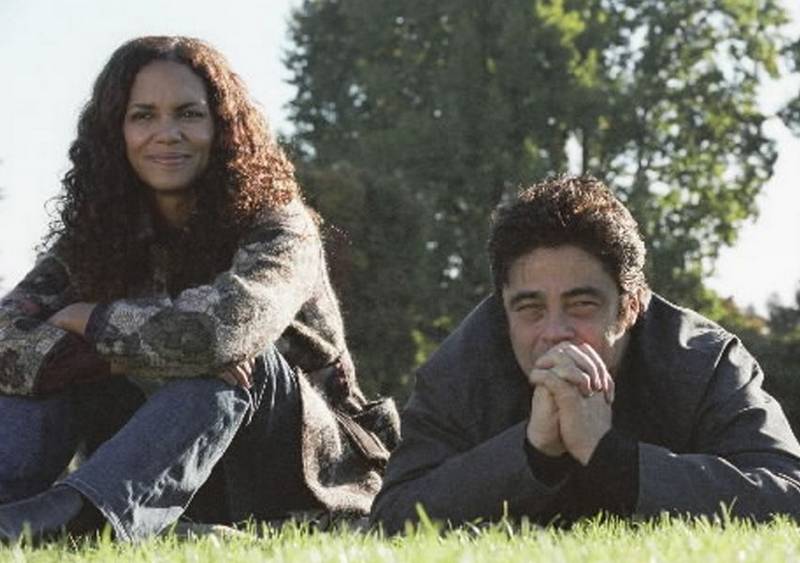

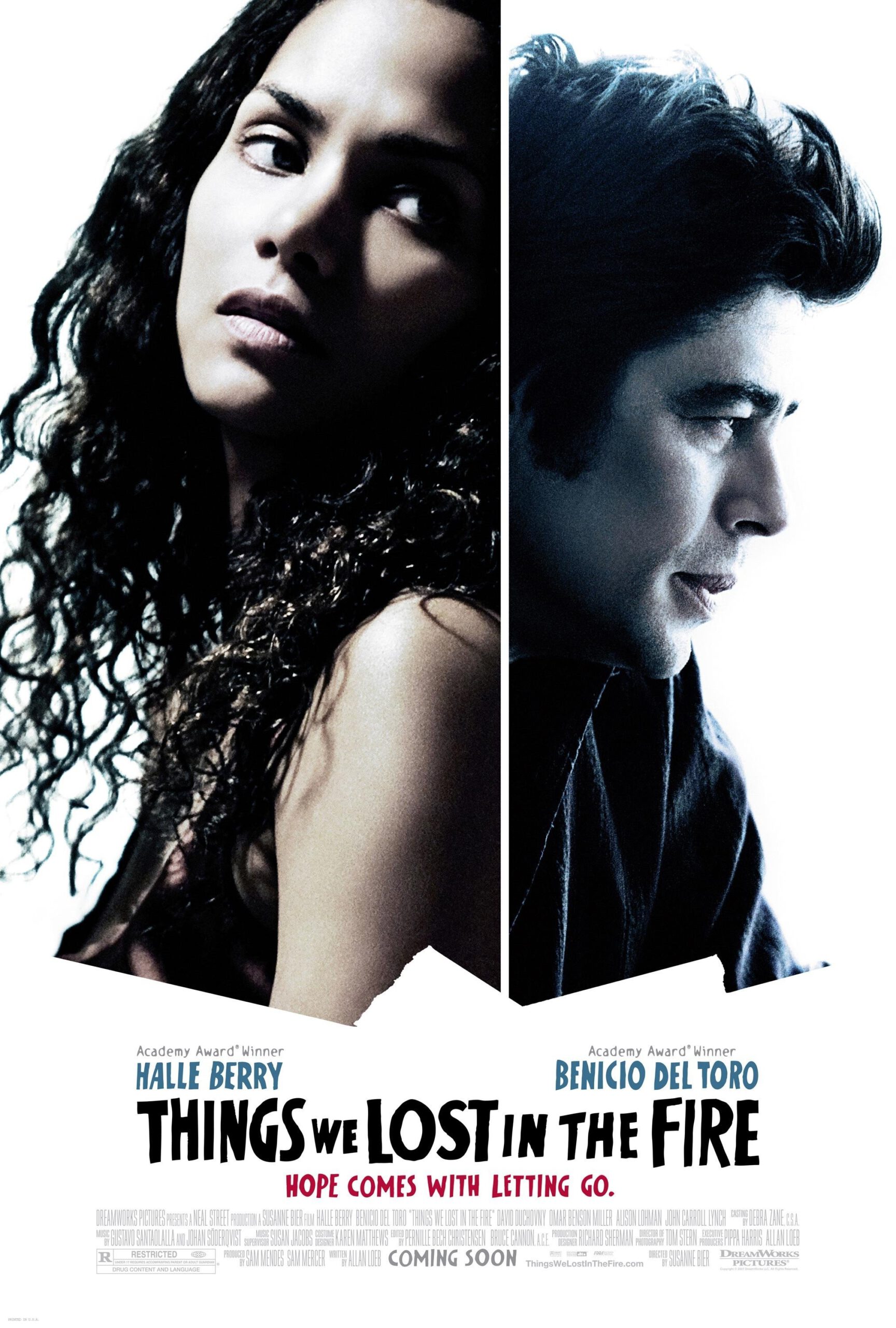

There is one man at the wake who doesn’t seem to belong. Scruffy, unshaven, smoking, uncomfortable with himself, he draws aside from the affluent friends of the deceased. Yet he was the dead man’s best friend. Jerry Sunborne (Benicio Del Toro) was never approved of by Audrey Burke (Halle Berry), the new widow, but she has invited him to the funeral all the same. She knows her husband would have wanted her to.

As “Things We Lost in the Fire” opens, Audrey was married for 11 years to Brian Burke (David Duchovny, seen in several flashbacks), and they were happy years, giving her two children, now 10 and 6, and a big house in an upscale suburb. Brian was a “genius” at real estate deals, her lawyer tells her, and she has inherited a fortune. But her loneliness haunts her. In a way, it was Jerry’s “fault” that her husband died, because he visited his friend’s flophouse on his birthday and was killed in a senseless street crime while trying to stop a stranger from beating his wife.

But that was like Brian, being loyal to his friend and playing a good Samaritan. Jerry and Brian were friends from childhood; Jerry became a lawyer, and then a drug addict, and is now trying to get clean and sober at Narcotics Anonymous. And Audrey surprises herself by inviting him to come and live with them, in a room in the garage.

No, she’s not thinking of falling in love with Jerry — far from it — but she knows her husband would be pleased to see his friend in a safe place, and after all Audrey and Jerry loved Brian more than anyone else in the world.

The film, directed by the talented Danish filmmaker Susanne Bier, centers on these two damaged people, who do not precisely help each other recover, but at least do not feel so alone. The screenplay by Allan Loeb is a first feature effort, but he has six more films in the works, including one announced by Ang Lee. Loeb is good at following the parallel advances and setbacks of his characters, and especially good at depicting how the children, 10-year-old Harper (Alexis Llewellyn) and 6-year-old Dory (Micah Berry, no relation), relate to the newcomer with resentment, then dependence, then uncertainty. The movie also accurately watches how a 12-step group works, especially in the character of the member Kelly (Alison Lohman), who keeps an eye on Jerry and alerts Audrey to a relapse.

Another affecting supporting performance is by John Carroll Lynch, as a tactful neighbor who steers Jerry toward a real-estate agent’s license.

The key performance in the film is by Del Toro, who never overplays, who sidesteps any temptation to go over the top (especially in scenes of his suffering), and whose intelligence as a one-time lawyer shows through his street-worn new reality. He is puzzled and surprised that Audrey invites him into her home, but with his options, it’s the best offer he’ll ever receive. There is only one scene between them that is ill-advised, and indeed unbelievable, and you’ll know the one I mean.

Bier has made two films I greatly admired, “Open Hearts” (2002) and “Brothers” (2005), but in her American debut she gets a little carried away with style, and especially with closeups, and very especially with closeups of eyes. I’ve never see this many great big eyes in a film: Berry’s beautiful, Del Toro’s bloodshot, the kids’ twinkling or doubtful. The human face is the most fascinating subject for the camera, as Ingmar Bergman taught us, but its elements out of context can grow lonely.

I suppose we could be dubious about a great beauty like Halle Berry seeming to be unaware of the strangeness of asking a heroin addict to live in her garage. But I accepted her decision as motivated by a correct reading of what her husband might have wanted her to do. That question settled, the movie is an engrossing melodrama, and it has its heart in the right place.