“The whole world is watching!” This iconic chant from the protest movement of the ‘60s is featured multiple times in Aaron Sorkin’s “The Trial of the Chicago 7.” The timing of the film’s release as laws against protest movements in the United States gain traction and one of the most important elections in the country’s history looms on the horizon is not a coincidence. Sorkin and Netflix, where the film will premiere on October 16th after a three-week limited theatrical run starting today, understand the timeliness of their project. It is meant to spark conversation about how far we’ve come since the riots of 1968 and subsequent trial in Chicago of the men accused of conspiring to provoke violence in the streets. And it is an accomplished ensemble piece, thick with great performances pushing for space in the same frame. The weight of the subject matter combined with the intensity of the acting here will be more than enough for some people, and I expect a few awards-giving bodies, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that it all felt a little too refined and manufactured. That Sorkin sense that everyone knows exactly what to say and do in any given situation, even as they express doubt with perfect diction and vocabulary, fits perfectly for a story like the invention of Facebook in “The Social Network” or even the birth of Apple in “Steve Jobs,” but the protest movement and the government’s attempt to quell it should be more organic than this film ever even flirts with being. It looks and sounds great, but should it?

Sorkin wastes no time throwing viewers into the chaos of 1968, introducing viewers to the key players in what would become known as the trial of the Chicago 7 as they plan their trip to the Windy City to protest the Vietnam War during the Democratic National Convention. Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) and Rennie Davis (Alex Sharp) encourage peaceful protests with an emphasis on the young lives being lost in an unjust war. Yippies Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong) have a more chaotic approach to protest, arguing that dismantling the system only happens when it’s disrupted first. David Dellinger (John Carroll Lynch) is a family man who assures his wife and son that nothing dangerous will happen in Chicago, as Bobby Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) promises he too will be in and out without much fanfare.

Of course, everyone knows what happened in Chicago in 1968—chaos erupted multiple times, leading to riots that caught international attention. Sorkin starts his film months later, with an angry Attorney General John Mitchell (John Doman) tasking Richard Schultz (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and Thomas Foran (J.C. MacKenzie) with the case of their lives, trying the men he believes were responsible for the unrest. The power has shifted from LBJ and AG Ramsey Clark (Michael Keaton) to Nixon and Mitchell, and they want to use Hoffman, Hayden, and the rest as examples of what will happen to those who protest the war. Mark Rylance plays the main attorney for the seven, William Kunstler, and Frank Langella is phenomenal as Judge Julius Hoffman, a man who teeters on that dangerous edge between incompetent and evil.

Clearly, this is a powerhouse cast, and they all relish the opportunity to chew on Sorkin’s timely and provocative language. There’s really not a weak link in terms of performance, and several of them shine in unexpected ways. Strong finds a winning vulnerability in Jerry Rubin; Rylance nails Kunstler’s increasing exasperation at a broken system; Mateen II’s simmering rage at even being dragged through the process is palpable; Redmayne finds the right key for Hayden’s righteous intellectualism; Keaton is perfect in only two scenes. There are such wonderful individual moments and beats in “The Trial of the Chicago 7” that just watching it as an acting exercise makes it worthwhile.

It’s when one considers the overall picture that things get a little hazy. The problems stem from Sorkin the director, not Sorkin the writer. Perhaps because of the importance he places on a script he’s been developing over a decade and has even more weight with the increased protest movement in 2020, Sorkin gets too precious with his characters and dialogue. It’s too polished—there’s no dirt under any fingernails, even Jerry and Abbie’s. Even a place that self-identifies as the Conspiracy House feels like a perfectly-lit set. These men were facing actual prison time and they very clearly understood their role in history, protest, and even public opinion of the Vietnam War, all during such a messy and uncertain era. But the stakes feel minimized here for that sheen Sorkin does so well, and it doesn’t have the emotional impact it should. A different director might have allowed the story to breathe outside of the razor-sharp dialogue and might have reined Sorkin in on some of the overwrought theatrics of the final act.

Still, there’s much to admire in individual beats of “The Trial of the Chicago 7.” I never would’ve guessed how much I would enjoy a hippie buddy comedy starring Sacha Baron Cohen and Jeremy Strong. Mark Rylance proves again why he’s one of our best—he’s the standout of the ensemble when it comes to making Sorkin’s dialogue sound like it’s actually being thought of just before it’s spoken. Frank Langella perfectly captures how dangerous it can be when incompetent men hold an amount of power that they’re incapable of really comprehending (read into 2020 politics what you will). All of these elements and more make “The Trial of the Chicago 7” into an engaging drama, but one that could have been as impactful as that unforgettable chant if it was more willing to embrace imperfection. The whole world may be watching, but what are they going to feel when they do?

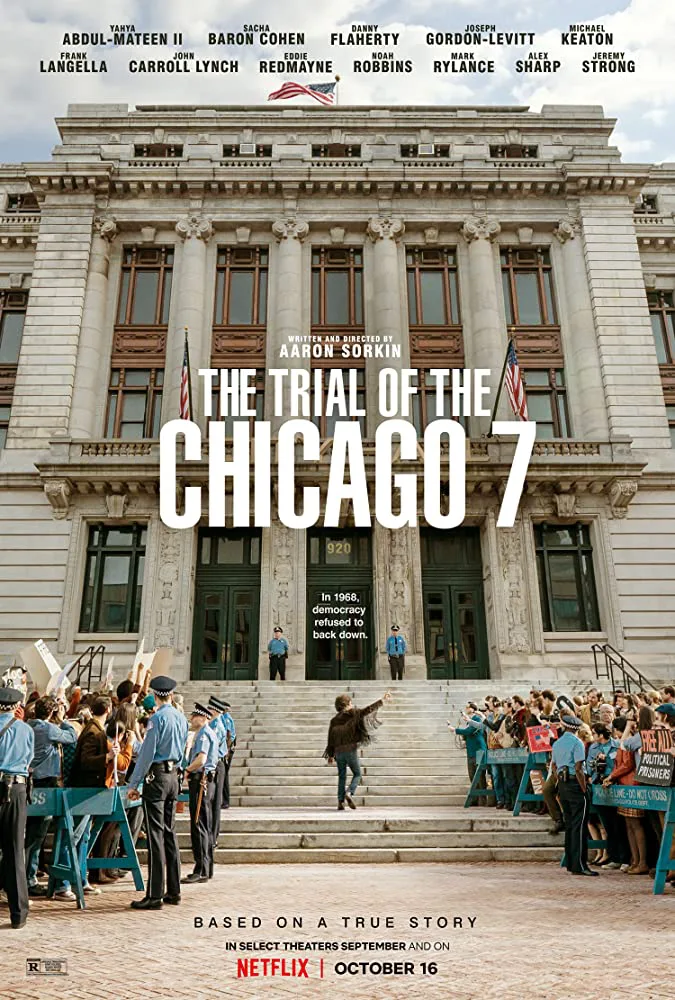

Now playing in select theaters; available on Netflix on October 16.