“The Whistle Blower” is about the British spy establishment, but at first it doesn’t feel at all like a spy movie. It begins as the quiet account of the daily life of a middle-age man who has set up in the office equipment business and who almost welcomes his anonymity. He once was in intelligence, he once was at the center of important matters, but now he has put all that behind him.

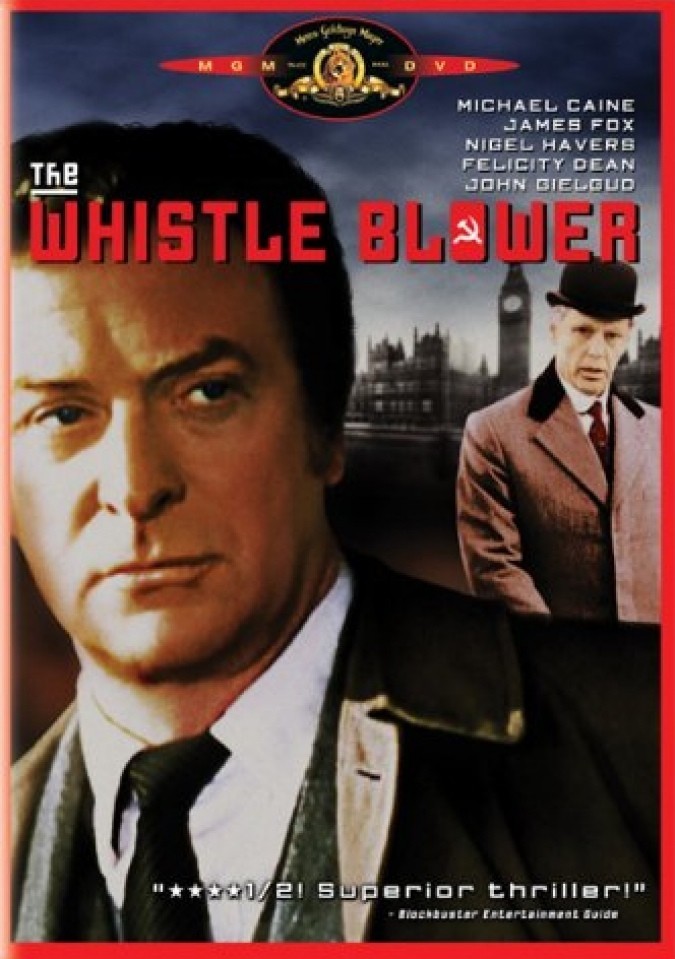

The man is played by Michael Caine, with a quiet self-effacement that is very convincing. He is mild and soft-spoken, and it is clear that to some extent he is living his life through the life of his son, whom he loves very much. The son is a likable, disorganized, untidy, very serious young man who is in love with an older woman with children.

Caine is not sure this is the right relationship, but in his performance there are a few quiet, crucial moments when he seems to do nothing – he just sort of stands there in a shot, regarding those around him – and you can feel his hope that his son will be happy.

Caine is such a good actor that he doesn’t overplay those moments, or indeed seem to play them at all. Yet they underlie the whole film. We begin by understanding that Caine has placed action behind him, we identify with his new emotional calm, we sense his love for his son and that prepares us for everything that follows.

It is important that I not reveal, however, too much of what follows. “The Whistle Blower” is not a conventional spy thriller, but it does depend upon surprises and unexpected revelations of character, and they grow naturally out of the story. In general terms, I can say that Caine’s son becomes a pawn in an intelligence game with much higher stakes and that what Caine eventually comes to understand is that little people such as him and his son are expendable in the view of the entrenched establishment that rules the country.

Like another recent British thriller, “Defense Of The Realm,” this movie uses the British spy apparatus as a way of dramatizing the class distinctions that still exist in Britain. The Caine character is in reaction against the feeling that nothing – not God, not the throne, not patriotism, certainly not security considerations – is as important as defending a network of privilege. The crucial moment in the film comes when Caine accuses a traitor of letting innocent people die, just so that he can continue to have tea with the queen. The steps by which Caine arrives at this speech are what the movie is about.

“The Whistle Blower” hardly is ahead of the headlines in Britian right now. The Spycatcher controversy has the country in an uproar against the action of five bewigged Law Lords, solemnly forbidding the press from printing details from a book that is a worldwide best seller. The book alleges, of course, that a head of British intelligence was a Soviet mole from the start, the same assumption “The Whistle Blower” is founded on.

Despite a few obligatory scenes of threat and violence, most of the action in the movie takes place within the mind of the Caine character. Caine turns in three quite different performances in “The Whistle Blower,” as the slimy Soho mob boss in “Mona Lisa” and as the maverick spy who tries to prevent a nuclear explosion in “The Fourth Protocol,” which is scheduled to open Aug. 28. The three performances are completely different, and yet it is hard to see what Caine does differently in them. He has the same dry, flat inflection, the sometimes masked face, the way of seeming to stand completely impassively until action is called for, the sense of enormous reserves of strength and anger banked inside.

Yet in “Mona Lisa” he is a villain, in this film he is a decent, angry man, and in “The Fourth Protocol” he is more of an action hero.

It all seems to come from inside. The one thing you will rarely catch Caine doing in a movie is seeming to go for an effect. Maybe that’s why he achieves them so consistently; the screen is a magnifying glass that rarely forgives excess.

What’s especially nice about “The Whistle Blower” is that it never quite lets plot become more important than character. Like a novel by Graham Greene, it isn’t really about what happens, but about how the events feel to the characters and how they change them.

I can’t remember ever having seen Michael Caine play a father, but there is a scene in this movie, a quiet walk and talk between father and son, that is as touching a portrait of parenthood as I can remember.