“Reality: What does it mean?” Curtis Mayfield asked in one of his most provocative songs. (Okay, it was just “Freddie’s Dead,” great tune but not THAT provocative.) The answer to the question is up for grabs every day.

The actor Mark Webber, who you may recall in ingratiating comic turns in movies such as “Scott Pilgrim vs. The World” and more intense dramatic portrayals in movies such as “The Hottest State,” has been directing films since 2008, and from his second feature, 2012’s “The End of Love,” has been working in a mode he calls “reality cinema.” Which may suggest this question: “’Reality cinema’: What does it mean?”

Webber explained it to the site No Film School last year: “I thought, ‘Why don’t I create an environment that’s totally different, that allows us to completely inhabit these characters around real-life situations?’ And maybe, just maybe, I’ll be able to really get real vérité on the screen. I wanted to show real emotions and real vulnerability. The type of movies that I respond to are the ones where I watch them and I’m like, ‘Something different is happening.’ I’m trying to do that by injecting a lot more truth into the storytelling process.”

What it means in practical terms has been that actors appear in his films as themselves, or at least playing characters whose names they share. And while the precipitating incident or situation that propels the narrative is fictional, their reactions and interactions are authentic, or “authentic.”

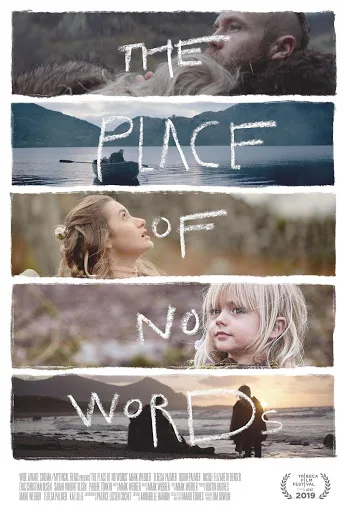

With 2014’s “The Ever After” and now this film, “The Place of No Words,” Webber centers the work around his family. That means wife Teresa Palmer, and in this film, their three-year-old son Bodhi Palmer. The situation being faced is a grave one.

This movie has a startling opening. It captures a young boy and an adult in a contemporary bedroom, having a conversation that features a good deal of nonsense words, and aside from the super-wide aspect ratio of the frame, looks pretty much exactly like any generic indie family drama you’d care to invoke. But there’s a sudden cut, to an epic view of a wide open sea, and a wide, long, rowboat. The man, played by Webber, now has a thick long beard (his hair and beard stylings in this movie are a lot, and I mean that literally) and is furiously hoisting oars as the child sits facing him while the sea roils noisily. Subsequent gorgeous shots suggest a Viking epic. (The cinematographer is Patrice Lucien Cochet, who contributes inspired work throughout.) As do the characters’ costumes: fur capes, elaborate leather boots, and swords. Soon as this pair reached land, they start climbing a mountain. Looks like maybe they’re headed to a photo shoot for a Led Zeppelin reunion album.

There are, we come to learn after this disorienting change of setting, two discrete narratives in this movie that intertwine the same theme. The one in which Bodhi and Mark trudge around in a fantasy realm, and meet fairies, and navigate a swamp that farts (really), is the fantasy world concocted by Bodhi. Hence the farting swamp, with mud, or “mud,” that’s actually chocolate, a concept befitting a three-year-old. In the real world, Mark is fatally ill, and not likely to live to see Bodhi’s next birthday. But the philosophical discussions about Mark’s condition are most fruitfully carried out within the fantasy realm.

In the everyday world of stiff-upper-lip social gatherings and hospital beds, things are a little more banal, and immediately painful. Philosophical considerations are difficult to articulate in the environment of pain the characters inhabit.

For a lot of viewers the premise will be a substantial turn-off. An artist imagining their own death is traditionally a sort of apex of indulgent self-involvement. While Webber’s depictions of illness are notably lacking in bathos, that won’t make the concept less of a deal-breaker for skeptics. But the movie’s imaginative energy is undeniable, and Bodhi himself is a winning screen presence. If Webber sticks to his creative guns, he could well become the John Cassavetes of attentive (albeit eccentric) parenting.