It’s a great—and as yet untold—story: Jan Zabinski and Antonina Zabinska, Polish husband and wife zookeepers, owners of the Warsaw Zoo, opened their zoo to Jewish refugees after the September 1939 German invasion of Poland, and continued to “host” people throughout the occupation, smuggling them out of the Warsaw ghetto, hiding them in animal cages and basement tunnels leading from the house to the zoo. Considering that the German army had commandeered the zoo for an armory, this “hiding in plain sight” strategy was extremely risky. Diane Ackerman, an author who focuses on the natural world, told the tale in her book The Zookeeper’s Wife, dovetailing stories of animal camouflage techniques with stories of human survival. Sometimes the metaphor was a bit strained, but Antonina’s vivid journals (she also wrote a children’s book about animals) was the thread that held it all together. Only 2 of the 300 Jewish “guests” (as they referred to them) hidden in the zoo were captured by the Nazis and murdered. The rest survived.

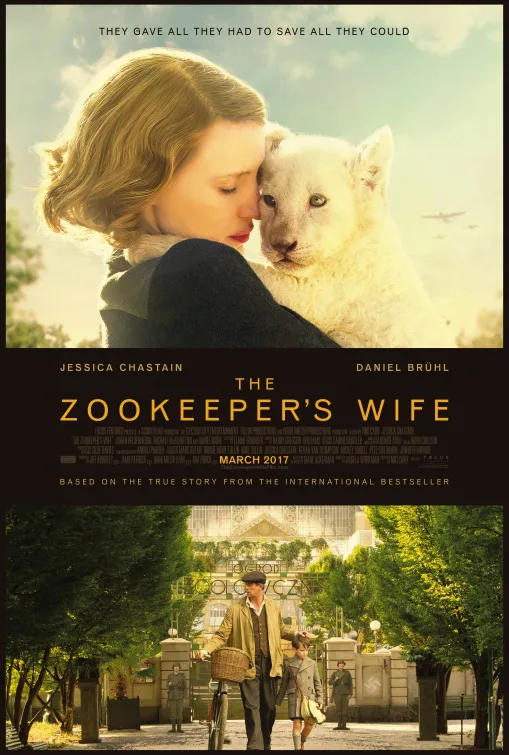

The film adaptation, written by Angela Workman and directed by Niki Caro (“Whale Rider“), has many lovely and moving moments but fails to capture the many layers of this unique story, relying instead on plainly-stated metaphors. “A human zoo,” Antonina (Jessica Chastain) breathes, when Jan (Johan Heldenbergh) suggests they take in Jews. There are also some fictionalizations that come straight out of the familiar and cliched Nazi-movie playbook. The opening sequences are effective, showing Antonina’s daily routine before the bombs start falling, her affinity for animals, her Snow-White-like gift for relating to them on their level. She is called to the elephant yard to aid with a suffocating baby elephant, and is able to remove the obstruction from the baby’s trunk all while calming down the panicked mother elephant. The couple’s villa, on the zoo premises, is filled with an eccentric menagerie: badgers and parrots and a pair of baby lynxes, snoring in bed with the Zabinski son Rys (the Polish word for lynx). It’s an Edenic world.

But so much information is missing, including the real personalities of these eccentric and tough people. Jan’s involvement in the Polish Underground and the Home Army, his weapons stashes all over the city, his long absences, are sketched in, if that. He is shown fighting the Germans at one point, but it’s handled so haphazardly it’s not clear what’s going on. In the book, Jan and Antonina carried cyanide pills on them at all times, to be used if their secret should be discovered. What an illuminating fact! But Workman chooses to leave that out (and many other details), focusing instead on the less-interesting (and fictionalized) domestic dramas going on inside the house: Antonina coaxing a feral Jewish child (raped by Nazi soldiers) to trust her, in the same way she coaxed animals to trust her, in case you didn’t get the connection. “The Zookeeper’s Wife” also spends a lot of time showing the lengths Antonina goes to to ingratiate herself to nosy German zookeeper Lutz Heck (Daniel Brühl). She flatters him, flirts with him, and all of this makes Jan jealous. There are unfortunate moments when the real cliffhanger of the film is whether or not Antonina will sleep with Heck, instead of what will happen to the Jews curled up in animal pens.

Caro is on sure ground when showing familiar events through a new filter. There’s a haunting sequence on the day of the invasion when the animals in the zoo sense what is coming before the humans do. The sound drops out. The tiger paces wildly in its cage. The monkeys scream into the air. When the zoo is bombed, the animals are let loose on the city, and Warsaw residents peek out their windows at the bizarre sight of a camel trotting by, or a couple of lions prowling through rubble on the corner. Caro shows some of the activities of the Polish Underground, its organization and coordination: setting up a room in the back of a bakery where documents are forged, the rituals of dyeing Jewish black hair platinum blonde, the underground-railroad of helpful citizens who put their lives on the line to save their neighbors, the machinations and bribes that allow Jan to enter the Ghetto officially, and smuggle people back out: these details are fresh, specific, frightening.

Meanwhile, back at the zoo, Antonina hangs out with Heck, listening to his babble about the Nazi’s plans to breed back to life the extinct “auroch” as a testament to German’s racial purity, and she unbuttons her top button, allows him to wash her hands near the bison pen. These sections are forced, unnecessary. The villain is not Lutz Heck the potential rapist-seducer Nazi. The villain is the Nazi war machine and the racist ideology that kept it alive.

Jessica Chastain is an actress who quivers with a vulnerability so palpable you can practically see the pulse beating in her throat. She is able to completely submerge her softness (“Crimson Peak“), or transform that softness into single-minded obsession (“Zero Dark Thirty“) or taut anxiety (“Miss Julie”). In “Take Shelter,” her wifely concern for her husband’s increasing madness is partially why Michael Shannon’s performance is so powerful. And of course there’s “The Tree of Life,” a celebration of her vulnerability. As Antonina, though, Chastain seems bound up as an actress, held back in creating a character mainly by the demands of doing a Polish accent.

If an actor’s accent is belabored and clumsy, the audience doesn’t think, “Wow, I am so involved in this story.” They think, “Oh, look, a famous actor trying to do an accent.” Chastain’s inconsistent Polish accent calls so much attention to itself that even she seems aware of it, lowering her voice to a near-whisper throughout. She is surrounded by European actors, all of whom speak English in a variety of accents (and Jan is played by a Flemish actor), so her attempt is even more distracting.

These are some pretty serious caveats, but it’s important to reiterate that there are many sequences of the film that work beautifully, filled with emotion and tension, fear and pain (the Warsaw Ghetto scenes are especially terrible, a spectacle of horror). The story of the zookeepers who risked their lives repeatedly throughout the war is an incredibly moving and important story, in and of itself. Years later, when asked why they did what they did, Jan Zabinski answered, “I only did my duty—if you can save somebody’s life, it’s your duty to try.”