I started reading Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman in 1965, and intend to finish it any day now. That is true, and also a joke (a small one) involving a novel about procrastination. Tristram Shandy begins with its hero about to be born and becomes so sidetracked by digressions that the story ends shortly after his birth. Perhaps Sterne considered writing a sequel describing the rest of Tristram’s life, but never got around to it (smaller joke).

Now comes “Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story,” the movie, which never gets around to filming the book. Since the book is probably unfilmable, this is just as well; what we get instead is a film about the making of a film based on a novel about the writing of a novel. As an idea for comedy this is inspired, and Michael Winterbottom and his screenwriter, Frank Cottrell Boyce, show the filmmakers constantly distracted by themselves. “But enough about me,” Darryl Zanuck once said. “What did you think of my movie?”

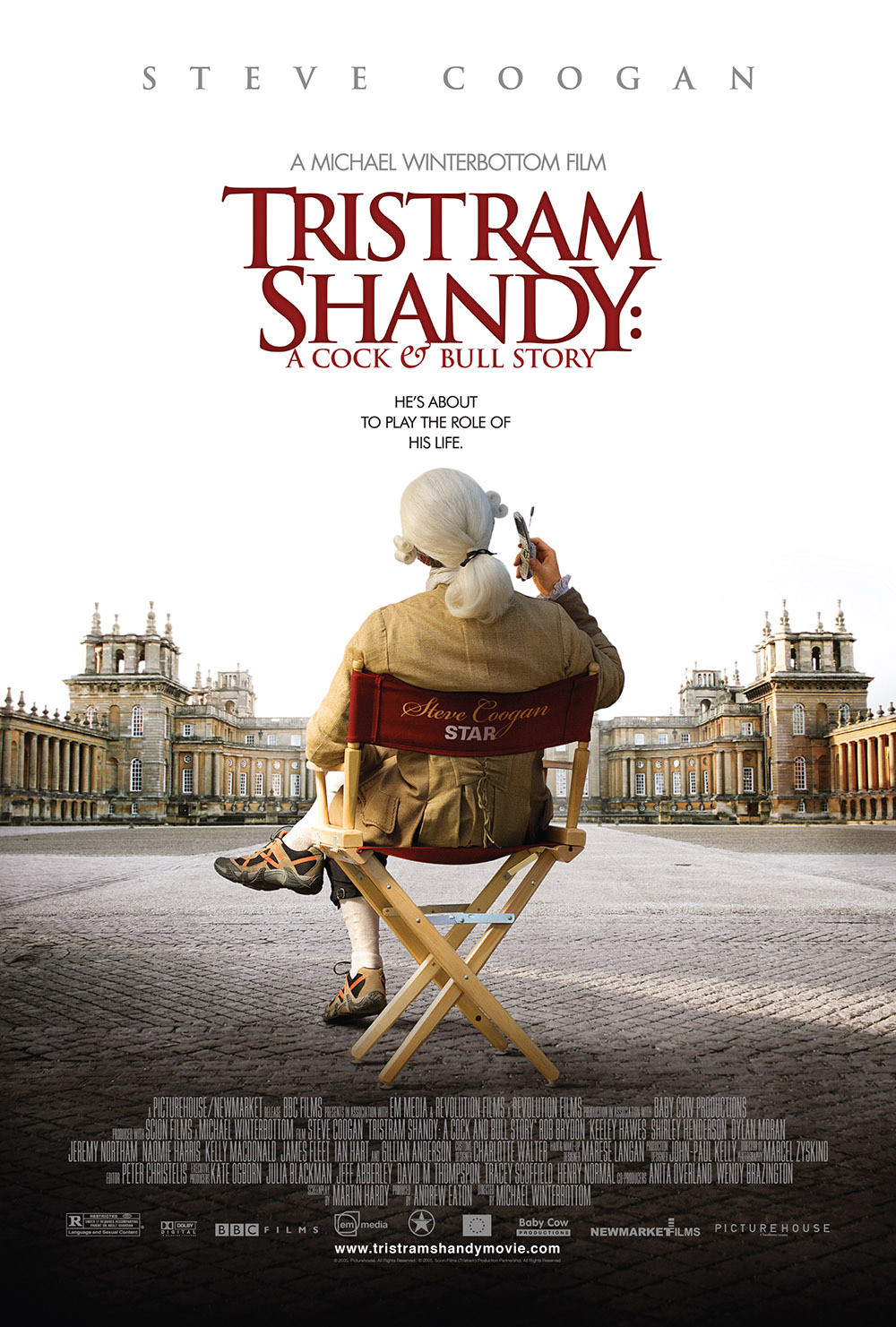

The film takes place on the set of a movie named “Tristram Shandy.” It involves actors named Steve Coogan, Rob Brydon, Gillian Anderson and others, played by Steve Coogan, Rob Brydon, Gillian Anderson and others. The opening scene takes place in a makeup room, where Coogan and Brydon discuss their billing, and whether Brydon’s teeth are too yellow. Coogan has the lead, playing both Tristram and his father, Walter. Brydon plays Tristram’s uncle Toby, who devotes his life to constructing a large outdoor model of the battlefield where, as a young man, he suffered an obscure wound. The Widow Wadman (Anderson), who is considering marrying Toby, wants to know precisely how and, ahem, where he was wounded. “Just beyond the asparagus,” Toby explains, pointing to his model landscape.

But I digress. Back to the dressing room. Coogan mentions that he has the lead in the movie. Yes, says Brydon, but Toby is “a featured co-lead.” Coogan: “Well, we’ll see after the edit.” Both actors are competitive in that understated British way that involves put-downs hardly less obscure than Toby’s wound. Coogan wants the wardrobe department to build up his shoes so that the “featured co-lead” will not be taller than the leading man. Brydon learns that Gillian Anderson has been hired to join the cast, and is panic-stricken: He is afraid that in a love scene he might blush, or be betrayed by stirrings beyond the asparagus.

There are elements of “This Is Spinal Tap” in the film, and also a touch of Al Pacino’s “Looking For Richard,” a semi-documentary about actors preparing to play Richard III. From “Spinal Tap” come the egos of the artists and the shabbiness of their art; from Pacino the film borrows the device of explaining the material to the viewers while it is being explained to the actors (only one person in “Tristram Shandy,” and possibly nobody in the audience, has read the book).

The art is endearingly shabby. There is a screening of some battle footage in which lackluster foot soldiers wander dispiritedly past the camera, looking like extras on their lunch break. And a scene in which a miniature unborn Tristram is seen inside a miniature womb; I was reminded of Stonehenge in “Spinal Tap.” The explanations of the material include witty dinner-time conversation by Stephen Fry, playing himself playing an actor playing a literary theorist. Coogan picks up enough to lecture an interviewer: “This is a postmodern novel before there was any modernism to be post about.” Later it’s claimed that Tristram Shandy was “No. 8 on the Observer’s list of the greatest novels,” which cheers everyone until they discover the list was chronological.

Now about that interviewer. He has information about a lap dancer that the actor met one recent drunken evening. It would be embarrassing to see the lap dancer on the front page of the tabloids, but the interviewer is willing to do a deal: He’ll tidy the story in return for an exclusive about Coogan’s relationship with his girlfriend Jenny (Kelly MacDonald), who has just given birth to their baby. It would not be good for Jenny to read about the lap-dancer.

Jenny, as it happens, has just arrived on the set, where Coogan has been having a flirtation with a production assistant named Jennie (Naomie Harris). Jennie is not merely sexy and efficient, but a film buff who offers analysis and theory to people who really only want a drink. She compares the ungainly battle scene to Bresson’s work in “Lancelot du Lac,” and has a lot to say about Fassbinder, who Coogan vaguely suspects might have been a German director. Not surprisingly, Jennie is the only person on the set who has read the novel, and tries to explain why the battle scene isn’t exactly important.

Because their work is so varied, the director Winterbottom and Boyce, his frequent writer, are only now coming into focus as perhaps the most creative team in British film. Their collaborations include films as different as “Butterfly Kiss,” “Welcome To Sarajevo” ,” “The Claim,” “Code 46” and “24-Hour Party People.” That the same director and writer could make such different films is almost inexplicable, and consider too that Winterbottom directed “Wonderland” (2000) and Boyce wrote Danny Boyle’s “Millions.”

Boyce told me “Tristram Shandy” might sound a little like Charlie Kaufman’s screenplay for “Adaptation,” but he thinks it’s closer to Truffaut’s “Day for Night” (am I sounding a little like Jennie here?). It wonderfully evokes the life on a movie set, which for a few weeks or months creates its own closed society. Wives and lovers visit the set but are subtly excluded from its “family,” and even such a miraculous creature as a newborn baby is treated like a prop that is very nice, yes, but not needed for the scene. As the final credits roll, Coogan and Brydon are still engaged in their running duel of veiled insults. They are briefly diverted, however, by imitating Pacino as Shylock. Every actor knows what David Merrick meant when he said, “It is not enough for me to succeed; my enemies must fail.”