Terry Gilliam, the onetime Monty Python animator turned influential filmmaker, is incapable of putting a dull image onscreen. “The Zero Theorem,” his first science fiction movie since 1996’s “Twelve Monkeys,” is a visual dazzler on the level we’d expect from the director. As always, he fills the screen with intricately choreographed tableaus that have that ferociously jumbled quality: there are usually four or five things going on in each shot, and they’re always related to the film’s main themes. The cast, which includes Christoph Waltz, Melanie Theirry, Matt Damon and David Thewlis, is world-class. It’s hard to imagine how any individual part of the physical production could be improved.

But the movie’s allegory-steeped plot — in which Waltz’s, Qohen Leth, who “crunches entities” for a technology company called Mancom, tries to solve a theorem that’ll reveal if life has meaning — is a case of “close, but no cigar.” And no matter how feverishly Gilliam directs and no matter how enthusiastically his actors act, the whole thing remains too, er, theoretical—as if its main purpose is to demonstrate or disprove certain propositions rather than invest us in the hero’s quest for happiness and enlightenment. Knowing Gilliam’s humanism, this seems unlikely, but that’s what comes through.

Screenwriter Richard Pushin was reportedly inspired by the book of Ecclesiastes, but the plot seems equally influenced by “Waiting for Godot,” “1984” and the collected works of Franz Kafka (the latter two sources shaped Gilliam’s “Brazil” as well). Even though it was written directly for the screen, “Zero Theorem” often feels like a stage play that was adapted without being fully remained as a movie. It’s visually energetic but ultimately feels constrained and repetitious. The main locations are Mancom headquarters, a nightclub filled with writhing revelers, and the hero’s apartment/laboratory, a cavernous space with a black-and-white chessboard-style floor and smoky shafts of light streaming through windows. The cathedral-like quality of Quohen’s place befits the spiritual pilgrim who occupies it. Quohen has been depressed and angry for a long time because he keeps hoping for a phone call that will assure him that life has meaning (shades of “Godot”) ; when it finally arrives, he muffs it and spends the rest of the movie beating himself up.

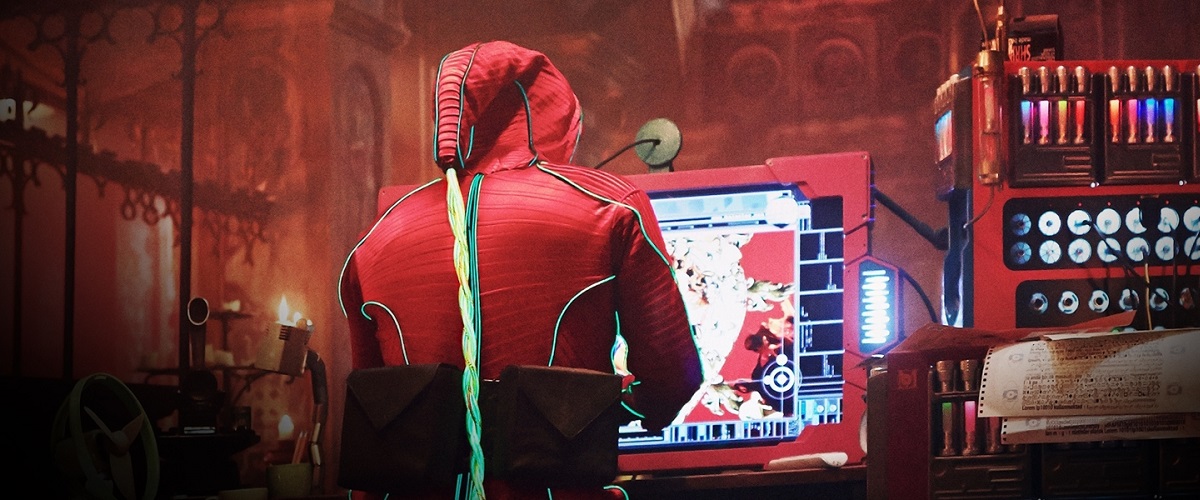

Quohen is reassigned to work at home by the company’s psych evaluator, Dr Shrink-Rom (Tilda Swinton), an artificially intelligent computer program who simulates warmth and involvement. (Swinton is hilariously intense here; between this role and her bucktoothed-Ayn-Rand routine in “Snowpiercer,” the Hugos should give her a Most Valuable Player award.) Quohen gets diagnosed with ailment after ailment and eventually dons a body suit that connects him directly to the Internet, making his physical being virtual. It’s red and green, with a hoodie cap like a droopy Alpine horn that tapers into braided, vaguely intestinal cables. When Quohen wears the suit while sitting at his terminal typing, the image suggests a porn-addicted Christmas elf.

Other characters drift in and out of the story, alleviating or increasing the hero’s irritability and spiritual malaise. The curvy blond Bainsley (Mélanie Thierry) rescues Quohen at a party when he nearly chokes on an olive, and proves responsible for getting him reassigned to work at home, then keeps reappearing in his life, eventually providing him with his signature elf suit and then being revealed as a secret Internet striptease artist. Many of the characters evoke indelible players from Gilliam’s “Brazil”: there’s a Walter Mitty or Winston Smith-type wise-yet-meek everyman (the hero), an obnoxious mediocrity of a supervisor (David Thewlis), and a blandly intimidating boss (Matt Damon), whose character is identified only as Management, and whose natty suits, owlish eyeglasses, grey hair and dulcet voice make him seem like Peter Bogdanovich’s all-powerful kid brother.

There are some twists and turns in the plot, all having to do with the true meaning and purpose of the Zero Theorem. At the end, the mysteries are laid out for us methodically, as if we’re seeing the philosophical version of a drawing-room mystery where the murderer is the Frankensteinian post-capitalist society we’ve all gotten way too comfortable with, and the victim is the human soul.

I wish, however, that the characters were allowed to be as well as to represent, if that makes sense. Gilliam’s other films, even the bad ones, all managed to balance the need to deliver aphorisms and lessons against the obligation to involve us in the characters’ plights. Every character in this movie remains stubbornly and elusively abstract. We know what everybody stands for, but we never really know them. After a while you start to miss the aching humanity of Sam Lowry in “Brazil” or the lovers in “Twelve Monkeys,” or the exquisitely fragile energy of Robin Williams in Gilliam’s “The Fisher King.”

The movie’s at its most engaging when it’s just showing us the world that causes Quohen such distress. An early scene in which the hero leaves his abode and tries to walk along a city thoroughfare while a video ticker on the side of a building tracks him with tailored sales pitch is a marvelous comment on how technology turns every environment into a retail outlet, and every person into a target of opportunity. (It’s like that moment in “Minority Report” where Tom Cruise walks through a mall while ads chirp at him.) There are some exquisitely blocked and executed long takes, and a virtual-fantastical interlude on a tropical beach that ranks with the best scenes Gilliam has directed. In its better moments, “Zero Theorem” does seem like the work of a brilliantly cranky cartoonist who’s spent years obsessing over what the world has become, then finally sat down, opened a sketchbook and started drawing. The problem is, once you’ve watched “Zero Theorem,” you’d rather go look at the sketchbook.