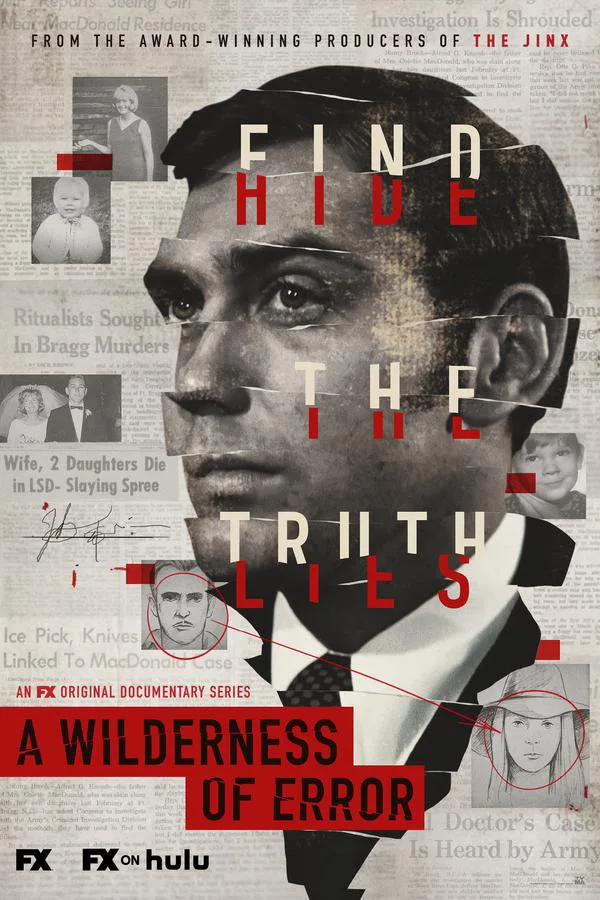

When Errol Morris released his book A Wilderness of Error in 2012, I grabbed it because I love Morris as a filmmaker, but I was surprised he was tackling the story of Jeffrey Macdonald because, well, I didn’t think there was much story to tackle. As Morris elucidates in the book and new mini-series based on it that premieres on FX this week, the narrative that grabbed hold in the public conscious about the case, pushed by a high profile NBC mini-series called “Fatal Vision,” clouded the truth. And yet the version of the truth pushed by that series and the prosecution could still be right. What’s remarkable about the Macdonald case, and what elevates “A Wilderness of Error,” is how no one theory seems to fit all the evidence. Nothing quite adds up, which makes the competing narratives about what happened that fateful night all the more intriguing. For some people, this is not an unsolved mystery. For others, it’s a wild miscarriage of justice. However, what’s most fascinating is how much Morris, a major part of the docuseries, is willing to exist in the space in between, uncertain if Macdonald is guilty or innocent. We don’t like uncertainty. We like to walk away sure of what happened. I’m increasingly convinced we will never have that clear-cut feeling about the Macdonald case, which makes it one of the most intriguing of the twentieth century.

Army Surgeon Jeffrey Macdonald lived with his wife Collette and two young children (Kimberley and Kristen) at Fort Bragg, North Carolina in February 1970 when military police were called to his house and discovered a scene of unimaginable horror. Collette was on the bedroom floor, covered in blood, with Jeffrey beside her. At first, they thought he was dead too until he started to move, and then they went to check on the children, both of whom had been stabbed to death in their own beds. Weapons were found outside the house, including an ice pick and knife, and the word “PIG” had been scrawled in blood on the wall.

Macdonald’s story was a terrifying vision of something akin to the Manson Murders, which had happened less than a year earlier. He said that three men and a girl in a floppy hat broke into the house and started attacking Macdonald and his wife, chanting things like “Acid is groovy, kill the pigs.” He fought them off, but was knocked unconscious, and he woke to find the horrible scene. He tried to do CPR on his wife and called the police.

From the beginning, the authorities found Macdonald’s account suspect. The physical evidence, including a lack of injuries to Macdonald himself and inconsistencies in his story, never seemed to quite fit his version of events. One particular fact that always stuck with me was that there was no fingerprint in the blood writing on the wall because a surgical glove, of the kind Macdonald the surgeon had in supply, was used—it seems like a premeditated murderer trying to stage a scene would be far more likely to wear a glove than a thrill-killing hippy. There was simply very little evidence that four other people had been in the house, and the Army started a detailed investigation, leading to an Article 32 hearing, at which, well, Macdonald’s story started to make more sense.

It all comes down to a woman named Helena Stoeckley, or potentially the “girl in the floppy hat,” someone that an officer that night claimed to have seen near the scene, and someone who confessed over and over again over subsequent years to having been there that night. Despite Stoeckley’s confessions and the Article 32 hearing, the justice department went after Macdonald, convicting him of multiple murders in 1979. He’s still behind bars, professing his innocence.

There’s clearly enough room for reasonable doubt in this case, which is likely what attracted Errol Morris to it, and it’s fascinating to hear him openly admit that he was hoping for something similar to happen with The Wilderness of Error to what happened with “The Thin Blue Line,” his brilliant documentary that led to the release of an innocent man. But what’s even more interesting is that Morris himself would agree that this case isn’t nearly as cut and dry as that one. Over the five episodes of “A Wilderness of Error,” you will go back and forth on Macdonald’s guilt. Why did he say that he stopped CPR on his wife because of a chest wound she didn’t actually have? Why was he so relatively unharmed? Why did murdering hippies not bring their own weapons and use a glove? And the blood trail evidence doesn’t fit his story. On the other hand, why did Stoeckley confess so many times? Why did another man suspected of being there, confess in writing on a wall? Why did people in the area claim to have seen Stoeckley in the floppy hat that night?

None of it makes sense, which makes for great documentary television, and this Blumhouse production is polished and refined. We are always fascinated by the cases that will never be completely solved—Jack the Ripper, The Zodiac Killer, JonBenet Ramsey. And director Marc Smerling, working closely with Morris as an interview subject in the FX series, captures the swirl of narratives in this particular case with tight editing and expert construction. Smerling produced “Capturing the Friedmans” and “The Jinx,” so he knows how to take these complex stories and make them engaging and easy to follow. And yet he’s also willing, like Morris, to get lost in them, as confused as we are about the truth. This is smart, challenging docuseries filmmaking that maybe could have benefitted from being one episode shorter, but it doesn’t drag nearly as much as some other 2020 true crime series. Smerling and Morris are great partners here, and I loved just watching Morris wrestle with his own role in this story now in the final chapter, as he helped lead an appeal attempt in 2012.

“A Wilderness of Error” is a reminder that when so many competing stories start to fight for the same space, the truth gets further and further away instead of closer. And it feels like the truth of what happened that night a half-century ago is more lost in the wilderness than ever before.