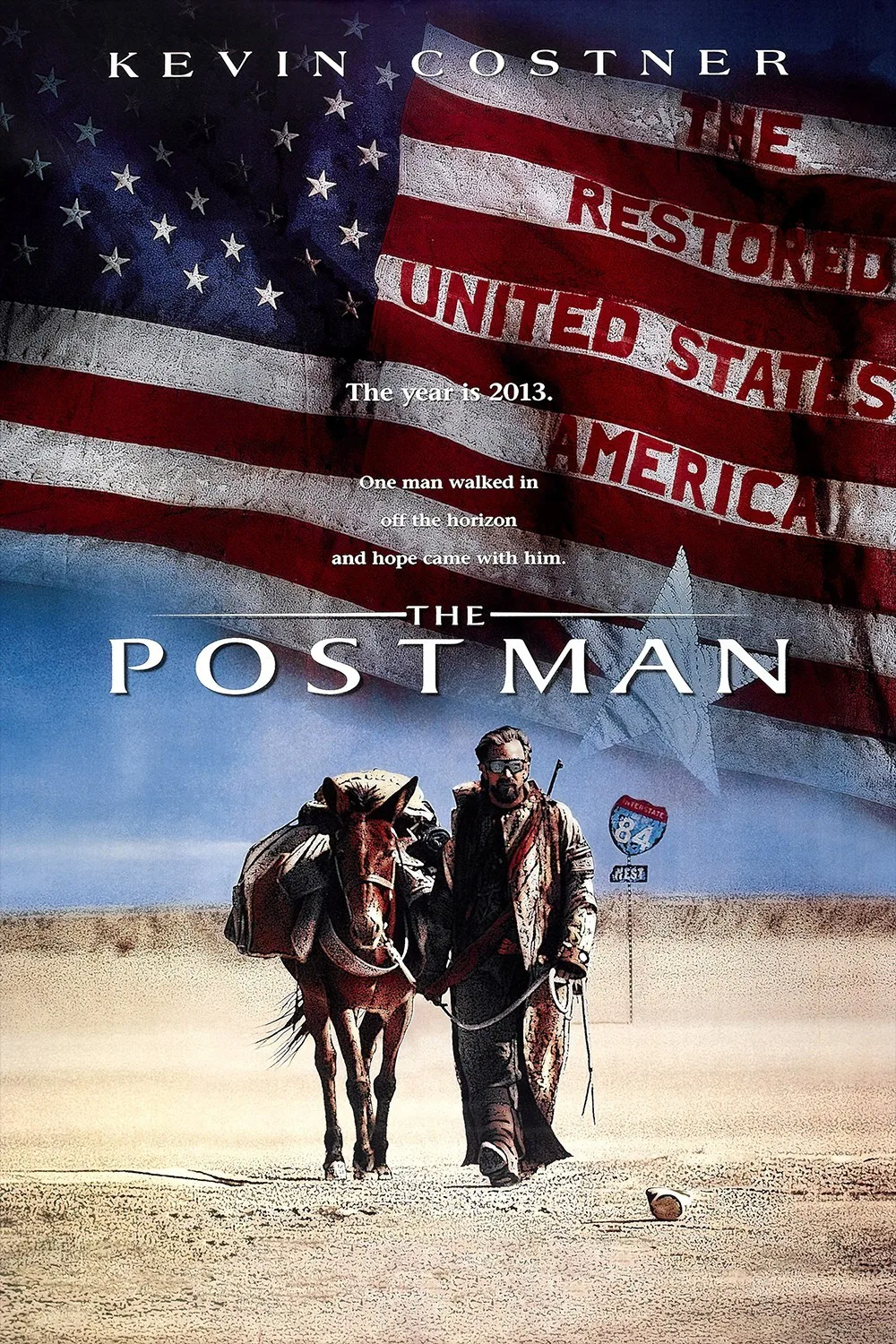

There are those who will no doubt call “The Postman” the worst film of the year, but it’s too good-hearted for that. It’s goofy, yes, and pretentious, and Kevin Costner puts himself in situations that get snickers. And it’s way too long. But parables like this require their makers to burn their bridges and leave common sense behind: Either they work (as “Forrest Gump” did), in which case everyone involved is a genius, or they don’t–in which case you shouldn’t blame them for trying.

In choosing “The Postman” as his new project, however, Costner should perhaps have reflected that audiences were becoming overfamiliar with him as the eccentric loner in the wilderness who discovers an isolated community and then joins their war against evil marauders. He told that story magnificently in “Dances with Wolves” (1990) and then did another version in the futuristic fantasy “Waterworld” (1995). Now he sort of combines them, in a film that takes place in the post-Apocalyptic future like “Waterworld,” but looks and feels like it takes place in a Western.

The movie, based on an award-winning science fiction novel by David Brin, takes place in 2013. The dust clouds have settled after nuclear war, and scattered communities pick up the reins of civilization. There is no central government. Costner is a lone figure in the wilderness, friendly only with his mule, named Bill. They support themselves by doing Shakespeare for bands of settlers. Bill can hold a sword in his mouth, and in “Macbeth” he plays Birnam Wood. His master recites lines like, “Life is a tale told by a moron,” not the sort of mistake he’d be likely to make, especially with a woman helpfully prompting him by whispering, “Idiot! Idiot!” Or maybe she’s a critic.

Costner is conscripted into a neofascist army run by Gen. Bethlehem (Will Patton). He escapes, stumbles over an abandoned U.S. Mail van and steals the uniform, cap and letterbag of the skeleton inside. At the gates of a settlement called Pineview, he claims he has come to deliver the mail. Building on his fiction, he tells the residents of a restored U.S. government in Minneapolis. The sheriff spots him for a fraud, but the people want to believe, and the next morning, he finds letters pushed under his door. Walking outside, he discovers that all the townspeople have gathered in hushed silence in a semicircle around his lodging, to await his awakening and appearance–the sort of thing that happens in movies, but never in real life, where some helpful townsman invariably suggests, “Let’s just wake the sonuvabitch up.” In a movie that proceeds with glacial deliberation, the Postman becomes a symbol for the survivors in their struggling communities. “You give out hope like it was candy in your pocket,” a young woman tells him. It’s the sort of line an actor-director ought to be wary of applying to his own character, but Costner frankly sees the Postman as a messiah, and there is a shot late in the film where he zooms high above a river gorge in a cable car that serves absolutely no purpose except to allow him to pose as the masthead on the ship of state.

That young woman (Olivia Williams), by the way, wants the Postman’s semen. Her husband is infertile after the “bad mumps,” and the couple desires a child. The Postman eventually obliges, and she makes love with him in a scene reminiscent of those good Victorian wives who closed their eyes and thought of the empire. Her husband is murdered, and she’s kidnapped by Gen. Bethlehem, who has seen “Braveheart” and knows about the feudal system where the lord gets first dibs on the wedding nights of his vassals. She and the Postman eventually escape into the wilderness and spend the winter together while she comes full term. This is some frontier woman; in the spring, she burns down their cottage so they’ll be forced to move on, and “we can find someplace nice for the baby.” In his absence, the Postman’s legendary status has been magnified by young Ford Lincoln Mercury (Larenz Tate), who has named himself after an auto dealership and in the absence of the Postman has organized a postal service in exile. It is clear that the Postman and Bethlehem will sooner or later have to face each other in battle. When they do, the General produces a hostage he has captured–Ford L. Mercury–and the Postman pales and pauses at the prospect of F.L. Mercury’s death, even though the Postman’s army consists mostly of hundreds of women and children he is cheerfully contemplating leading to their slaughter.

The movie has a lot of unwise shots resulting in bad laughs, none more ill-advised than one where the Postman, galloping down a country lane, passes a gate where a tow-headed little tyke holds on a letter. Some sixth sense causes the Postman to look back, see the kid, turn around, then gallop back to him, snatching up the letter at full tilt. This touching scene, shot with a zoom lens in slow motion to make it even more fatuous than it needed to be, is later immortalized in a bronze statue, unveiled at the end of the movie. As a civic figure makes a speech in front of the statue, which is still covered by a tarpaulin, a member of the audience whispered, “They’ve bronzed the Postman!” Dear reader, that member was me, and I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised that I was right.