lost control; along with being called a traitor, he faces the implosion of all the good will he has built.

Even worse than the Magistrate’s naïveté is the fact that he’s a less believable character than Depp’s cartoonish Colonel Joll. But the movie, which has J.M. Coetzee adapting the 1980 book he wrote, believes The Magistrate is a real person, and believes in what he believes, and thus places us in his world. The editing takes after The Magistrate’s contemplative and delicate mindset, while Rylance’s performance seems to have taken acting cues from Jesus Christ, especially when he speaks calmly in between gruesome punishment. You can admire what the movie and Rylance alike are doing, but the film continues to ring false.

It’s not the nomads who are the barbarians, Guerra points out here, as like his previous time-spanning epics “Embrace of the Serpent” and “Birds of Passage,” which both depict brute modernity and indigenous cultures colliding at the intersection of survival. “Waiting for the Barbarians” would be a fitting title for a thesis about those recent films, so this movie should be a grand slam for the Colombian filmmaker working with his biggest production yet—instead it’s more revealing of how blunt his storytelling can be, and it’s almost as if having a larger budget and A-list cast has led him astray. Just as much as Depp’s approach to tackling such text is to be a black highlighter, Rylance might have been too easy a casting choice—there is so little nuance, even though Rylance makes it clear from the start how unusually kind The Magistrate is. Rylance and Depp play broadly drawn characters who represent two extremes of an argument, with Rylance’s khaki uniform sharply contrasted with Depp’s dark blue.

Robert Pattinson is also in this movie, and appears in this review in a similar fashion: toward the end, and barely of any importance. He plays an assisting officer to Colonel Joll who sometimes scowls and sometimes screams, and does little else. Given that the film was shot in 2018, when Pattinson had plenty of screen clout, you’re not sure how much of his footage is on the cutting room floor. But there is a clear sense of the movie trying to squeeze him into shots with Depp, or include cutaways shots despite Pattinson having nothing to say.

And yet giving approximately five minutes of screen-time to one of its biggest stars is not the worst way in which Guerra’s English-language debut defeats itself. This is a film that struggles to build an effective plot throughout its duration, with passages about scrounging for compassion in this fading world feeling as picturesque as they are hollow. The timely conversation topics are all there—the horrific act of othering, the damage of fear, the grave dehumanization that comes with lethal force—but “Waiting for the Barbarians” is too sentimental for the benefit of its larger ideas. Despite the sincerity that’s in every scene with Rylance’s performance, the movie’s good intentions remain wistful, and thoroughly frustrating.

Now available on digital platforms.