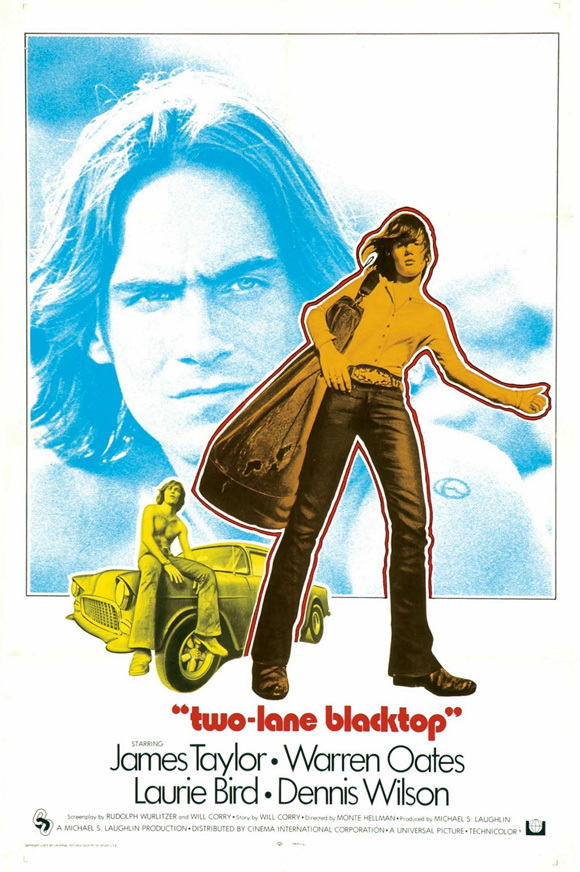

The girl simply turns up one day and gets into the back seat of the 1955 Chevy. She doesn’t seem to have a name, but then nobody else does, either. The driver and the mechanic drive away without even speaking to her, and that’s how they come to be together. A little further down the road, they run into G.T.O., so called because that’s the name of his machine, and they agree to conduct a cross-country race all the way to Washington. Winner gets the other car.

Monte Hellman’s “Two-Lane Blacktop” is mostly about this race, which is an odd race in that nobody much seems to want to win. The driver and the mechanic have devoted their lives to racing and winning with their customized and rebuilt Chevy, and G.T.O. identifies intimately with his car, yet they keep stopping to help each other along the road, as if the road would be unbearably lonely if that other car weren’t sometimes in view.

Their universe is one that’s familiar in recent American films like “Bonnie and Clyde,” “Easy Rider” and “Five Easy Pieces.” It consists of the miscellaneous establishments thrown up along the sides of the road to support life: motels, gas stations, hamburger stands. The road itself has a real identity in “Two-Lane Blacktop,” as if it were a place to live and not just a way to move. There may be homes and gardens hidden behind those interstate terraces, but for the four people in this movie — the road, as the saying goes, is home.

Hellman is an American director whose work is much prized by the French, who have a knack for finding existential truths in movies we thought were Westerns. I haven’t seen his earlier films (“Beast from Haunted Cave,” “The Shooting,” “Ride in the Whirlwind”), but this one is very personal. It seems to come from a single vision of the road, the race, and life; and, paradoxically, the characters need to be impersonal so they don’t interfere with this vision.

They are all too impersonal, though, and that’s bothersome. After half an hour or so, the fact that we’re told so little about their inner workings becomes a distraction. There doesn’t seem to be a good reason for making them so awesomely one-dimensional. Some critics complained that “Carnal Knowledge” limited itself too much to one layer of the characters’ lives; but “Two-Lane Blacktop” is even more specialized.

The movie is intended, I suppose, to be a metaphor. But unless I missed the point, it doesn’t have much of anything new to tell us. Sophomores in literary criticism could probably decode it as a metaphor involving the kinds of characters we meet, and our lack of communication with them, and yet our fundamental dependency on them, during life’s journey — but so what? Hardly anyone needs to be told that.

What I liked about “Two-Lane Blacktop” was the sense of life that occasionally sneaked through, particularly in the character of G.T.O. (Warren Oates). He is the only character who is fully occupied with being himself (rather than the instrument of a metaphor), and so we get the sense we’ve met somebody. That, and some of the racing and road scenes, and the visual texture of the movie, make it worth seeing.