From time to time you find yourself wondering if there will ever be a movie that understands life the way you’ve experienced it. There are good movies about other people’s lives, but rarely a movie that recalls, if only for a scene or two, the sense and flavor of life the way you remember it.

Adolescence is a period that most people, I imagine, remember rather well. For the first time in your life important things were happening to you; you were growing up; what mattered to you made a difference. For three or four years, every day had a newness and unfamiliarity to it, and you desperately wanted to act in a way that seemed honorable to yourself. Even if you didn’t read Thomas Wolfe you were more idealistic than you were ever likely to be again.

But on top of the desire to be brave and honorable, there was also the compelling desire to be accepted, to be admitted to membership in that adolescent society defined only by those excluded from it. Because you were insecure, like all teenagers still groping for a style and a philosophy, you tended to value other people’s opinions above your own. If everybody else disagreed with you, then how could you be right? And so sometimes you repressed your own feelings, rather than risk being shut out. And yet, inside, there was still the strong force of that idealism, and occasionally it occurred to you that the way you handled these years might decide the worth of your life.

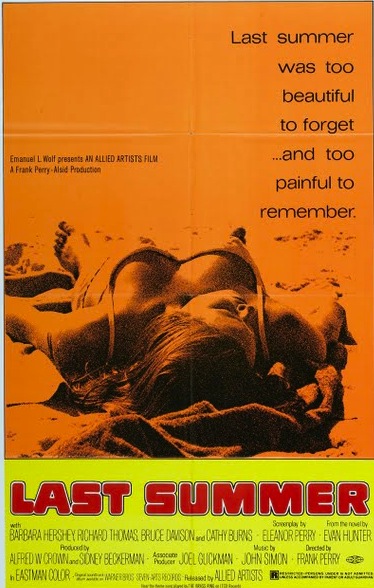

Frank Perry’s “Last Summer” is about exactly such years and days, about exactly that time in the life of four 15- or 16-year-old adolescents, and it is one of the finest, truest, most deeply felt movies in my experience.

As “Last Summer” opens we are introduced to three affluent teenagers, two boys and a girl, who are spending the summer on Fire Island with their parents. Sandy, the girl, is more familiar and experienced with sex than the boys, or so she would have them believe. The two boys are, naturally, unsure of themselves. They are not men and yet must be concerned with manhood. In the hot sun, during the long summer, the three friends circle the knowledge of sex like skittish colts.

But the movie is not really about them. It is about Rhoda, a plump and painfully idealistic girl from Ohio, who is also staying on the island. She forces herself into the group, her loneliness overcoming her shyness. And although she seems the most insecure of them all, she is the only one who knows her own mind and whose decisions are not determined by insecurity.

What happens then — how the story is brought to a conclusion — is not really important to the greatness of the movie. Indeed, the sensational last scene doesn’t strike me as particularly valid. A quieter conclusion would have made the point.

But the movie makes its point anyway, with dialog, with exquisitely drawn characterizations, with a very accurate examination of the adolescent character. Some months ago I attacked a lousy movie, “The First Time,” because it demonstrated no knowledge of how teenagers really talk and think. Godard tells us that the only valid act of film criticism is to make another movie; “Last Summer” will serve as the definitive criticism of “The First Time.”

One scene: Rhoda has just been taught to swim by her friend Peter. They rest on the beach, and she talks about some of the things she believes in, and then he does, and then with infinite delicacy they realize they “like” each other.

Another scene: Sandy and the two boys sit on the beach, drinking beer, fooling around, skirting the awareness of their own new sexuality. During this scene the friends become unequal; Sandy is now in control.

Another scene: A rainy day. Sandy, Peter and Dan experiment with pot. On an impulse, they wash each other’s hair. They talk. They kill time, Rhoda arrives and feels excluded by the camaraderie. They convince her to tell “the worst thing” in her life. Reluctantly, she does; in a brilliantly acted monolog, she describes the death of her mother by drowning. The way Rhoda’s ambiguous feelings are presented makes this the best scene in the film.

There are many other things I want to say about “Last Summer,” but I don’t want to diminish your experience in seeing the film for the first time. So a longer article will have to wait. But let me add that the performances of the four teenagers are the best that could possibly be hoped for; Cathy Burns, as Rhoda, clearly deserves an Academy Award nomination. Barbara Hershey’s character, Sandy, seems easier to play but there is a marvelous subtlety in the way she gradually alters her relationship with the other three. Richard Thomas, as Peter, and Bruce Davison, as Dan, perfectly capture the ambiguity, the self-doubt, of, adolescence.