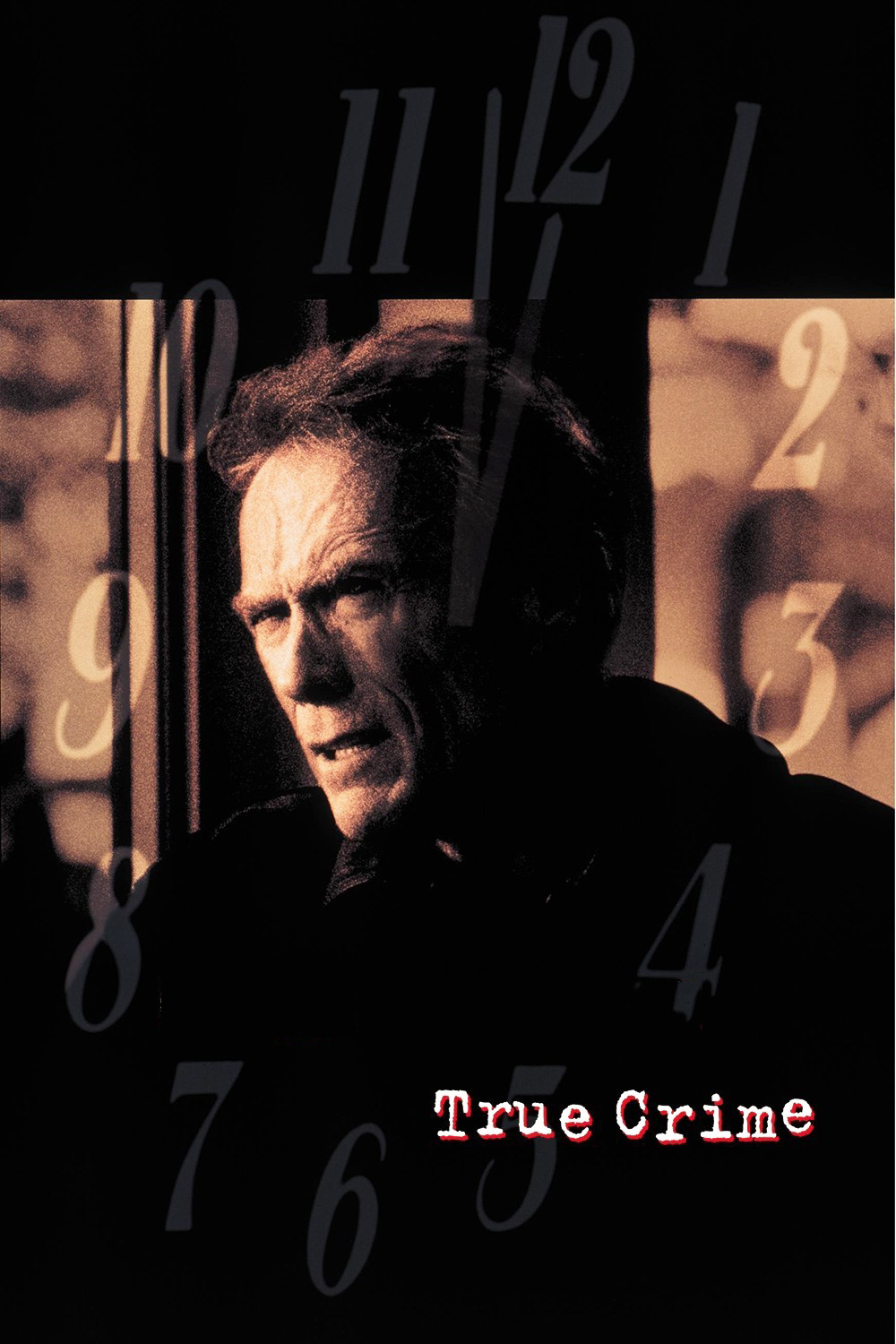

Clint Eastwood‘s “True Crime” follows the rhythm of a newspaperman’s day. For those who cover breaking news, many days are about the same. When they begin, time seems to stretch out generously toward the deadline. There’s leisure for coffee and phone calls, jokes and arguments. Then a blip appears on the radar screen: an assignment. Seemingly a simple assignment. Then the assignment reveals itself as more complicated. The reporter makes some calls. If there’s anything to the story at all, a moment arrives when it becomes, to the reporter, the most important story in the world. His mind shapes the form it should take. He badgers sources for the missing pieces. The deadline approaches, his attention focuses, the finish line is the only thing visible, and then facts, story, deadline and satisfaction come all at the same time. A deadline reporter’s day, in other words, is a lot like sex. Eastwood uses this rhythm to make “True Crime” into a wickedly effective thriller. He plays Steve Everett, a reporter for the Oakland Tribune. Steve used to work out East, but got fired for “screwing the owner’s under-age daughter.” The movie’s Web page says he worked for the New York Times, but this detail has been dropped from the movie, no doubt when the information about the owner’s daughter was added. Now he’s having an affair with the wife of Findley, his city editor (Denis Leary).

Everett’s personal life is a mess. His wife, Barbara (Diane Venora) knew he cheated when she married him, but thought it was only with her. Now they have a young daughter, but Everett seems too busy to be a good dad (there’s a scene where he pushes her stroller through the zoo at a dead run). Everett’s also a little shaky; he was a drunk until two months ago, when he graduated to recovering alcoholic. He’s assigned to write a routine story about the last hours of a man on Death Row: Frank Beachum (Isaiah Washington), convicted of the shooting death of a pregnant clerk in a convenience store.

Both the city editor and the editor-in-chief (James Woods) know Everett is a hotshot with a habit of turning routine stories into federal cases, and they warn him against trying to save Beachum at the 11th hour. But it’s in Everett’s blood to sniff out the story behind the story. He becomes convinced the wrong man is going to be executed. “When my nose tells me something stinks–I gotta have faith in it,” he tells Beachum.

This is Eastwood’s 21st film as a director and experience has given him patience. He knows that even in a deadline story like this, not all scenes have to have the same breakneck pace. He doesn’t direct like a child of MTV, for whom every moment has to vibrate to the same beat. Eastwood knows about story arc, and as a jazz fan, he also knows about improvising a little before returning to the main theme.

“True Crime” has a nice rhythm, intercutting the character’s problems at home, his interviews with the prisoner, his lunch with a witness, his unsettling encounter with the grandmother of another witness. And then, as the midnight hour of execution draws closer, Eastwood tightens the noose of inexorably mounting tension. There are scenes involving an obnoxious prison chaplain and a basically gentle warden, and the mechanical details of execution. Cuts to the governor who can stay the execution. Tests of the telephone hotlines. Battles with Everett’s editors. Last-minute revelations. Like a good pitcher, Eastwood gives the movie a nice slow curve and a fast break.

Many recent thrillers are so concerned with technology that the human characters are almost in the way. We get gun battles and car chases that we don’t care about, because we don’t know the people firing the guns or driving the cars. I liked the way Eastwood and his writers (Larry Gross, Paul Brickman and Stephen Schiff) lovingly added the small details. For example, the relationships that both the reporter and the condemned man have with their daughters. And a problem when the prisoner’s little girl can’t find the right color crayon for her drawing of green pastures.

In England 25 years ago, traditional beer was being pushed off the market by a pasteurized product that had been pumped full of carbonation (in other words, by American beer). A man named Richard Boston started the Real Beer Campaign. Maybe it’s time for a movement in favor of Real Movies. Movies with tempo and character details and style, instead of actionfests with Attention Deficit Syndrome. Clint Eastwood could be honorary chairman.