I denounced “The Mummy Returns” for abandoning its characters and using its plot “only as a clothesline for special effects and action sequences.” Now I recommend “Time and Tide,” which does exactly the same thing. But there is a difference. While both films rely on nonstop, wall-to-wall action, “Time and Tide” does a better job, and plugs its action and stunt sequences into the real world with everyday props, instead of relying on computers to generate vast and meaningless armies of special effects creatures.

It’s one thing to create an Egyptian canine sand warrior on your computer, multiply it by 1,000, and send the results into battle. It’s another thing to show a man rappelling down the sides of the interior courtyard of a high-rise apartment building, with the camera following him in a vertiginous descent. In “The Mummy Returns,” you’re thinking of the effects. In “Time and Tide,” you’re thinking you’ve never seen anything like that before.

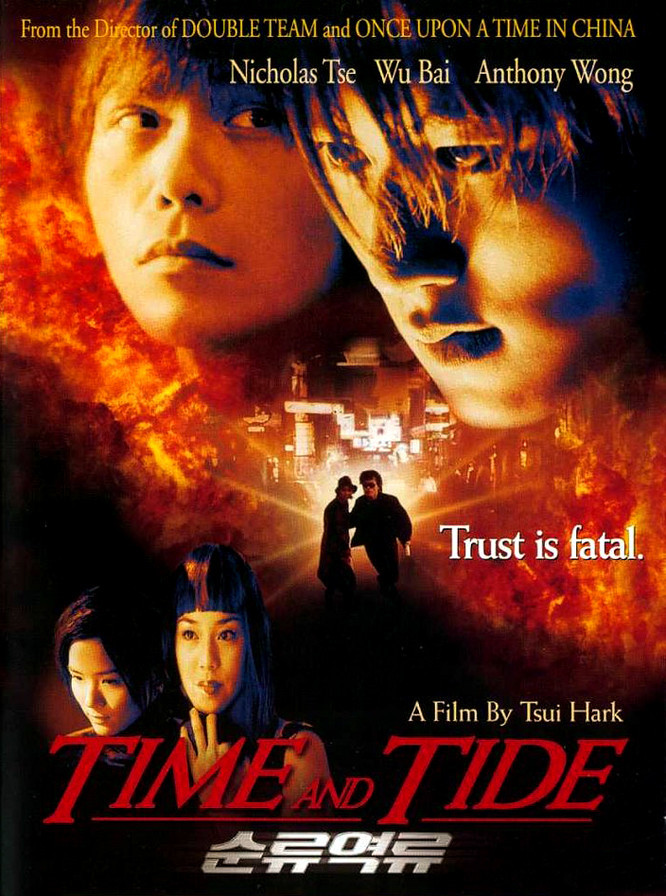

“Time and Tide” is by Tsui Hark, a master of the martial arts action genre, returning to his Hong Kong roots after a series of Hollywood-financed co-productions starring Jean-Claude Van Damme. To describe its plot would be futile. No sane moviegoer should expect to understand most of what happens from a narrative point of view, beyond the broadest outlines of who is more or less good, and who is more or less bad.

In general terms, the hero Tyler (Nicholas Tse) is trapped in a war between two drug cartels, while simultaneously tracking a lesbian policewoman named Ah Jo (Cathy Tsui), who was made pregnant by Tyler during an evening neither one can quite remember. The situation is further complicated by Tyler’s friendship with the older mercenary Jack (Wu Bai), who has returned from adventures in South America and has also impregnated a young woman.

That gives us two roughly parallel action strands, populated by characters who look confusingly similar at many moments because we get only glimpses of them surrounded by frenetic action. Does Tsui Hark know this? Yes, and I don’t think it bothers him. This is the man whose command of his genre helped make Jet Li into a star, and whose range also encompassed the legendary fantasy “A Chinese Ghost Story.” “Time and Tide” is essentially a hyperactive showcase for Tsui Hark’s ability to pile one unbelievably complex action sequence on top of another. Characters slip down the sides of parking garages on fire hoses, they crash through plate glass windows, they roll out of range of sprays of machinegun fire, they are pulled down staircases by ankle chains, they engage in chases involving every conceivable mode of transportation, and there is a sequence near to the end where Tyler assists Ah Jo in giving birth while she uses his gun to fire over his head at their attacking enemies.

Who is Tsui Hark (pronounced “Choy Huck?”). After more than 60 features, he is the Asian equivalent of Roger Corman, I learn from a New York Times profile by Dave Kehr. He was born in Vietnam in 1951 when it was under French rule, emigrated to Hong Kong at 15, later studied at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and edited a newspaper in New York’s Chinatown. “From the beginning,” Kehr observed, “Mr. Tsui was always willing to go a little bit further than his colleagues.” He “was an instinctive postmodernist for whom style was its own justification. [He] created a cinema meant to appeal to the eye, ear and skin far more than to the brain.” Certainly my eyes, ears and skin were more involved than my brain as I watched “Time and Tide,” and that explains why I liked it more than “The Mummy Returns,” even though both films could be described as mindless action adventures. With “The Mummy Returns,” I was repeatedly reminded that one extravagant visual sequence after another was being tied together with the merest of plot threads, which even the actors treated in a semi-ironic fashion. With “Time and Tide,” the plot might be as tenuous, but the actors treat it with ferocious seriousness (whatever it is), and the presence of flesh-and-blood actors and stunt people create an urgency lacking in the obviously fabricated “Mummy” effects.

After that childbirth-and-gunfire sequence near the end, there’s one on which the newborn infant, in a small wooden box, is thrown through the air to save its life. As matters of taste go, is that more defensible than the scene in “Freddy Got Fingered” where Tom Green whirls the newborn infant around his head by its umbilical cord, saving its life? Yes, I would say, it is (the modern film critic is forced into these philosophical choices). It is defensible because there is a difference between thinking, “This is the grossest moment I have ever seen in a movie” and “Gee, I hope the kid survives!”