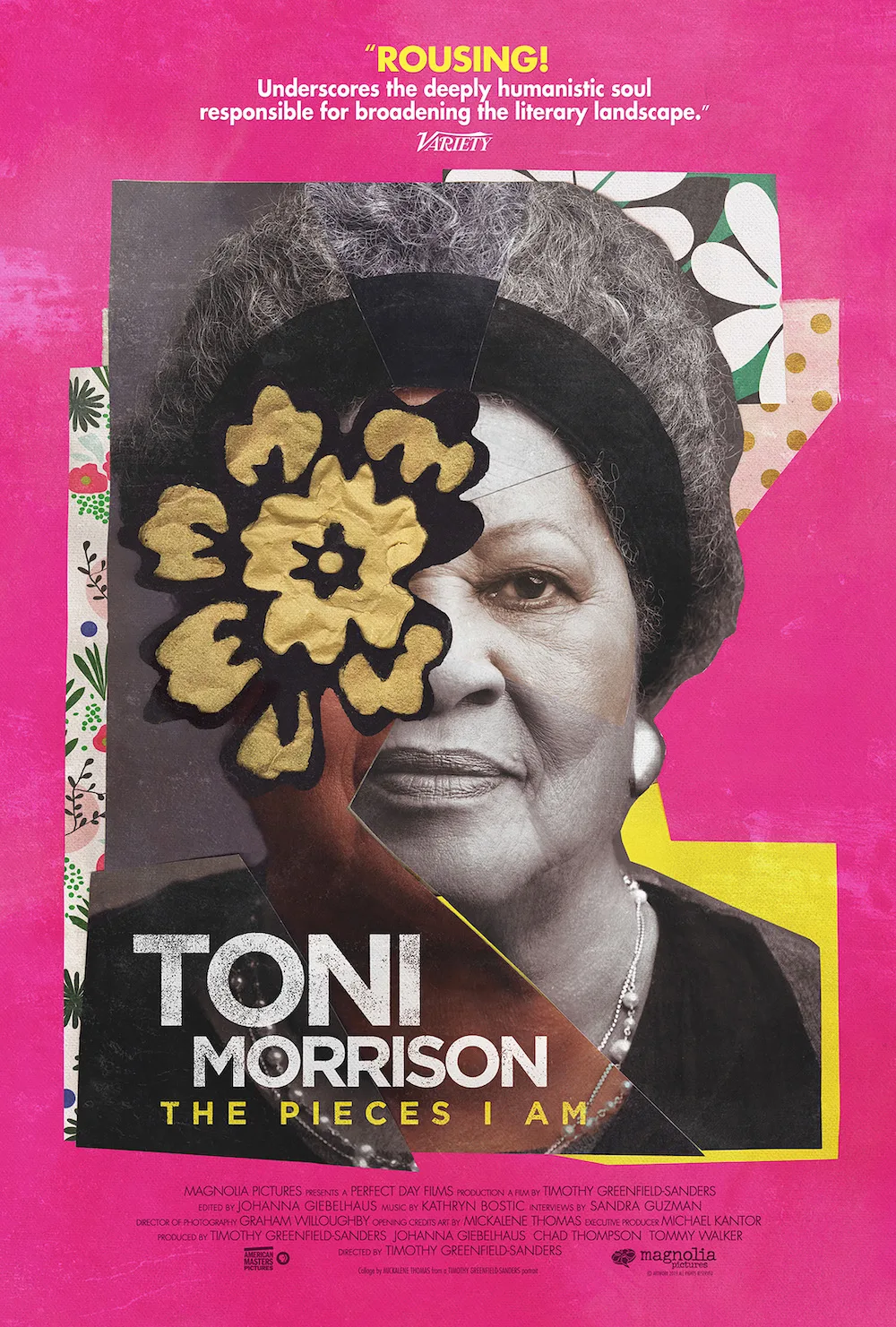

We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here. “Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am” is now streaming on Hulu, and available for rental at a discount price. #BlackLivesMatter.

Within minutes of Timothy Greenfield-Sanders’s new documentary “Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am,” it’s obvious that the distinguished author is a born storyteller. Her words are precious, perfectly placed in her melodic speech. Even her childhood memories come off as tiny epics, revealing some part of her, and by extension, some part of us in the process. Her reverence and awe at the power of the written word are as strong as ever. With a knowing smile, she revisits her memories in one-on-one style interviews, looking directly at the camera—at us—to tell her story. A chorus of scholars, critics and friends join her to sing praises for her work that she’s too modest to bring up herself.

Today, we know Toni Morrison as a Nobel Prize-winner, a staple on high school reading lists, and the occasional target of a book ban. But even as a child, she noticed the world around her differently. In the documentary, she remembers her grandfather bragging about having read the Bible five times. She thought it odd, but later, she would recognize that in his time, it was illegal for Black people to read, so his accomplishment was an act of subversion and instilled in her the feeling that the written word mattered. Morrison also recalled the childhood memory of a Black girl her age who prayed for blue eyes. She realized that the pain the girl was in was caused by generations of racism. That memory would become the basis for her first book, The Bluest Eye.

Throughout the documentary, its subjects explain the impossible barriers Morrison faced in her career, including the literary establishment who undervalued her abilities and the financial challenges as a single mother. White critics lamented her insistence on centering the Black experience, like when the New York Times declared Morrison too talented a writer to “remain a recorder of black provincial life” in its review of her second book, Sula. Morrison is later shown batting away similarly ignorant questions about her work in older interviews. Almost immediately in the documentary, she addresses the white gaze and explains with the patience of a teacher why whiteness was assumed to be the norm and why her work was so threatening to those assumptions. She touches on craft, her writing routine and how she writes about the Black experience for an audience that doesn’t need it spelled out for them.

Among the voices of admirers are fans and friends Oprah Winfrey, Angela Davis, Fran Lebowitz, and Sonia Sanchez. It’s an incredible array of testimonies, but I wish it went beyond unbridled platitudes. These are deeply sharp women, and I know they have more to say about Morrison’s work, like Oprah, who not only championed her books on her TV show, she produced the film of Morrison’s unflinchingly raw novel “Beloved,” but these moments pass by quickly in the film. Davis mentions how Morrison brought up other Black writers at Random House, where she worked as an editor, but her interview stops short of what it meant that not only did she succeed in this field but also opened doors for others. There is not a word of criticism of Morrison’s work that isn’t meant to be scorned at for its shallow, racist conclusions, which gives the documentary a very positive tone but feels like an incomplete portrait of a complex artist who did not hold back from confronting the worst of human history and its present.

Greenfield-Sanders, a documentarian known for working on the HBO anthology series like “The Latino List,” “The Out List” and “The Trans List,” is used to compiling different strands of stories into one greater tapestry. One issue with this approach is its stop-and-go nature of jumping from archival photos and television interviews to those taken in a present-day photo studio. Interspersed throughout the interviews are examples of Black art that illustrate things mentioned in Morrison’s books or in others’ anecdotes. The collection is impressive and thoroughly researched, but the extra additions slow the rhythm of this story just enough to lose some momentum.

Still, the documentary has the power to introduce Toni Morrison to a new generation of readers and share new stories with longtime fans. We get an empowering impression of the woman behind those words. We get a deeper appreciation of what it means for her to have published books and have them resonate with audiences. And we get a better sense of the behind-the-scenes struggles Morrison won against pay inequality and discrimination. Morrison’s legacy is more than just the titles on a reading list, and this documentary will likely help many viewers see just how monumental her accomplishments remain.

“Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am” is now streaming on Hulu, and available for rental at a discount price.