Grown men cry in “Trophy,” a documentary about the wildlife hunting industry. One is a manager at a big game preserve who takes tourists to shoot African elephants. He’s a big, tough-looking fellow, but as he talks about the emotional bonding that occurs between humans and animals, he bursts into tears, asks the filmmakers to cut, then leaves the frame, embarrassed. Another is a wildlife control officer and dedicated anti-poacher who sometimes has to kill exotic animals anyway because they’re threatening locals or endangering livestock. He seems to get choked up talking about the experience. “It’s an emotional thing, killing an animal,” he says, then goes on to speculate that for hunters, that emotion, and the accompanying rush of adrenaline, becomes an addiction that can only be satisfied by shooting more animals. This same movie starts with a Texas sheep breeder named Phillip Glass (no, not that one) helping his young son take down first buck. A ritual that may be horrifying to some is sacred to these two. Later, the father relates a childhood anecdote: when he was a boy, his mother warned him never to kill a redbird, and he immediately went out and did it anyway, and as he stared at the corpse, “I realized that I could not have loved that redbird more, even though it was dead.”

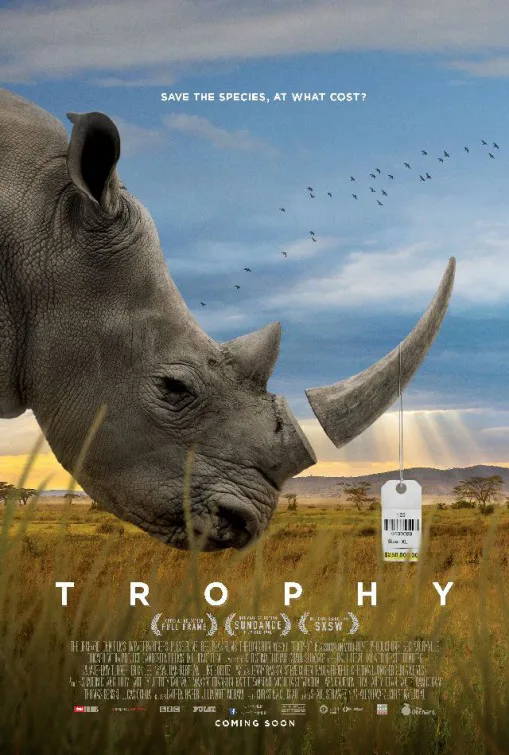

Evenhanded is not the right word for “Trophy,” a movie by Shaul Schwarz and Christina Clusiau (who are also the cinematographers). Though created with the latest moviemaking technology, including high-definition, lightweight cameras attached to drones, this is an old school documentary that considers an issue, the various people involved in it, and the communities and nations they inhabit. It is not a position paper but a work of curiosity and intelligence, filled with sublime and horrifying images. Shot with an ominously gliding camera that revels in the beauty of rhinos, elephants, lions and other rare animals and scrutinizes the map of each face that tells a story in front of it, “Trophy” strives to be kind and fair. But it is unmerciful in its exploration of the hunting business. Like a ruthless lawyer, it loves poking holes in arguments that appear rock-solid.

The mystical-sentimental justifications for killing penned-in animals are belied by footage of canned hunts—in particular one that ends with a ranch employee dragging a wounded crocodile from a man-made lake so that an American hunter can shoot it to death and shout, “Yeah, motherfucker!” (Before taking the kill shot, he pauses to put his beer down on the grass.) But there’s also acknowledgment throughout that you can’t just say “shooting animals is evil” and be done with it, because there are too many factors at play.

One is the existence of multibillion-dollar meat and egg industries built upon a foundation of prolonged, scientifically refined forms of torture. Some subjects in “Trophy” argue that if the only way to prevent African big game from going extinct is to transform them into glorified free-range farm animals, rarer but no less domesticated than sheep or cows, then that’s what should be done. “Give me [the name of] one animal that went extinct while farmers were breeding it,” asks South African rhino rancher John Hume. “There’s not one.” It may seem repugnant to use the profits derived from shooting animals to protect those same animals, but as Hume says near the start of the film, after watching his ranch hands drug a rhino and preemptively cut off its horn to make it unattractive to poachers, “If [this animal] had an opinion to give you, he would probably say ‘I’m happy to sacrifice my horn to save my life.'”

Then there’s the vise-grip of the global marketplace, which drives many poor Africans to poach for meat or to sell prized trophies (such as rhino horns) on the black market, where they can fetch a higher price per gram than heroin or gold. Every decision made in relation to hunting affects someone, often adversely. The lingering stench of colonialism hovers over every sentence uttered onscreen.

One long, wrenching sequence in “Trophy” shows a white anti-poacher leading a team onto a nearby farmhouse to look for a black man suspected of poaching, then intimidating a group of young suspected poachers by warning them that if they keep doing this, they could end up getting shot by somebody like him. But the visuals in these scenes and others are politically charged, in ways that the filmmakers seem keenly aware of. In Africa, in North America, everywhere, it’s usually white people (on both sides of the issue) telling black people, often poor ones, what they can or can’t do with wild animals. As sympathetic as we might be towards exotic creatures and the humans who adore them, it’s still chilling to see a beefy white man barge into a tiny black woman’s house in the middle of the night, shine a flashlight in her face, and force her to lie in the dirt while he interrogates her. “He’s a bad guy, and he’s done bad things,” the wildlife officer says of her husband. “Please don’t beat me,” she asks.

The movie seems like a roughly assembled collection of scenes, arranged in an “on the one hand/on the other hand” manner. But if you pay attention not just to what’s being said but how the film is structured and which sentiments get repeated, you realize that the filmmakers are building rather masterfully towards a central argument that encompasses every person and point-of-view. This entire story is about capitalism run amok. Whatever makes money is going to happen one way or another, no matter what laws are passed, no matter what lofty sentiments are expressed, no matter what justifications people on various sides of an issue give for whatever they believe. What’s ultimately at stake here is the question of whether “the commodification of wildlife,” as one activist puts it, is morally much worse than the commodification of everything else on the planet, including human life—and whether we need to be less idealistic about solutions, now that we appear to be barreling towards some kind of global political and environmental reckoning.

The human species has been altering, processing, consuming and destroying nature to suit its own ends, often with specious religious or political justifications, since the dawn of civilization. The technology has just become more efficient. The recent push to restrict or end hunting is occurring against the backdrop of a natural landscape that might have ceased to exist without the subsidies of hunters and people catering to hunters, the same group whose urge to kill thinned the rhino population from 500,000 in 1900 to about 30,000 today. And some believe that the only way to keep rhinos and other species alive is to continue catering to the same humans who nearly wiped them out.

This may seem like a horrendous conundrum, but it’s real, it’s not going away, and a good part of the running time of “Trophy” is dedicated to exploring it. Ecologist Chris Packer tells the filmmakers that he thinks canned hunts are less defensible than the European and American-dominated safaris that thinned the African game population a hundred years ago, because prior generations of hunters would track a lone animal through the jungle or across the plains for weeks, while rich tourists might shoot several animals at once on a ranch, so fast that their beer is still cold when they pose for celebratory pictures. But if you’re killing an animal with a gun, often from so far away that it doesn’t even know you’re there, why be incremental with your condemnation or approval? If rhinos, elephants, lions and the like are almost certain to be wiped out by poachers if controlled hunting isn’t allowed, then shouldn’t societies allow it?

Outside of a safari industry convention in Las Vegas, a protester holds up a sign that reads “Killing isn’t conservation.” But it is. The entire running time of “Trophy” is dedicated to examining how both sentiments can be true. This is a brilliant, maddening, necessary movie.