Burt Kennedy’s “The Train Robbers” is a very curious Western, and it gets curiouser the more you think about it. I wonder if there’s ever been a Western as visually uncluttered as this one. Most of the action takes place in the high desert around Durango, Mexico, and Kennedy goes for clean blue skies, sculpted white sand dunes and human figures arranged against the landscape in compositions so tasteful we’re reminded of samurai dramas.

Aw, come on, you’re probably thinking by now: What’s all this crap about visual compositions? It’s a John Wayne Western, isn’t it? Is it any good, or not? Well, yes, it’s fairly good, In a quiet and workmanlike sort of way, although there’s a plot twist at the end that ruins things unnecessarily. But what’s best about it, what makes it worth seeing, is Kennedy’s visual approach to the subject of John Wayne. Wayne by now is an artifact, a national heirloom, one of the few immutable presences created by the movies. He is perhaps the only Western actor alive (maybe the only one ever) who can get away with scenes like this one: His group has been riding through the desert all day, pursued by a mysterious band of gunmen. They pull up at a small hacienda. Will they spend the night there? No, because Wayne hears a baby crying. There is likely to be shooting later on, and Wayne asks Ben Johnson: “Did you ever bury a baby? Well, neither did I, and I’m not about to start now. Ride on.” They ride on into the night. Now this is honorable dialog; we agree with him; we’re glad Wayne doesn’t want to endanger the baby. And because it is John Wayne playing this scene, we never pause to realize that such a scene, and such dialog, would be ridiculously impossible in any other context. The audience would be howling if Steve McQueen or Paul Newman – or Robert Mitchum – tried the dialog.

Only Wayne can make plausible the morality in his Westerns. In the new Westerns, the ones by Sam Peckinpah, Sergio Leone and their imitators, the West is a place of anarchy, sadism and routine bloodshed. It almost has to be. Apart from Wayne, there are no actors left who can get away with being decent Western heroes. Am I making this up? Think for a moment.

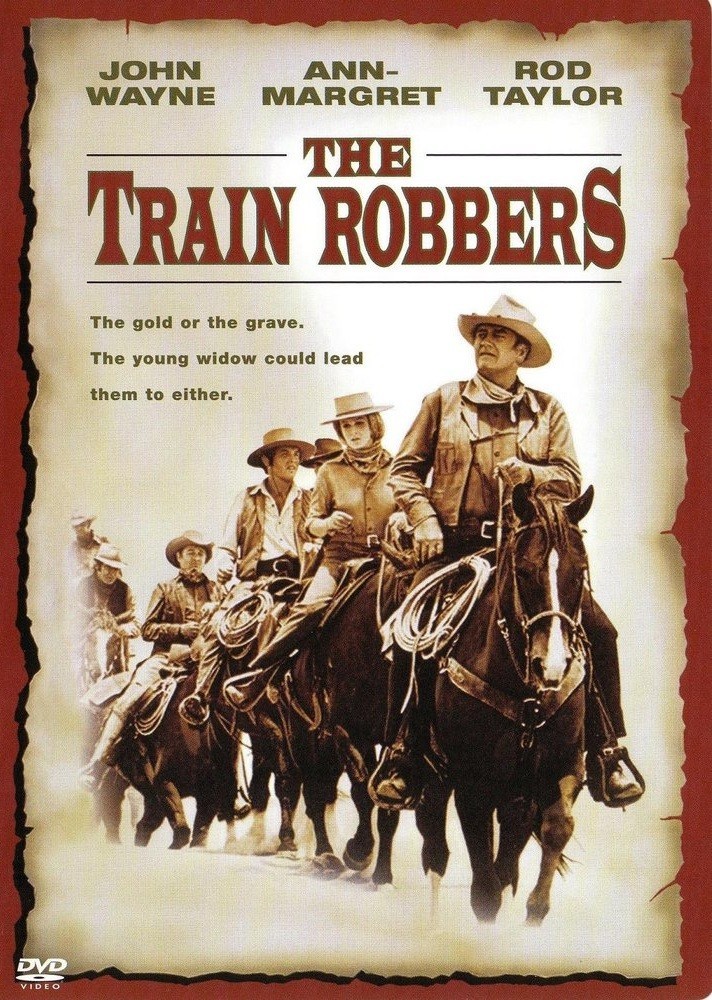

So. The Wayne character in “The Train Robbers” agrees to help a widow (Ann-Margret) recover some gold her husband had stolen some years before. She wants to return the gold to the railroad it was stolen from, to clear her husband’s name and allow her young son to grow up proud. This seems like a sensible plan to Wayne, and he raises a band of friends (Ben Johnson, Rod Taylor, and two younger guns) to help the widow. Their payment will be the $50,000 reward money – although at the movie’s end, they forgo even this.

There is a lot of action in the movie – blazing gun battles and stuff like that – but the movie’s core is in the campfire scenes, when the characters talk about each other and their beliefs. The Wayne character, not to our surprise, turns out to be heroic in war and noble in peacetime, a subscriber to old moral codes. And it is here that Burt Kennedy’s visual strategy comes in.

His material (he also wrote the movie) is, in the context of a Western being released in 1973, a little old-fashioned. The moral drives of Western heroes were fashionable in the 1950s, especially in the movies where John Ford directed Wayne. But no longer. In 1973, any plot exposition at all in a Western seems to drag.

So Kennedy wisely decided to eliminate absolutely every trace of visual clutter, and to shoot his movie with almost abstract clarity. The “town” at the beginning of the movie, for example, consists of two stark structures, a railroad track and a mountain on the horizon. There is not even a railroad crossing sign. Once out of town, the characters inhabit a landscape of horizons and clean natural lines. Kennedy goes for silhouettes and, as I’ve mentioned, for the kind of carefully casual arrangements of figures we find in samurai films – the Japanese Western.

The result is a movie that isolates the John Wayne mystique and surrounds it with the necessary simplicity and directness. It’s too bad that the scale of the plot is a little too small for the scale of the characters, and too bad that Kennedy got in an ironic mood at the end. But he understands John Wayne, all right.