The action in “The Yellow Handkerchief” takes place within the characters, who don’t much talk about it, so the faces of the actors replace dialogue. That’s more interesting than movies that lay it all out. This is the story of three insecure drifters who improbably find themselves sharing a big convertible and driving to New Orleans not long after Hurricane Katrina.

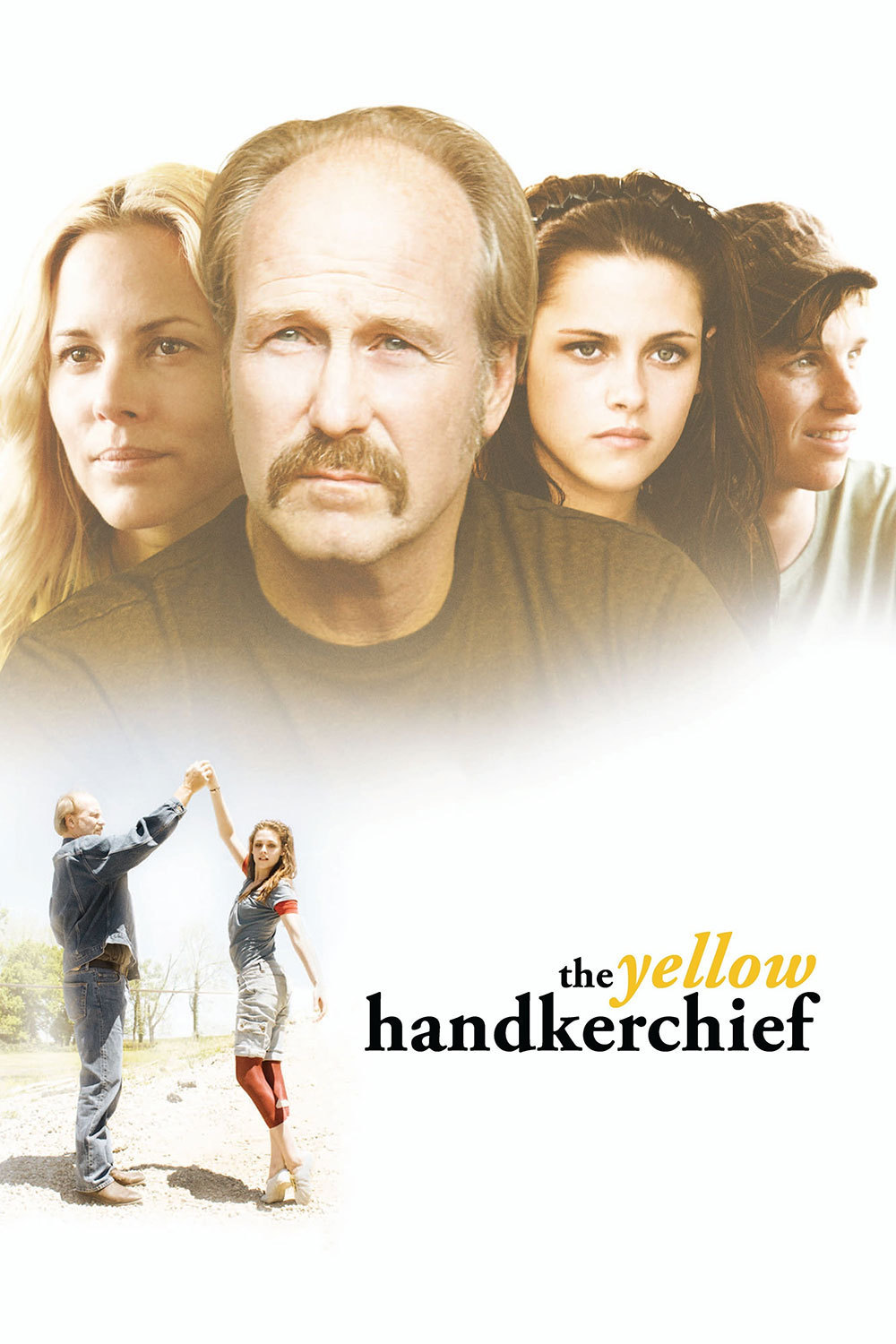

The car’s driver is a painfully insecure teenager named Gordy (Eddie Redmayne), who doubts most of what he does and seems to apologize just by standing there. At a rural convenience store, he encounters Martine (Kristen Stewart), running away from her life. He says he’s driving to New Orleans. No reason. She decides to come along. No reason. They meet a quiet, reserved man named Brett (William Hurt), and she thinks he should come along. No particular reason.

We now have the makings of a classic road picture. Three outsiders, a fabled destination, Louisiana back roads and a big old convertible. It must be old because modern cars have no style; three strangers can’t go On the Road in a Corolla. It must be a convertible because it makes it easier to light and see the characters and the landscape they pass through. They must be back roads because what kind of a movie is it when they drive at a steady 70 on the interstate?

The formula is obvious, but the story, curiously, turns out to be based on fact. It began as journalism by Pete Hamill, published in the early 1970s. In the movie’s rendition, Brett fell in love with a woman named May (Maria Bello), then spent six years in prison for manslaughter charges, although his guilt is left in doubt. Martine slowly coaxes his story out of the secretive man.

You don’t need an original story for a movie. You need original characters and living dialogue. “The Yellow Handkerchief,” written by Erin Dignam, directed by Udayan Prasad, has those, and evocative performances. William Hurt occupies the silent center of the film. In many movies we interpret his reticence as masking intelligence. Here we realize it’s a blank slate, and could be masking anything. Although his situation is an open temptation for an actor to signal his emotions, Hurt knows that the best movie emotions are intuited by the audience, not read from emotional billboards.

Stewart is, quite simply, a wonderful actress. I must not hold the “Twilight” movies against her. She played the idiotic fall-girl written for her, as well as that silly girl could be played, and now that “Twilight: New Moon” has passed the $300 million mark, she has her choice of screenplays for her next three films, as long as one of them is “The Twilight Saga: Eclipse.” In recent film after film, she shows a sure hand and an intrinsic power. I last saw her in “Welcome to the Rileys,” where she played a runaway working as a hooker in New Orleans. In both films she had many scenes with experienced older actors (Hurt, James Gandolfini). In both she was rock solid. Playing insecure and neurotic, yes, but rock solid.

The story of Redmayne, who plays Gordy, is unexpected. He fits effortlessly into the role of the scrawny, uncertain 15-year-old Louisiana kid. Yet I learn he is 27, a Brit who went to Eton, a veteran of Shakespeare and Edward Albee. Michael Caine explained to me long ago why it’s easier for British actors to do American accents than the other way around. Whatever. You can’t find a crack in his performance here.

These three embark on a road odyssey that feels like it takes longer than it might in real life. Their secrets are very slowly confided. They go through emotional relationships expected and not expected. They learn lessons about themselves, which is required in such films, but are so slowly and convincingly arrived at here that we forgive them. There is rarely a film where the characters are exactly the same at the end as they were at the beginning. (Note: Being triumphant is not a character change.)

Prasad made a wonderful British film in 1997, “My Son the Fanatic.” I’ve seen none of his work since. Now comes this redneck slice of life. Since the characters are so far from the lives of the actors and the director, this is a creation of the imagination. As it must be. The ending is a shade melodramatic, but what the heck. In for one yellow handkerchief, in for a hundred.