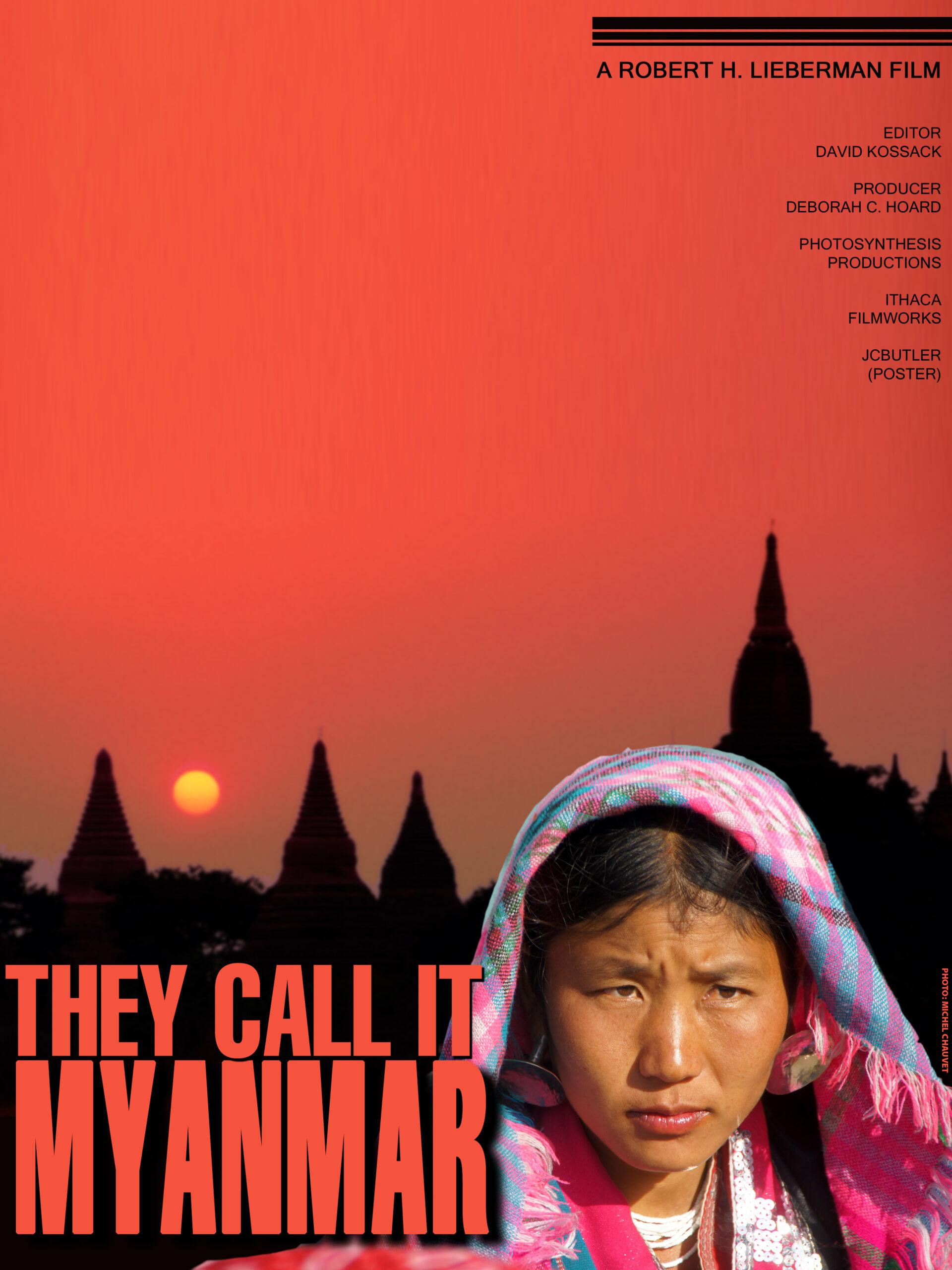

“They Call It Myanmar: Lifting the Curtain” is the much-discussed new documentary about the sealed-off nation of Burma. The film could also have been titled, “The British Renamed it Burma.” Under any name, it is a beautiful nation, sharing borders with Thailand, China, Bangladesh and India.

Here is a nation that has undergone much hardship after winning independence from Britain in 1948. It was controlled until 2011 by a military dictatorship. It is currently in the process of democratic elections, and on Sunday its famed Nobel Peace Prize winner, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, apparently won a seat in Parliament.

She is one of the subjects of “They Call It Myanmar,” a film that was shot secretly by Cornell professor Robert H. Lieberman during two visits there arranged by the U.S. Department of State. Held under house arrest for most of her adult life, Suu Kyi is the leader of the main opposition party. She is composed and serene, sounding not like an angry dissident but like a reasonable and balanced person. She embodies gentle intelligence. As it turns out, her 15 years of house arrest ended not long after this interview was filmed.

It is reckless to make broad generalizations about any group of people. I don’t want to imply that the Burmese under military rule are happy. What I do observe is a land where the precepts of Buddhism are so embedded that philosophical acceptance is widespread. It is not a successful nation. The national economy lags far behind its neighbors in southeast Asia, its educational level is unusually low, and although its tourist business thrives, the nation (at least as seen here) has not yet been colonized by fast food and chain stores that make much of the world look like a Western shopping mall. Even Lieberman, an outspoken critic of its military regime, loves it.

His film, made unofficially and on a shoestring, is nevertheless a thing of beauty; its cinematography, music and contemplative words make it not an angry documentary but more a hymn to a land that has grown out of the oldest cultures in Asia. With the new election news, the film has taken on an unexpected buzz, and the Landmark Theater chain has made it a special event. It’s showing twice in Chicago — at 7 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday (April 4 & 5) at Landmark’s Century Centre Cinema, with director Robert H. Lieberman in person on Wednesday. Screenings in the near future will be held in Landmark theaters in San Francisco, Seattle, Los Angeles and San Diego. Dates and showtimes are here: http://bit.ly/GWogIy

The movie lacks a tight agenda. Lieberman and others poke around here and there, asking people questions; voice-overs are anonymous and some of the on-camera interviews have the faces of the subjects blanked out. There is a devastating contrast between the rich and poor. At the wedding of a general’s daughter, she boasts of a necklace of real diamonds, and we see luxury resorts and consumer goods. But few of the masses receive more than one year of schooling, there are no child labor laws, and although we learn that the girl with the ulcerous hole in her chest is “treatable and curable,” that would cost $5. Medical care for most people is limited to “quacks” — that’s the actual local word — who may have picked up a little knowledge by sweeping the floors at a clinic and watching doctors at work.

Lieberman’s film is the only doc about Burma available. I gather he may not be an infallible source. He’s informed by a fellow foreign passenger that the buses leading up a steep hillside to a temple often plunge off the road, killing everyone on board. Douglas Long, in the Myanmar Times, writes: “The drivers, the man further explains to the camera, are not bothered by the prospect of dying. On the contrary, they consider it an honour to sacrifice their own lives while performing the meritorious deed of carrying pilgrims to one of the most sacred Buddhist sites in Myanmar.”

Long says in his nine years of working for the newspaper such an accident has never occurred, and “those who live in Myanmar will immediately recognise the man for what he is: a charlatan unable to resist the compulsion to impress others with ‘special knowledge’ about the supposed dangers of visiting ‘exotic’ locales like Myanmar.” I am reminded of the tall tales told by local guides in Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad.

Such footnotes aside, the importance of the film is simply to provide us images for the words Myanmar or Burma. Here is the second largest country in Southeast Asia, and most Americans know hardly anything about it. What I’ve come away with is a notion of a land which, despite its crushing problems, has produced a population that seems extraordinarily radiant.