Vera Drake is a melodious plum pudding of a woman who is always humming or singing to herself. She is happy because she is useful, and likes to be useful. She works as a cleaning woman in a rich family’s house, where she burnishes the bronze as if it were her own, and then returns home to a crowded flat to cook, clean and mend for her husband, son and daughter, and cheer them up when they seem out of sorts. She makes daily calls on invalids to plump up their pillows and make them a nice cup of tea, and once or twice a week she performs an abortion.

London in the 1950s. Wartime rationing is still in effect. A pair of nylons is bartered for eight packs of Players. Vera (Imelda Staunton) buys sugar on the black market from Lily (Ruth Sheen), who also slips her the name and address of women in need of “help.” Lily is as hard and cynical as Vera is kind and trusting. Vera would never think of accepting money for “helping out” young girls when “they got no one to turn to,” but Lily charges 2 pounds and 2 shillings, which she doesn’t tell Vera about.

In a film of pitch-perfect, seemingly effortless performances, Imelda Staunton is the key player, and her success at creating Vera Drake allows the story to fall into place and belong there. We must believe she’s naive to be taken advantage of by Lily, but we do believe it. We must believe she has a simple, pragmatic morality to justify abortions, which were a crime in England until 1967, but we do believe it.

Some of the women who come to her have piteous stories; they were raped, they are still almost children, they will kill themselves if their parents find out, or in one case there are seven mouths to feed and the mother lacks the will to carry on. But Vera is not a social worker who provides counseling; she is simply being helpful by doing something she believes she can do safely. Her age-old method involves lye soap, disinfectant and, of course, lots of hot water, and another abortionist describes her method as “safe as houses.”

The movie has been written and directed by Mike Leigh, the most interesting director now at work in England, whose “Topsy-Turvy,” “High Hopes,” “All or Nothing” and “Naked” join this film in being partly “devised” by the actors themselves. His method is to gather a cast for weeks or months of improvisation in which they create and explore their characters. I don’t think the technique has ever worked better than here; the family life in those cramped little rooms is so palpably real that as the others wait around the dining table while Vera speaks to a policeman behind the kitchen door, I felt as if I were waiting there with them. It’s not that we “identify” so much as that the film quietly and firmly includes us.

The movie is not about abortion so much as about families. The Drakes are close and loving. Vera’s husband Stan (Phil Davis), who works with his brother in an auto repair shop, considers his wife a treasure. Their son Sid (Daniel Mays) works as a tailor, has a line of patter, is popular in pubs, but lives at home because of the postwar housing crisis. Their daughter Ethel (Alex Kelly) is painfully shy, and there is a sweet, tactful subplot in which Vera invites a lonely, tongue-tied bachelor named Reg (Eddie Marson) over for tea and essentially arranges a marriage.

“Vera Drake” tells a parallel story about a rich girl named Susan (Sally Hawkins), the daughter of the family Vera cleans for. Sally is raped by her boyfriend, becomes pregnant and goes to a psychiatrist who can refer her to a private clinic for a legal abortion. Like everyone in the movie, Sally is excruciatingly shy about discussing sex, and ignorant. “Did he force himself upon you?” the psychiatrist asks, and Sally is not sure how to answer. Leigh’s point is that those with 100 pounds could legally obtain an abortion in England in 1950, and those with two pounds had to depend on Vera Drake, or on women not nearly as nice as Vera Drake.

Vera’s world falls apart when the police become involved in an abortion that almost leads to death, and the tightly knit little family changes when the police knock on the door. The Detective Inspector (Peter Wight), is a considerable man, large, imposing, and not without sympathy. He believes in the law and enforces the law, but he quickly understands that Vera was not working for profit, and is not ungentle with her. In a courtroom scene, on the other hand, it is clear that the law makes no room for nuance or circumstance.

Some of the film’s best scenes involve the family sitting around the table, shell-shocked (after Vera whispers into her husband’s ear, telling him what he had never suspected). There are moments when Leigh uses his technique of allowing a reticent character to stir into conviction. At Vera’s final Christmas dinner, Reg, now engaged to Ethel, makes what for him is a long speech: “This is the best Christmas I’ve had in a long time. Thank you very much, Vera. Smashing!” He knows telling Vera she has prepared a perfect meal means more to her than any speech about rights and wrongs, although later he blurts out: “It’s all right if you’re rich, but if you can’t feed ’em, you can’t love ’em.”

“Vera Drake” is not so much pro or anti-abortion as it is opposed to laws which do little to eliminate abortion but much to make it dangerous for poor people. No matter what the law says, then or now, in England or America, if you can afford a plane ticket and the medical bill you will always be able to obtain a competent abortion, so laws essentially make it illegal to be poor and seek an abortion.

Even in saying that I am bringing more ideology into “Vera Drake” than it probably requires. The strength of Leigh’s film is that it is not a message picture, but a deep and true portrait of these lives. Vera is kind and innocent, but Lily, who procures the abortions, is hard, dishonest and heartless. The movie shows the law as unyielding, but puts a human face on the police. And the enduring strength of the film is the way it shows the Drake family rising to the occasion with loyalty and love.

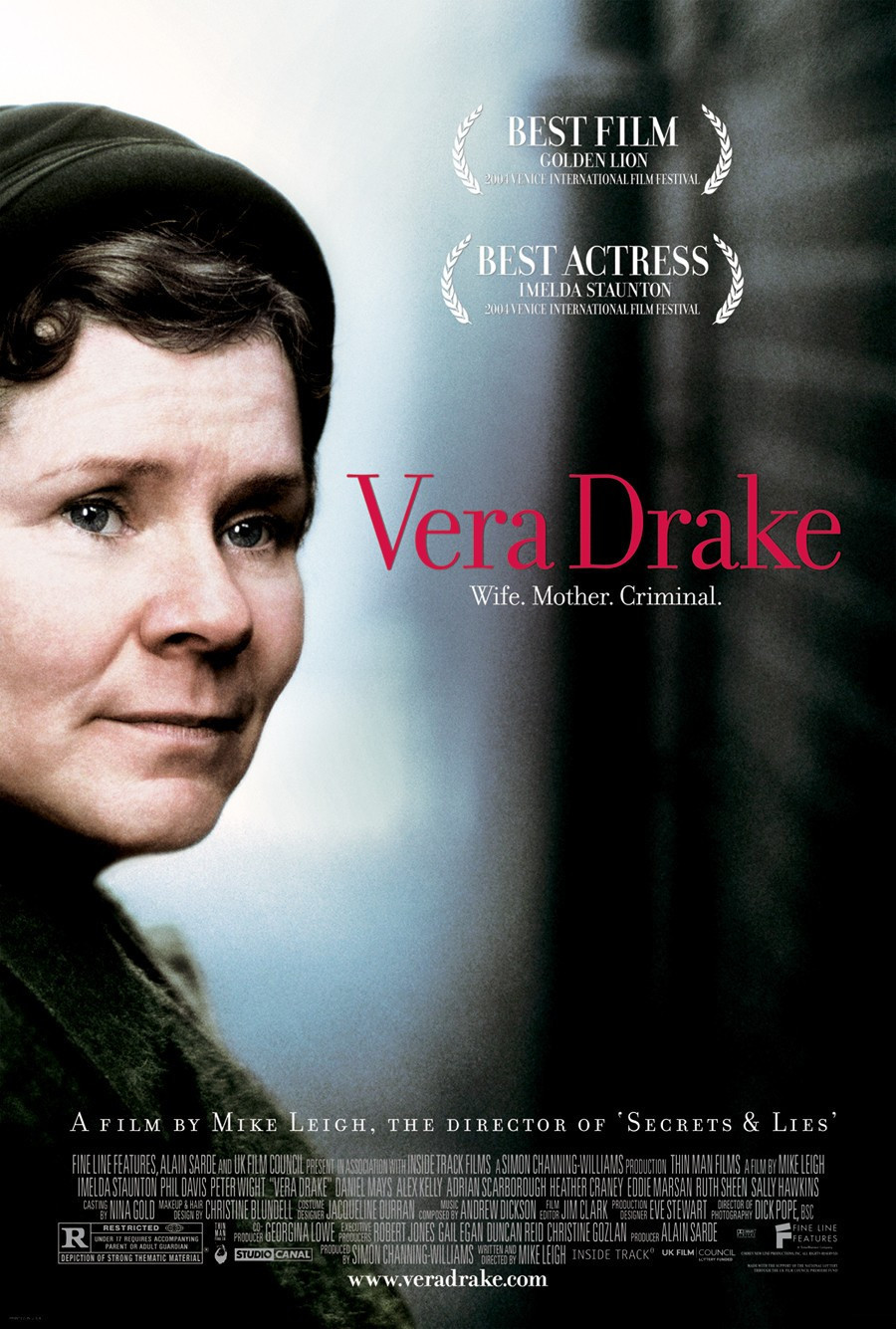

“Vera Drake” was named best picture and Imelda Staunton best actress at the Venice Film Festival. Oscar nominations will certainly follow.