I am not sure I entirely understand the deer. In “The Ring Two,” Rachel and her young son Aidan visit a farmer’s market. Aidan wanders off and observes some deer that emerge from a nearby forest and stare at him. He stares back.

Later, as mother and son are driving down a little-traveled road, a deer appears in front of their car. “Keep moving,” Aidan says urgently, but his mother hesitates, and soon the car is under attack by a dozen stags, their antlers crashing through the windows. She speeds away and hits another stag, doing considerable damage to her front end.

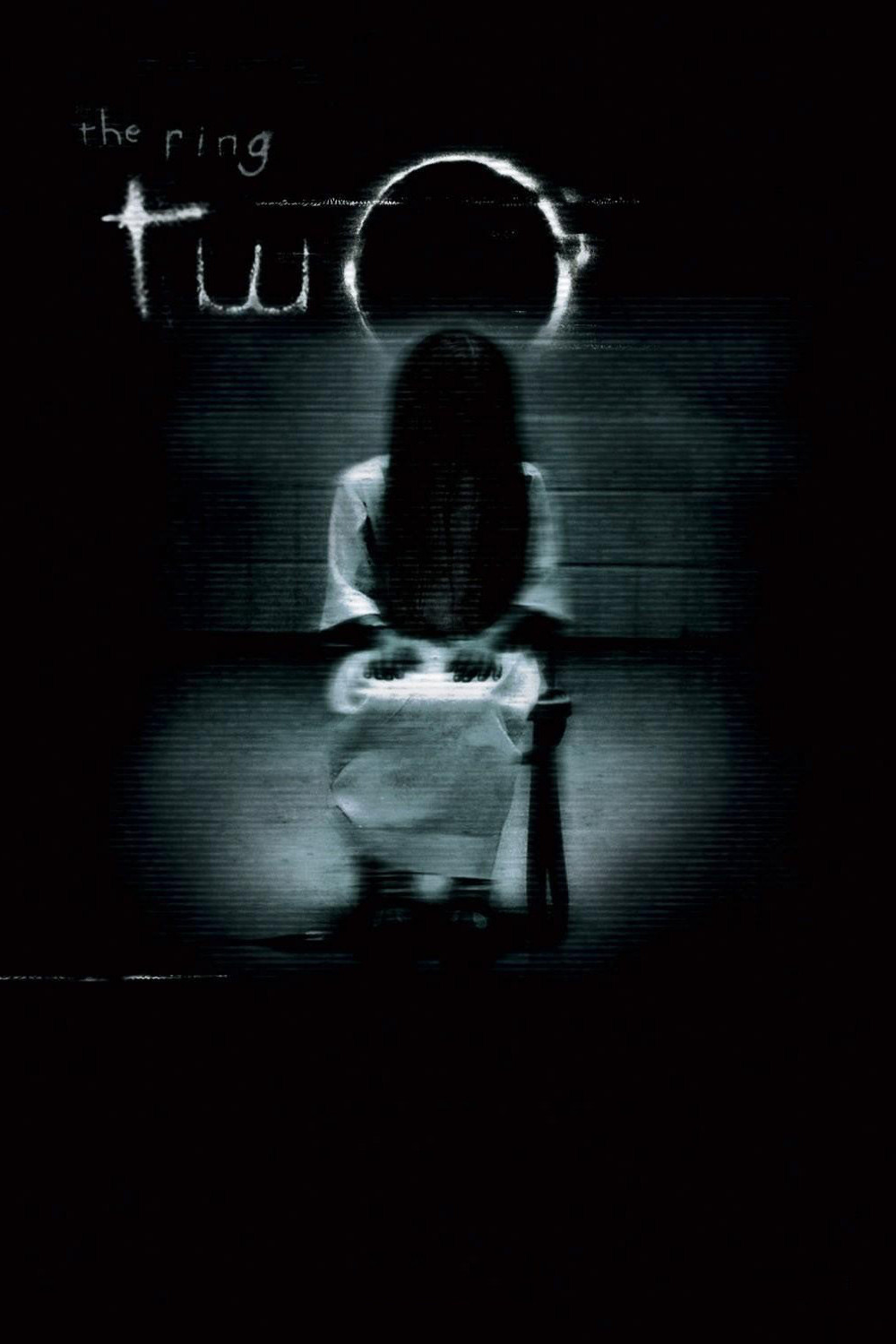

This is in a movie that also involves a mysterious video that brings death to whoever watches it, unless they pass it on to someone else within a week. The video is connected to the death of a young girl named Samara who had a cruel childhood. Samara’s ghost is trying to possess Aidan’s body. Because she died at the bottom of a well, much water is produced wherever her ghost manifests itself. Usually the water is on the floor, but sometimes it flows up to the ceiling.

Rachel visits the old farm where girl was mistreated and died. In the basement, she finds antlers. A whole lot of antlers. So maybe the deer sense Samara’s ghost’s presence in Aidan and are attacking the car in revenge? But Samara was presumably not the deer hunter, being far too occupied as a cruelly mistreated little girl at the time. So is it that the deer are psychic, but not very bright?

One does not know but, oddly, one does not care. The charm of “The Ring Two,” while limited, is real enough; it is based on the film’s ability to make absolutely no sense, while nevertheless generating a real enough feeling of tension a good deal of the time. It is like an exercise in cinema mechanics: Images, music, photography and mood conspire to create a sense of danger, even though at any given moment we cannot possibly explain the rules under which that danger might manifest itself.

We do get some information. Samara, for example, can hear everything Rachel (Naomi Watts) and Aidan (David Dorfman) say to each other, except when Aidan is asleep. So Rachel talks to him a lot while he’s asleep, with dubious utility. They also appear in each other’s dreams, where they either (a) find a loophole by talking to each other while they’re asleep, or (b) are only dreaming.

Meanwhile, the video gimmick, which supported “The Ring” (2002), is retired and the action centers on Samara’s assaults on Aidan’s body and Rachel’s attempts to defend him. At one point this involves almost drowning him in a bathtub, which is the second time in a month (after “Constantine“) that being almost drowned in a bathtub is employed as a weapon against supernatural forces.

The movie has been directed by Hideo Nakata, who directed the two famous Japanese horror films “Ringu” (1998) and “Ringu 2” (1999), although “The Ring Two” is not a remake of “Ringu 2.” It is a new departure, as Rachel, a newspaper reporter, leaves Seattle and gets a job on the paper in the pretty but rainy coastal town of Astoria, Ore. Here perhaps the tape and its associated menace will not follow them.

Naomi Watts and David Dorfman are always convincing, sometimes very effective, in their roles; in the scene where she’s going down into the basement, we keep repeating, “it’s only a basement,” but I was surprised that the ancient cinematic techniques still worked for me. In all such scenes it is essential for the camera to back into the basement while focused on the heroine, so that we cannot see what she sees, and therefore, through curious movie logic, neither can she.

The scenes involving Aidan’s health are also well handled, as his body temperature goes up and down like an applause meter, reflecting the current state of Samara’s success in taking over his body. If he becomes entirely a ghost, does he go down to room temperature? Elizabeth Perkins plays a psychiatrist who thinks Aidan may have been abused, and there is a creepy cameo by Sissy Spacek, wearing scary old lady makeup, as Samara’s birth mother. Aidan always calls his mother “Rachel,” by the way, and when he starts calling her “Mommy,” this is not a good sign.

When I say the film defies explanation, that doesn’t mean it discourages it. Web sites exist for no other reason than to do the work of the screenwriters by figuring out what it all means. For example, when Rachel rolls the heavy stone across the top of the well, does that mean Samara is out of business? Rachel seems to think so, but wasn’t the stone always on top of the well?