The director Mira Nair made an unexpected discovery a few years ago: A lot of the independent motels in the Deep South are owned and operated by Asian Indians. Although they trace their roots back to India or Pakistan, many of them arrived in America via Uganda, where they had put down roots for two or three generations, showing a gift for running small businesses before Idi Amin ordered them all to leave in 1972. Nair, who is herself from India via Harvard, made her discovery while journeying in the South after the release of “Salaam Bombay!” (1988), her wonderful first film about a street child. She decided to make a movie about it.

Her new film opens in Uganda, where an Indian lawyer’s family lives in comfort and security until Amin confiscates the property of tens of thousands of Indians and orders them to leave immediately. The story continues in Greenwood, Miss., where the lawyer and his wife (Roshan Seth and Sharmila Tagore) own a shabby roadside motel. Their daughter Mina (Sarita Choudhury), a child with sketchy memories of Africa, has grown into a ripe beauty of 24, with an American accent that immediately suggests she does not share all of her family’s ideas.

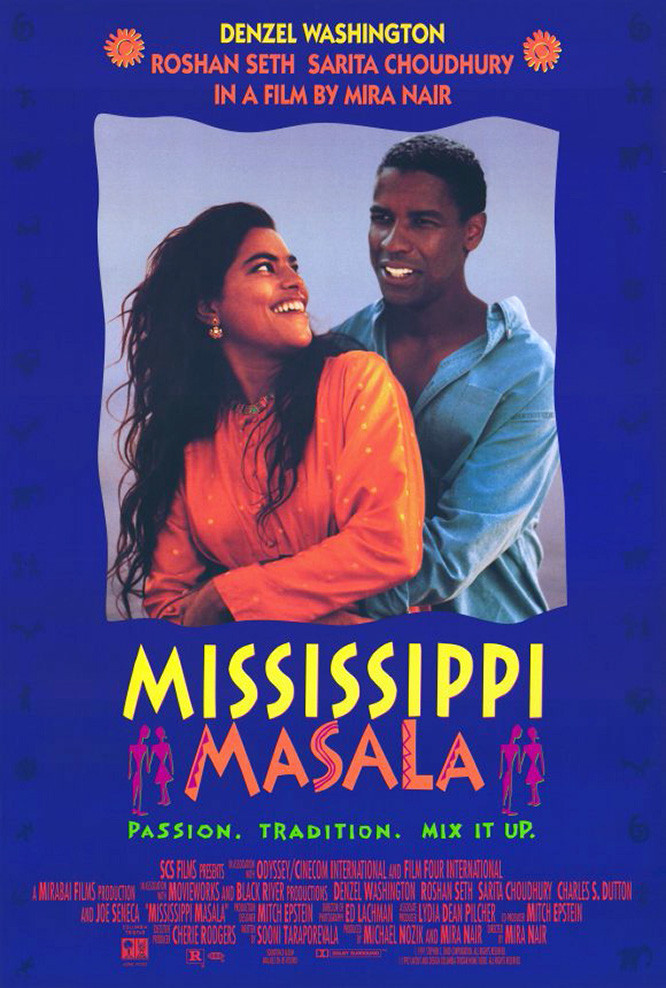

Driving a car one day, she crashes into the van of a young black man (Denzel Washington), and exchanges addresses and perhaps a subtle glance of curiosity. He’s interested too, and eventually they go out on a date. This is not the sort of social life Mina’s parents approve of; they expect their daughter to marry within their extended community of Indian exiles, and forbid her to see Washington.

The ban only serves to underline the isolated nature of the young woman’s life, and there are ironies in the racism and color consciousness she faces. Within her own community, she is considered too dark-skinned to make a desirable wife (her mother explains that if you want to catch a husband, you can be dark and rich, or light and poor, but not dark and poor). Within the black community, the Indian woman is at first accepted with friendliness (Washington takes her to meet his family at a backyard picnic). But after all of the local Indian motel owners boycott Washington’s rug-cleaning company, the blacks get angry, too.

What we are dealing with is more than a transplanted version of “Romeo and Juliet.” Both the black and Indian characters (and certainly the local whites, who are not much of a factor in this movie) have a vast and comfortable lack of curiosity about other races; they prefer to think of them in stereotypes, and have no desire to meet them as individuals. When the Indian woman and the black man meet and fall in love, everyone on all sides falls obediently into place to condemn their relationship.

It was racism, of course, that brought the Indians to Africa in the first place, to build the railroads, and racism that kicked them out. And it was racism that brought Africans to America. But to be a victim of the racism of others does not inoculate anyone against the prejudice that can grow in their own hearts.

All of these serious questions linger just under the surface of “Mississippi Masala,” which is, despite its subject, surprisingly funny and cheerful at times, and generates a full-blown romanticism.

Denzel Washington is an actor of immense and natural charm, and he makes a good match with Sarita Choudhury, a newcomer who seems a little awkward in some of her scenes, but uses that feeling as part of her performance.

If I have a complaint about Nair’s work, it’s that she tries to cover too much ground. She knows a lot about her subject, but should have decided what was important and left out the rest. The scenes in Uganda, for example, are not necessary for narrative purposes, and her closing scenes (as the father returns to the home of 20 years earlier) upstages the conclusion of the love story.

She also has a lot of material about the daily lives of Indians in Mississippi, and while I find some of it amusing and all of it interesting, it also serves to keep the young lovers out of the foreground for extended periods of screen time.

There are really three movies here: the exile from Uganda, the love story, the lives of Indians in the Deep South, and really only screen time enough for one of them.

And yet I do not complain too much, because “Mississippi Masala” has the benefit of showing me people I had not met before, coping with the human currents that carried them all, blacks and Indians, out of Africa and across the ocean to Mississippi. The movie is about people who, having survived those upheavals, nevertheless have no curiosity about those outside their own social and racial circles – and about a few who do.