“The Power of One” begins with a canvas that involves all of the modern South African dilemma, and ends as a boxing movie. Somewhere in between, it loses its way. The film, which spans the years surrounding the Second World War, tells the story of a young English-speaking boy who is sent to an Afrikaanslanguage boarding school, where a neo-Nazi clique makes his life miserable. He fights back, and keeps fighting back when, as a young man, he becomes friends with Africans who are part of a developing political movement.

His story was first told in a thoughtful historical best seller by Bryce Courtenay, who tried to give some sense of what it was like to grow up as an English-speaking liberal in a country where apartheid and aspects of the police state were combined in an unholy marriage with parliamentary democracy. In a sense, the story of “The Power of One” could continue right down to the March 17 referendum in which a majority of South Africa’s white voters ratified de Klerk’s decision to move toward black majority rule. That would be the happy ending.

But “The Power of One” wants to be more than the story of a young man whose life reflects the times of his country. It also wants to be a box office hit, and in playing the notes of mass entertainment, it loses its purpose. You can almost feel the film slipping out of the hands of its director, John G. Avildsen, as the South African reality is upstaged by the standard cliches of a fight picture.

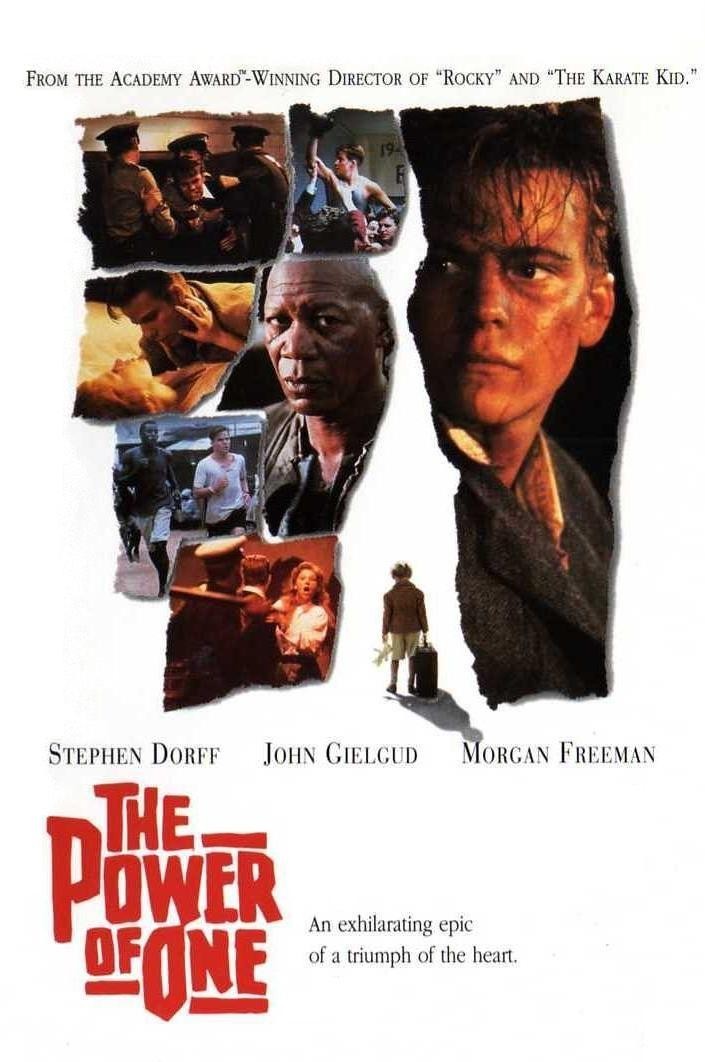

The hero, nicknamed P.K., is played by Stephen Dorff as a perpetual outsider who is victimized at an Afrikaans boarding school by young students whose idol, in the years before World War Two, is Hitler. They stage secret meetings and mock trials, kill his beloved pet chicken, and are ready to humiliate the boy in a bizarre ceremony before the authorities finally step in. These scenes are meant to show the lasting antagonism between the two white tribes of South Africa, the Afrikaaners and the British, although in reality, given the poverty and powerlessness of most Afrikaaners in the 1930s, it would have been much more likely (if less tidy) to show an Afrikaaner boy taunted at an English boarding school.

The little neo-Nazis are led by a punk with a swastika tattooed on his arm, and at the point where that same tattooed arm turns up attached to a bullying officer of the state security force, I knew the movie was lost. “The Power of One” makes the same crucial error as “Article 99”; it diminishes evil by embodying it in one man who must be vanquished. By implying that his defeat is the defeat of his system, it avoids the real issues. (Indeed, this movie ends before the worst of apartheid is even enacted into law.) P.K. is embraced in the movie by young blacks who form the core of a new political movement. They see him as a symbol, as a myth (these are their own words) who, as a boxing champion, can help lead them to freedom. P.K. becomes best friends with a young African man, also a boxer, and as they climb into the ring with one another (in an unsanctioned interracial fight), the African cheerfully explains that whoever wins, a leader will be born.

This is pretty shaky politically. And it continues the tendency of so many recent films about South Africa, like “Cry Freedom,” to embody the anti-apartheid struggle in an heroic white man, presumably so white Western audi ences will have an easier time identifying.

The film, shot in Zimbabwe, begins with a clear sense of the land and the attachment of all Southern Africans to it. It shows the symbiotic, if paternalistic, relationship of blacks and whites in rural areas. It gives some sense of the beginnings of apartheid. But then it turns into another movie about a bad bully, and by the end, when the hero and the neo-Nazi are mano-a-mano, and riots are sweeping Alexandria township, I was in despair. South Africa is too complex to be reduced to a formula in which everything depends on who shoots who.

There are some nice touches: John Gielgud as a headmaster, happy in his academic ivory tower in the midst of upheaval; the brightness and energy of the soundtrack, largely recorded by Bulowayo choral groups; the very proper, venomous racism expressed at the dining table of a government minister; the photography of the heartbreakingly evocative landscape. But how can you forgive a movie that begins by asking you to care who will win freedom, and ends by asking you to care who will win a fight?