“My Son the Fanatic” tells the story of a taxi driver of Pakistani origins, who for many years has lived in the British midlands. He works at night to make better money, and finds himself giving rides to hookers and their clients–and sometimes helping them to meet one another. There is one hooker he rather likes, because she sees him as an individual, something few other people in his life seem able to do.

The driver, whose name is Parvez, is played by Om Puri, an actor of great humor and wisdom, whose weathered face can be tough and sad. He shares an uneventful marriage with his wife, Minoo (Gopi Desai), who regards him with mute but unending disapproval. Their lives are briefly brightened when their son Farid (Akbar Kurtha) is engaged to the daughter of the local police inspector, but then Farid breaks it off (“Couldn’t you see how they looked at you?” he asks his father, after a visit to the girl’s parents). The son turns to fundamentalism, and is soon listening to religious tapes, wearing a costume to set himself apart from others, and asking to move a visiting guru into Parvez’s home.

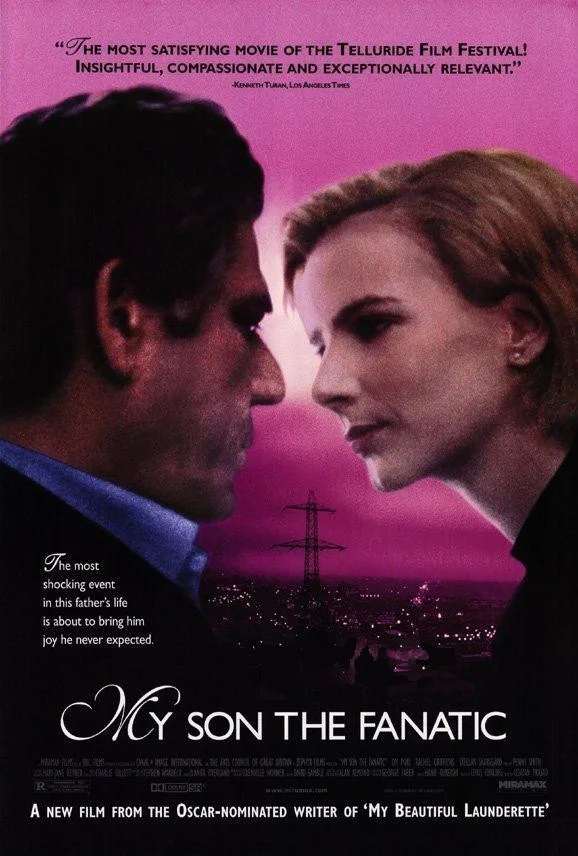

Real life for Parvez takes place in his cab, and we meet Bettina (Rachel Griffiths), the tough, realistic hooker he has a soft spot for. He recommends her to a visiting German businessman (Stellan Skarsgard), who has low tastes and a lot of money and treats Bettina in ways that make Parvez wince. Parvez spends long hours at work, and at home has carved out a little space in the basement that he can call his own–playing jazz records, drinking Scotch, listening to the voices upstairs of the guru and his followers, discussing their “mad ideas.” There is of course racial discrimination in England (I sometimes wonder if North America, for all our faults, is not the most successful multiracial society on earth). There’s an ugly scene in a nightclub, where Parvez has taken Bettina and the German, and is singled out after a comic shines a spotlight on him. And another scene, ugly in a quieter way, when Parvez takes Bettina to the big restaurant operated by his old friend Fizzy, who emigrated from Pakistan with him. Fizzy does not approve of Parvez bringing any woman not his wife (and especially not this woman) into the restaurant, and officiously sets a table for them in an empty storeroom.

The film was written by Hanif Kureishi, the novelist whose screen credits include “My Beautiful Laundrette.” His stories often involve children in rebellion against the values of their parents, but here he turns the tables: It is Parvez who lives like a teenager, staying out late and cherishing his favorite albums in the basement, and his son who occupies the upstairs and preaches conservatism and religion. Parvez is not a rebel, just a realist who asks himself, “Is this it for me? To sit behind the wheel of a cab for the rest of my life and never a sexual touch?” When Bettina kisses him, says she can’t remember the last time she kissed a man, and quietly reveals that her real name is Sandra, we believe them as a couple, however unlikely: In a lonely and cold world, they see each other’s need.

Om Puri’s performance is based on the substantial strength of his physical presence, and on his clear-sighted view of his world as an exile. When the guru comes to Parvez with requests that the son would be shocked to hear, he is not surprised: “You are so patriotic about Pakistan,” he tells the guru. “That is always a sign of imminent departure.” He instinctively suspects any religion, even his own, when it operates as a tribe: He is tolerant in his very bones, and dislikes religions that use costumes, fear and peer pressure to set their members aside from the mainstream. In accepting the hooker, he accepts all outcasts and pariahs, judging them on their character rather than their affiliations.

The movie contains a lot of humor, much of it generated by the creative differences between standard English and its variations in India and Pakistan. Parvez has a knack for putting a slight satirical spin on a phrase by not quite getting it right. When the police inspector is late to their meeting, he observes, “The law never sleeps at night!” When a man smokes in his taxi: “Please, sir! No smoking indoor! Smell is deafening.” There is humor, too, in his concern about his son’s strange behavior. At first, he suspects drugs rather than religion, and asks Bettina to write him out a list of the danger signals of addiction. When he tries the questions out on his son, the boy groans, “I can always tell when you have been reading Daily Express.” The film’s director, Udayan Prasad, knows, as Kureishi does, that there are no simple solutions to the dilemmas of their story. For that reason, it is more than usually important to sit through the closing credits (and even to request the theater management to be sure not to turn up the lights prematurely). The credits roll over a long shot that is not just a closing decoration, but really the resolution of the whole story, such as it is. In a way we are all exiles. In a way there is never going to be any home.