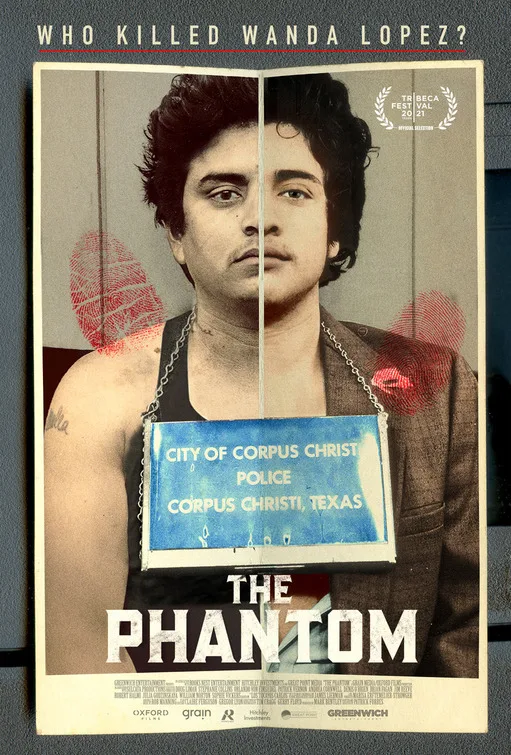

It seemed like justice. The first third of “The Phantom,” a documentary about the exoneration of a man executed in 1989 for a murder committed by someone else, might even convince you that Carlos DeLuna deserved to be found guilty for the murder of a young cashier named Wanda Lopez. DeLuna, then 20 years old, was arrested near the scene, hiding from the police with cash in his pocket that almost matched the amount stolen. He was identified by witnesses. He had a record of getting into trouble. His brother had all but given up on him after DeLuna stole his truck and took their mother’s money. And DeLuna did not do much to defend himself.

His alibi was “clearly a lie.” It wasn’t until the trial was underway that he revealed the name of the man he said committed the murder: Carlos Hernandez. In that part of Texas, he might as well say John Smith. But the police looked into all of the Carlos Hernandezes who had been arrested in the area in the past ten years. None of them did it. The prosecutor called DeLuna a “predator,” warning the jury, “He will harm again.” Determinations of guilt are based on reasonable doubt, not absolute certainty. Finding DeLuna guilty seems reasonable.

However, there were already indications that there was more than a reasonable doubt. Lopez was stabbed to death with a knife and photos of the scene show a lot of blood. But DeLuna had no blood on his clothes or shoes. While DeLuna had been in trouble before, stabbing a woman to death “was not his manner of committing crimes.” One commenter says, “the only evidence is eyewitness evidence, and that’s the worst evidence in the world.”

Some of the people from the community say that in cases where the victim and/or the accused are Latinx, the system does not try as hard to find the truth. And, as the reporter who followed the case on one of her first assignments says, “there’s not always two sides to a story; sometimes there are three, four, or five.”

The first part of “The Phantom” could almost be a summation to the jury by the prosecution. But then we get the other sides to the story, and the story as presented to us so far begins to unravel. Those eye-witnesses? “It was dark and they had a guy in the car,” one of them says now. The man they saw wore a white shirt. The man in the car was shirtless. “I probably should have asked, ‘Where is his shirt?'” Sometimes we see what we want to see, especially when it comes to our need to find a resolution that feels comfortable and, well, resolved. Culprit behind bars; all is well.

The storytelling is not as compelling as in other documentaries about exoneration or the death penalty, like “The Thin Blue Line” or “At the Death House Door” (whose unforgettable central character, former Death Row chaplain Carroll Pickett, provides a heartfelt conclusion here). The film’s re-enactments are not as effective as they try to be, and some less important details are given more attention than they deserve.

And here is where the most controversial idea of the moment enters the story. No one mentions it explicitly in the movie, but this film could be in the curriculum of a grad school course on Critical Race Theory, which is not, as some confused people claim, about diversity training in corporate offices or amending history books in grade school. It’s about academic research into the ways our legal system perpetuates injustice along racial lines instead of fighting it.

That is where the film takes us next, not to a bunch of theoreticians in an ivory tower but to Columbia Law School, where professor James Liebman was writing about the death penalty in Texas. As archival footage shows, then-Governor George W. Bush insisted that every person executed was guilty after a fair trial. As Liebman’s research showed on error rates in capital cases, that was not true. So he looked for an example and found DeLuna. Liebman and his students dug into every detail of the case, even hiring a private detective. As he wrote, “Everything that could go wrong in a criminal case did.” “Phantom” refers to “things that didn’t get discovered before.” That happens far more often when the defendant (and in this case, the victim) are poor and/or people of color.

The main takeaway here is not that one man was executed for a crime he did not commit, nor is it the equally disturbing failure of law enforcement to pursue extensive evidence that the Carlos Hernandez DeLuna named as the killer was stabbing and raping women and killing at least one other. The central question concerns how many other Carlos DeLunas and victims of people like Carlos Hernandez there are in the system, and what we have to do to make sure they get the same opportunity for justice as the wealthy and powerful.

Now playing in select theaters and available on digital platforms.