Jannik has always been the embarrassment of the family, an aimless younger brother who, as “Brothers” opens, is being released from prison after committing a crime hardly worth his time and effort. Was he breaking the law simply to play his usual role in the family drama?

Michael is the good brother, a loving husband, a responsible father, a man who does his duty. When his Danish military unit is sent to Afghanistan, he goes without complaint, because he sees it as the right thing to do. Within a shockingly short time, his helicopter is shot down, and his wife Sarah is told he was killed.

Jannik, with no better choice, tries to do what he sees as his duty: To be kind to Sarah, to be a good uncle to the children, to help around the house. In subtle ways that are never underlined, he starts acting from a different script in his life; with Michael gone, a vacancy has been created in the family, and Jannik steps into it. Now he is the person you can trust.

It is not a spoiler to reveal that Michael was not killed in the helicopter crash, but captured by Afghan enemies. This is made clear very early; the movie is not about mysteries and suspense, but about behavior. As a prisoner he is treated badly, but his real punishment comes when his captors force an impossible choice upon him. If he wants to save his own life, he will have to take the life of a fellow prisoner, a man he likes, who is counting on him.

Strangely enough, this is the second movie this weekend with a choice between evils. In Paul Schrader’s “Dominion,” a priest is told that if he doesn’t choose some villagers to be killed, the whole village will die. Michael’s choice is more direct: Either he will die, or the other prisoner will. In theory, Michael should choose death. Not so clear is what the priest should have done; theology certainly teaches him to do no evil, but does theology account for a world where good has been eliminated as a choice?

Michael saves his own life; let the first stones be cast by those who would choose to die. Eventually he is freed and returns home, to find things somehow different. He is no longer able to subtly condescend to his screwed-up little brother, because Jannik has changed. And Michael has changed, too. Sarah senses it immediately. There is a torment in him that we know is an expression of guilt.

It shows itself in strange ways: In his anger, for example, about the new kitchen cabinets that Jannik installed in his absence. In the love the children have for their uncle. And in Michael’s own relentlessly growing jealousy. “It’s all right if you did,” he tells his brother, “since you both thought I was dead. But I have to know: Did you make love?”

The answer to the question is simple (and perhaps not the one you expect). The meaning of the answer is very tricky, because Michael is a time bomb, waiting to explode. He has lost his view of himself in Afghanistan, and back at home in Denmark he cannot find it again, perhaps because the way is blocked by Jannik.

The movie was directed by Susanne Bier, who wrote a story that was turned into a screenplay by Anders Thomas Jensen. They worked once before, on “Open Hearts” (2003), the story of a couple engaged to be married when the young man is paralyzed from the neck down in a senseless accident. Will she still love him? Will she stay with him? How does he feel about that? Bier and Jensen are drawn to situations in which every answer leads to a question.

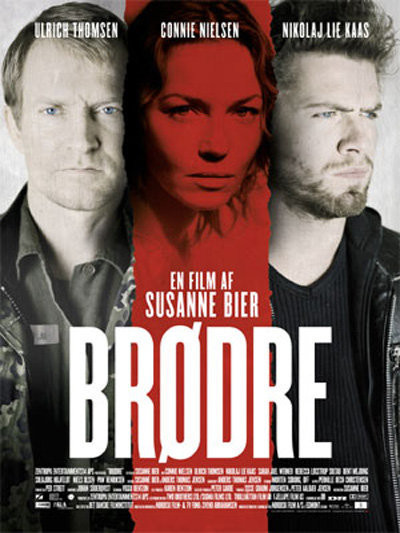

The central performance in “Brothers” is by Connie Nielsen, who is strong, deep and true. You may remember her from “Devil's Advocate” and “Gladiator.” What is she doing in a Danish movie? She is Danish, although this is her first Danish film.

The brothers are Ulrich Thomsen as Michael and Nikolaj Lie Kaas as Jannik. Both have to undergo fundamental transformations, and both must be grateful to Bier and Jensen for not getting all psychological on them. “Brothers” treats the situation as a real-life dilemma in which the characters behave according to how they are made and what they are capable of doing.

Like “Open Hearts,” this is the kind of movie that doesn’t solve everything at the end — that observes some situations are capable not of solution but only of accommodation. That’s more true to life than the countless movies with neat endings — happy endings, and even sad ones. In the world, sometimes the problem comes and stays forever, and the question with the hardest answer is, well, OK, how are you going to live with it?