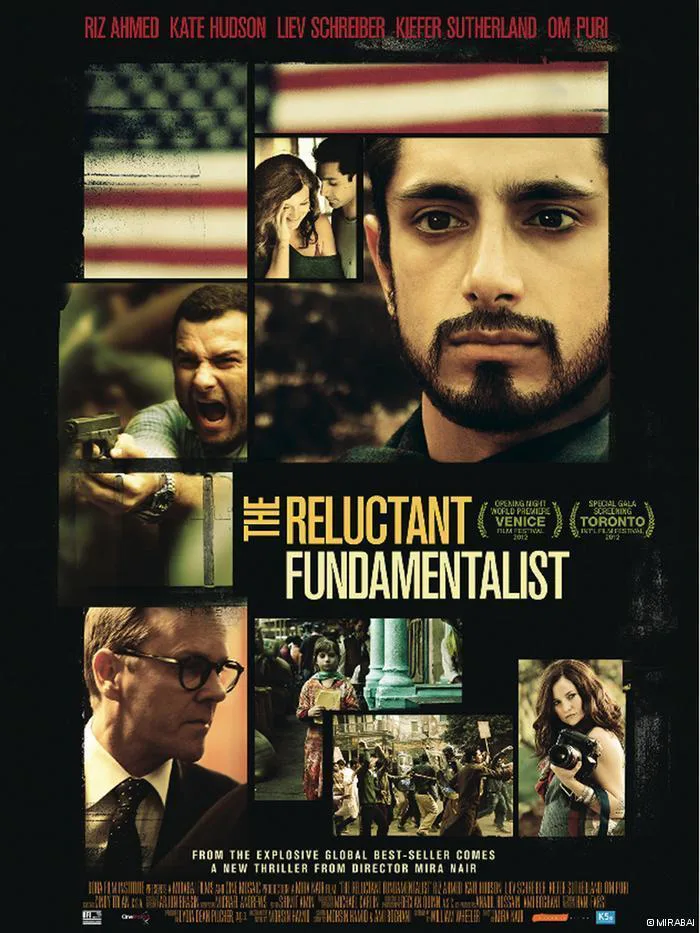

Mira Nair‘s “The Reluctant Fundamentalist” follows the transformations of the wide-eyed Pakistani Changez Khan (Riz Ahmed), who arrives in the US with great professional ambitions. And he accomplishes much before the planes hit the World Trade Center, a crisis that challenges his materialism, leading him to step back from the many choices he’s made, in his capitalist career and his love life.

He narrates his story, seen in flashback, while meeting in the Pak Tea House in Lahore with American journalist Bobby Lincoln (Liev Schreiber). Quite bulky for a journalist, with something strange in his posture, Lincoln seems out of place. A local American professor has just been kidnapped. Khan, who has long since abandoned his clean-shaven face and American business suit for a beard and traditional Shalvar-Kameez, is now the leader of a questionable Pakistani activist movement. Lincoln thinks he might have some answers, but Khan insists on telling his own life story first. The choice seems odd, considering that a man’s life is in danger.

The first part of his biography is all too familiar. A poor immigrant from a colorful family abandons his roots to dive head first into the American Dream. He stumbles into love with sullen artist Erica (Kate Hudson), coping with the loss of her previous boyfriend. He seizes a major corporate job under the stern tutelage of Jim Cross (Kiefer Sutherland). Khan outshines his colleagues with a combination of aggression and brilliance. Including some unnecessary coincidences, we have seen this first act before in many other movies.

Then, however, things change. After a long business day in Southeast Asia, Khan sits in a dark, quiet hotel room. He turns on the television. The second plane hits the towers. The trailer for “The Reluctant Fundamentalist” shows post-9/11 America as a land of war, triumphalism, and bigotry. But that’s not what happens in the film itself. Yes, Khan is humiliated by every type of law enforcement. Customs officials strip search him. Police officers arrest him for being the wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time. FBI agents get in his face (meaning, they virtually stare into the camera) and accuse him of assorted terrorist schemes.

And yes, in the immediate moments after the attacks, his co-workers spew bits of anti-Muslim hatred, but not aimed at him. For everyone in his world, life goes on and he remains a vital part of their professional and personal lives.

But Khan’s challenge comes less from without and more from within. He questions his identity, while his conscience struggles with his ethical choices. He is a Third World man rising to the heights of an imperialist nation. As an American, he benefits from our foreign interventions exploiting his “own people.” Further, he contributes to the problem: In arranging mergers and acquisitions, he himself drives thousands of people into unemployment. They expectedly lash back at him, recalling in a small way insurgents retaliating against occupiers. After a few conversations with clients about the histories of Western and Muslim empires, perhaps compounded by unspoken reflections on his own name — Changez is an Urdu variation of Genghis — Khan drops everything and heads home.

It is worth noting that Khan, returning to the Subcontinent, does not abandon America. He goes back to his roots in Lahore, but he is now a different person, embracing a different world. He becomes a third man, a hybrid of the Pakistani poet’s son and the New York businessman. Now a professor, he spends hours in this same tea shop, with his many loyal students. The Pak Tea House is a real location whose clients were among the Indian Subcontinent’s greatest thinkers and poets. But to Bobby Lincoln, Khan is a dissident with links to terrorists maneuvering to replace al-Qaida.

William Wheeler adapted his screenplay from Mohsin Hamid’s best-selling novel and its central clash between tradition and progress, old and new, recalls Nair’s “Mississippi Masala” (1991). As that story concluded, each conversation seemed to find multiple dimensions, each character seemed to have a second story. Here, as the story unfolds, new dimensions change our perceptions of the central characters, sometimes for better, and occasionally for worse. The point is that every character and every setting has at least two sides.

Riz Ahmed’s subtle transformations carry the film. The other characters have their own attributes, but their roles are limited. Schreiber, Sutherland, Hudson, Om Puri and Shabana Azmi exhibit only a couple specific expressions each, and do so repeatedly. Declan Quinn’s cinematography, however, fills the screen with rich shades and thick colors. Nair has made a very smart film, whose ambitions sometimes exceed the piece’s depths.

“The world changed on 9/11” was a phrase we used to hear all the time. The film left me wondering how many of us were compelled to re-evaluate our own individual paths or modify our moral and political priorities during the long wars in the years that followed. Is Khan the exception? For the rest of us, then and now, as things around us get more nasty and complicated, life goes on.