The ads for “The Sterile Cuckoo” remind us that you can fall in love for the first time only once in your life. True enough, but that begs the question of whether Pookie and Jerry are really in love. I doubt it. Their relationship is based more on need: her need to be loved, and his need to make love.

When they’re able to fulfill their needs simultaneously, they convince themselves they’re in love. But making love is not the same thing as giving love, and the movie is about how they gradually figure that out. It shouldn’t take them as long as it does, but Pookie is so neurotically dependent that she hangs on much too long. And Jerry is slow. Stupid might be a better word.

Both characters are presented as freshmen in college, having their first love affair. They’re awfully normal kids, at least in exterior ways. They go to aggressively typical colleges in upstate New York, where the biggest thing on campus is a fraternity beer party. They wear college sweatshirts and their hair short. When it comes time for them to consummate their affair, they do what any 1927 Scott Fitzgerald hero would do: Go to a crummy motel and rent a room. They aren’t of the current generation, but they’re not really apart from it. I suppose there are more Pookies and Jerrys in the freshman class, even today, than sexually and politically sophisticated types.

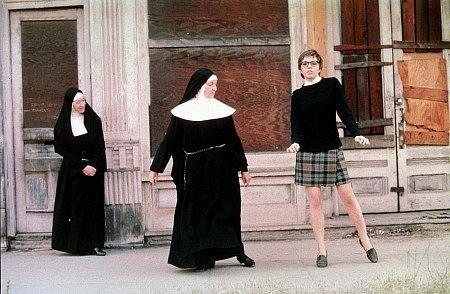

Director Alan J. Pakula has chosen, deliberately I suppose, to isolate his kids from any 1969 concerns and show them completely in terms of each other. For maybe 80 per cent of the movie they’re the only ones on screen. Liza Minnelli plays Pookie as an appealing eccentric who gradually cracks up as her hang-ups surface. Pookie is basically interested only in herself — boringly so, at times. But at least she cares enough to make an effort to reach someone else.

Jerry (played by Wendell Burton) doesn’t even care that much. He’s the kind of kid who stays on campus over Easter vacation, claiming he has to study — and really does. Pookie fastens herself to him for neurotic reasons of her own, but she chooses the wrong guy. Jerry is offensively passive, lifeless, colorless, undistinguished. He’ll grow up into the kind of guy who claims he only works here.

Pakula tells their story in two ways. Most of the film is engagingly honest. There’s a sad, funny scene in the motel room as Jerry mechanically undresses Pookie. There’s a good scene in the fraternity house when Pookie gets drunk. A finely acted performance by Tim McIntire, as Jerry’s roommate. And, of course, there’s Miss Minnelli’s justly celebrated telephone scene, during which she begs, pleads and cajoles Jerry in an attempt to salvage their relationship.

This scene is not quite the greatest piece of acting in the history of the movies (although Life magazine would have us believe so), but it is sensitive and good. It is on a level, this year, with Cathy Burns’ monolog in “Last Summer,” and Shirley Knight’s long phone call at the beginning of “The Rain People.” It will probably win Miss Minnelli an Oscar. She works for the largest and most powerful agency in Hollywood, and they’re spending a lot of money hailing it as great art. It is damned good, as I’ve said, but I think they’re overselling it.

In any event, all of these scenes and most of the movie are honest and pretty straight with us. Pakula has a real feel for this relationship and for these two people, and he tells their story well. Where he goes wrong is when he tries to give “The Sterile Cuckoo” the look of a conventional love movie. When he deliberately tries to be contemporary.

We squirm in our seats as the Sandpipers sing “Come Saturday Morning” until you wonder if there aren’t any other days in the week. As I observe here at least twice a month, the Semi-Obligatory Lyrical Interlude has had it as a useful movie device. Every other movie sticks in one of those syrupy Salem ads with the lovers floating over the countryside with the hit single on the sound track.

“Sterile Cuckoo” has not one, nor even two, but no less than three of these insufferable scenes. They seriously interfere with the rhythm of the movie, and they present Pookie and Jerry as conventional lovers — something that is not established in any of the movie’s dramatic scenes.

The result is a schizo directing job. Pakula has a good story, and tells it, and then gums it up with the unnecessary scenes he probably felt obligated to include. So “The Sterile Cuckoo” is not as good as it should have been because it lacks consistency of tone. But parts of it are awfully good, and Miss Minnelli is one hell of an actress.